CRISPR is in the news again! And, again, I don’t really know what’s going on.

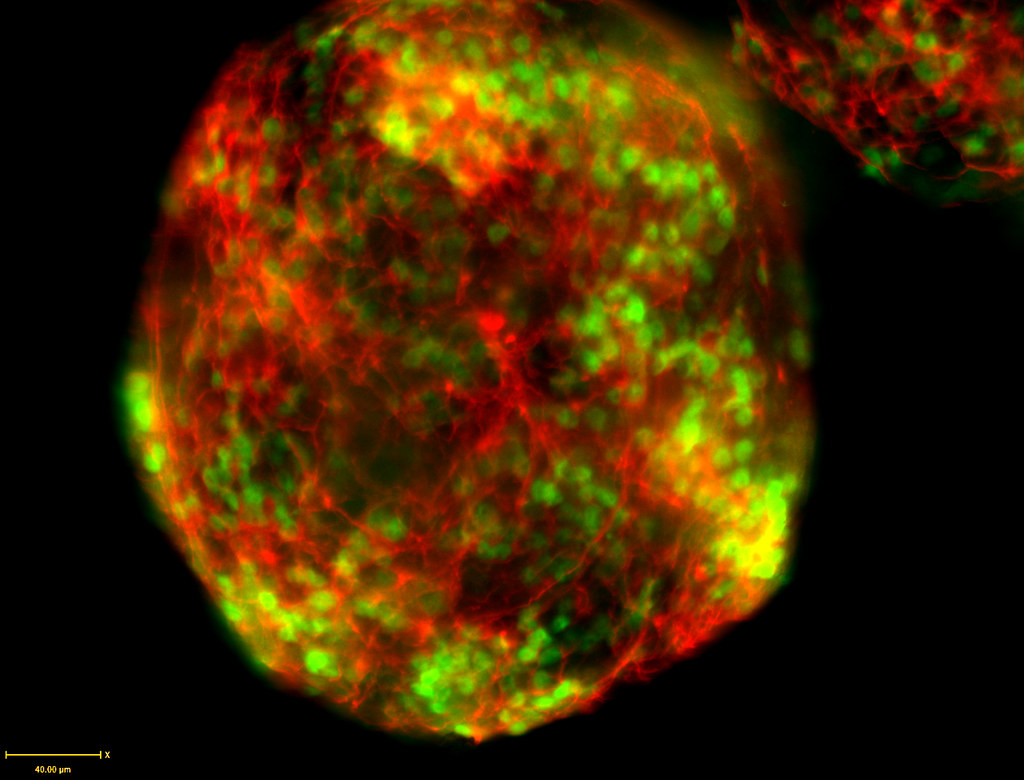

Okay, so here’s what I think I know: CRISPR is a new-ish technology that allows scientists to edit DNA. I remember seeing in articles pictures of little scissors that are supposed to “cut out” the bad parts of strings of DNA, and perhaps even replace those bad parts with good parts. I don’t know how this is supposed to work. It was discovered sort of serendipitously when studying bacteria and how they fight off viruses, I think, and it all started with people in the yogurt industry. CRISPR is an acronym, but I don’t remember what it stands for. What I do know is that a lot of people are talking about it, and that people say it’s revolutionary.

I also know that while ethical worries abound – not only because of the general worries about the unknown side-effects of altering DNA, but because of concerns about people wanting to make things like designer babies – from what my news feed is telling me, there is reason to get really excited. As many, many, m–a–n–y news outlets have been reporting, there is a new study, published in Nature, that a new advance in CRISPR science means that we could correct or cure or generally get rid of 89% of genetic diseases. I’ve heard of Nature: that’s the journal that publishes only the best stuff.

I’ve also heard that people are so excited that Netflix is even making a miniseries about the discovery of CRISPR and the scientists working on it. The show, titled “Unnatural Selection” [sic], pops up on my Netflix page with the following description:

“From eradicating disease to selecting a child’s traits, gene editing gives humans the chance to hack biology. Meet the real people behind the science.”

In an interview about the miniseries, co-director Joe Egender described his motivation for making the show as follows:

“I come from the fiction side, and I was actually in the thick of developing a sci-fi story and was reading a lot of older sci-fi books and was doing some research and trying to update some of the science. And — I won’t ever forget — I was sitting on the subway reading an article when I first read that CRISPR existed and that we actually can edit the essence of life.”

89% of genetic diseases cured. Articles published in Nature and a new Netflix miniseries. Editing the essence of life. Are you excited yet???

