The Wrong of Explicit Simulated Depictions

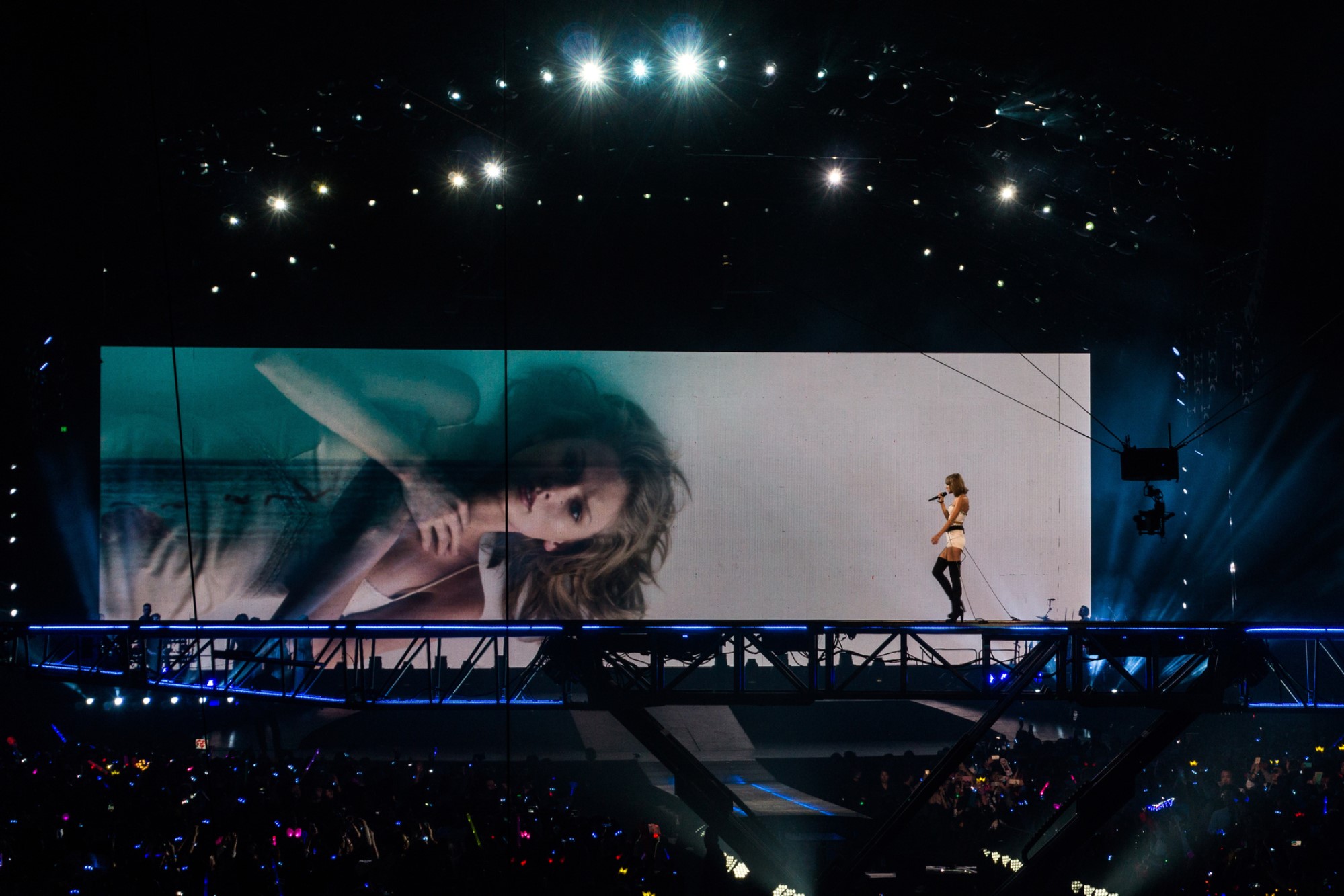

In late January, images began circulating on social media that appeared to be sexually explicit images of pop star Taylor Swift. One particular post on X (i.e., Twitter) reached 47 million views before it was deleted. However, the images were, in fact, fake. The products of generative AI to be specific. Recent reporting traces the origin of the images to a thread on the online forum 4chan, wherein users “played a game” which involved utilizing generative AI to create violent and/or sexual images of female celebrities.

This incident has drawn renewed public attention to another potentially negative use of AI, prompting action on the part of legislators. H.R. 6943, the “No AI Fraud Act”, introduced in January albeit before the Swift incident, if passed, would hold individuals who distribute or create simulated likenesses of an individual or their voice liable for damages. EU Negotiators agreed on a bill that would criminalize sharing explicit simulated content. The Utah State legislature has introduced a bill, expanding previous legislation, to outlaw sharing AI-generated sexually explicit images.

There is certainly much to find disturbing about the ability of AI to create these fakes. However, it is worth carefully considering how and why explicit fakes are harmful to those depicted. Developing a clear explanation for why such images are harmful (and what makes some images more harmful than others) goes some way toward determining how we ought to respond to the creators and distributors. Intuitively, it seems that the more significant harm is, the more appropriate a greater punishment would be.

For the purposes of this discussion, I will refer to content that is created by an AI as a “fake” or a “simulation.” AI generated content that depicts the subject in a sexualized manner will be referred to as an “explicit fake” or “explicit simulation.”

Often, the worry about simulated likenesses of people deals with the potential for deception. Recently, in New Hampshire, a series of robocalls utilizing an AI generated voice mimicking President Joe Biden instructed Democrats to not vote in the upcoming primary election. An employee of a multinational corporation transferred $26 million to a scammer after a video call with AI generated videos resembling their co-workers. The examples go on. Regardless, each of these cases are morally troubling because they involve using AI deceptively for personal or political gain.

However, it is unclear that we can apply the same rationale to explicit fakes. They may be generated purely for the sake of sexual satisfaction rather than material or competitive gains. As a result, the potential for ill-gotten personal and political gains are not as high. Further, they may not necessarily require deception or trickery to achieve their end (more on this later, though). So, what precisely is morally wrong with creating and sharing explicit simulations?

In an earlier analysis, Kiara Goodwine notes that one ethical objection to explicit simulations is that they depict a person’s likeness without their consent. Goodwine is right. However, it seems that there is more wrong here than this. If it were merely a matter of depicting someone’s likeness, particularly their unclothed likeness, without their consent, then imagining someone naked for the purposes of sexual gratification would be as wrong as creating an explicit fake. I am uncertain of the morality of imagining others in sexual situations for the sake of personal gratification. Having never reflected seriously on the morality of the practice, I am open to being convinced that it is wrong. Nonetheless, even if imagining another sexually without their consent is wrong, it is surely less wrong than creating or distributing an explicit fake. Thus, we must find further factors that differentiate AI creations from private mental images.

Perhaps the word “private” does significant work here. When one imagines another in a sexualized way without their consent, one cannot share that image with others. Yet, as we saw with the depiction of Swift, images posted on the internet may be easily and widely shared. Thus, a crucial component of what makes explicit fakes harmful is their publicity or at least their potential for publicity. Of course, simulations are not the only potentially public forms of content. Compare an explicit fake to, say, a painting that depicts the subject nude. Both may violate the subject’s consent and both have the potential for publicity. Nonetheless, even if both are wrong, the explicit deepfake seems in some way worse than the painting. So, there must be an additional factor contributing to the wrongs of explicit simulations.

What makes a painting different from the AI created image is its believability. When one observes a painting or other human created work, one recognizes that it depicts something which may or may not have occurred. Perhaps the subject sat down for the creator and allowed them to depict the event. Or perhaps it was purely fabricated by the author. Yet what appear to be videos, photos or recorded audio seem different. They strike us with an air of authenticity or believability. You need pics or it didn’t happen. When explicit content is presented in these forms, it is much easier for the viewers to believe that it does indeed depict real events. Note that viewers are not required to believe the depictions are real for them to achieve their purpose, unlike in the deception cases earlier. Nonetheless, the likelihood that viewers believe the veracity of an explicit simulation is significantly higher than with other explicit depictions like painting.

So, explicit fakes seem to generate harms due to a triangulation of three factors. First, those depicted did not consent. Second, explicit fakes are often shared publicly or at least may easily be shared. Third and finally, they seem worse than other false sexualized depictions because they are more believable. These are the reasons why explicit fakes are harmful but what precisely is the nature of the harm?

The harms may come in two forms. First, explicit simulations may create material harms. As we see with Swift, those depicted in explicit fakes are often celebrities. A significant portion of a celebrity’s appeal depends on their brand; they cultivate a particular audience based on the content they produce and their public behavior, among other factors. Explicit fakes threaten a celebrity’s career by damaging their brand. For instance, someone who makes a career by creating content that derives its appeal, in part, from its inoffensive nature may see their career suffer as a result of public, believable simulations depicting them in a sexualized fashion. Indeed, the No AI Fraud act stipulates that victims ought to be compensated for the material harms that fakes have caused for their career earnings. Furthermore, even for a non-celebrity, explicit fakes can be damaging. They could place one in a position where they have to explain away fraudulent sexualized images of them to an employer, a partner or a family member. Even if one understands that the images are not real, it may nonetheless bias their judgment against the person depicted.

However, explicit fakes still produce harms even if material consequences do not come to bear. The harm takes the form of disrespect. Ultimately, by ignoring the consent of the parties depicted, those who create and distribute explicit fakes are failing to acknowledge the depicted as agents whose decisions about their body ought to be respected. To generate and distribute these images seems to reduce the person depicted to a sexual object whose purpose is strictly to gratify the desires of those viewing the image. Even if no larger harms are produced, the mere willingness to engage in the practice speaks volumes about one’s attitudes towards the subjects of explicit fakes.