So the point of this little vignette is not to draw attention to the potential ethical concerns surrounding gene-editing technology (if you’d like to read about that, you can do so here), but instead to highlight the kind of ignorance that myself and journalists are dealing with when it comes to reporting on new scientific discoveries. While I told you at the outset that I didn’t really know what was going on with CRISPR, I wasn’t exaggerating by much: I don’t have the kind of robust scientific background required to make sense of the content of the actual research. Here, for example, is the second sentence in the abstract of that new paper on CRISPR everyone is talking about:

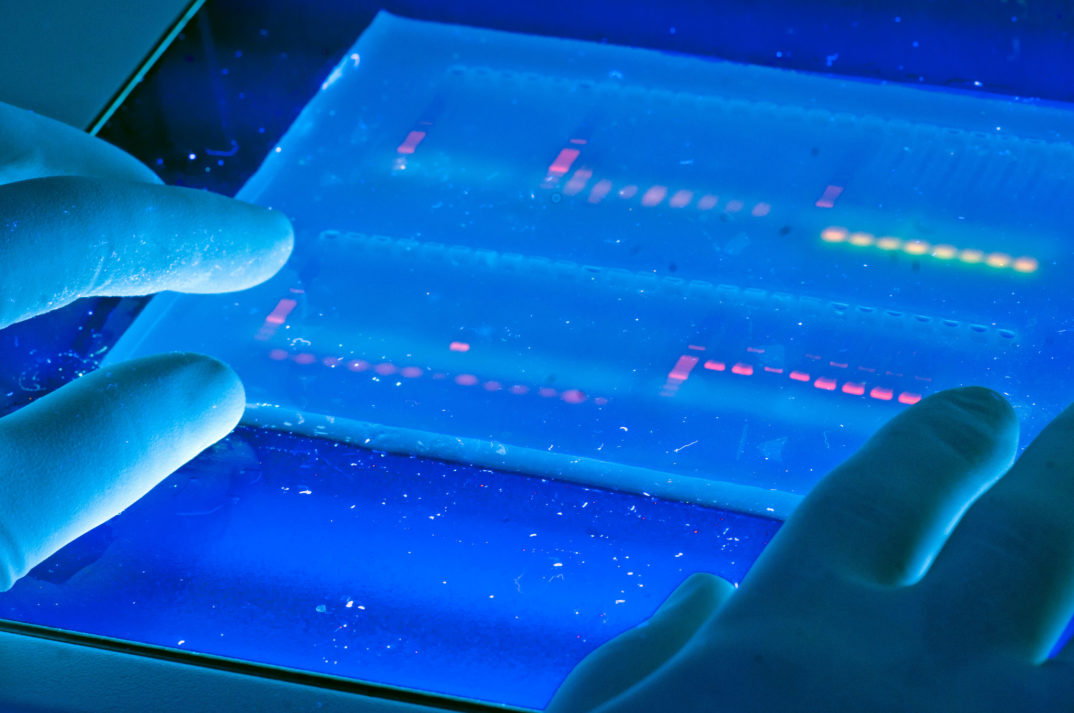

“Here we describe prime editing, a versatile and precise genome editing method that directly writes new genetic information into a specified DNA site using a catalytically impaired Cas9 fused to an engineered reverse transcriptase, programmed with a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that both specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit.”

Huh? Maybe I could come to understand what the above paragraph is saying, given enough time and effort. But I don’t have that kind of time. And besides, not all of us need to be scientists: leave the science to them, and I’ll worry about other things.

But this means that if I’m going to learn about the newest scientific discoveries then I need to rely on others to tell me about them. And this is where things can get tricky: the kind of hype surrounding new technologies like CRISPR means that you’ll get a lot of sensational headlines, ones that might border on the irresponsible.

Consider again the statement from the co-director of that new Netflix documentary, that he became interested in CRISPR after he read about how it can be used to “edit the essence of life.” It is unlikely that any scientist has ever made so bald a claim, and for good reason: it is not clear what it means for life to have an “essence”, nor that such a thing, if it exists, could be edited. The claim that this new scientific development could potentially cure up to 89% of genetic diseases is also something that makes an incredibly flashy headline, but again is much more tempered when it comes from the mouths of the actual scientists involved. The authors of the paper, for instance, state that the 89% number comes from the maximum number of genetic diseases that could, conceptually, be cured if the claims described in the paper were perfected. But that’s of course not saying much: many wonderful things could happen in perfect conditions, the question is how likely they are to exist. And, of course, the 89% claim also does not take into account any potential adverse effects of the current gene editing techniques (a worry that has been raised in past studies).

This is not to say that the new technology won’t pan out, or that it will definitely have adverse side effects, or anything like that. But it does suggest some worries we might have with this kind of hyped-up reaction to new scientific developments.

For instance, as someone who doesn’t know much about science, I necessarily rely on people who do in order to tell me what’s going on. But those who tend to be the ones telling me what’s going on – journalists, mostly – don’t seem to be much better off in terms of their ability to critically analyze the information they’re reporting on. We might wonder what kinds of responsibilities these journalists have to make sure that people like me are, in fact, getting an accurate portrayal of the state of the relevant developments.

Things like the Netflix documentary are even further removed from reality. Even though the documentary makers themselves do not make any specific claims as to understand the science involved, they clearly have an exaggerated view of what CRISPR technology is capable of. Creating a documentary following the lives of people who are capable of editing the “essence of life” will certainly give viewers a distorted view.

None of this is to say that you can’t be excited. But with great hype comes great responsibility to present information critically. When it comes to new developments in science, though, it often seems that this responsibility is not taken terribly seriously.