Election day may have come and gone, but Canadian democracy has weathered a number of alarming turns in recent months. And yet, of all the issues discussed during the campaign, Canada’s “democratic deficit” barely received a mention. Has Canadian democracy survived unscathed or does the threat remain?

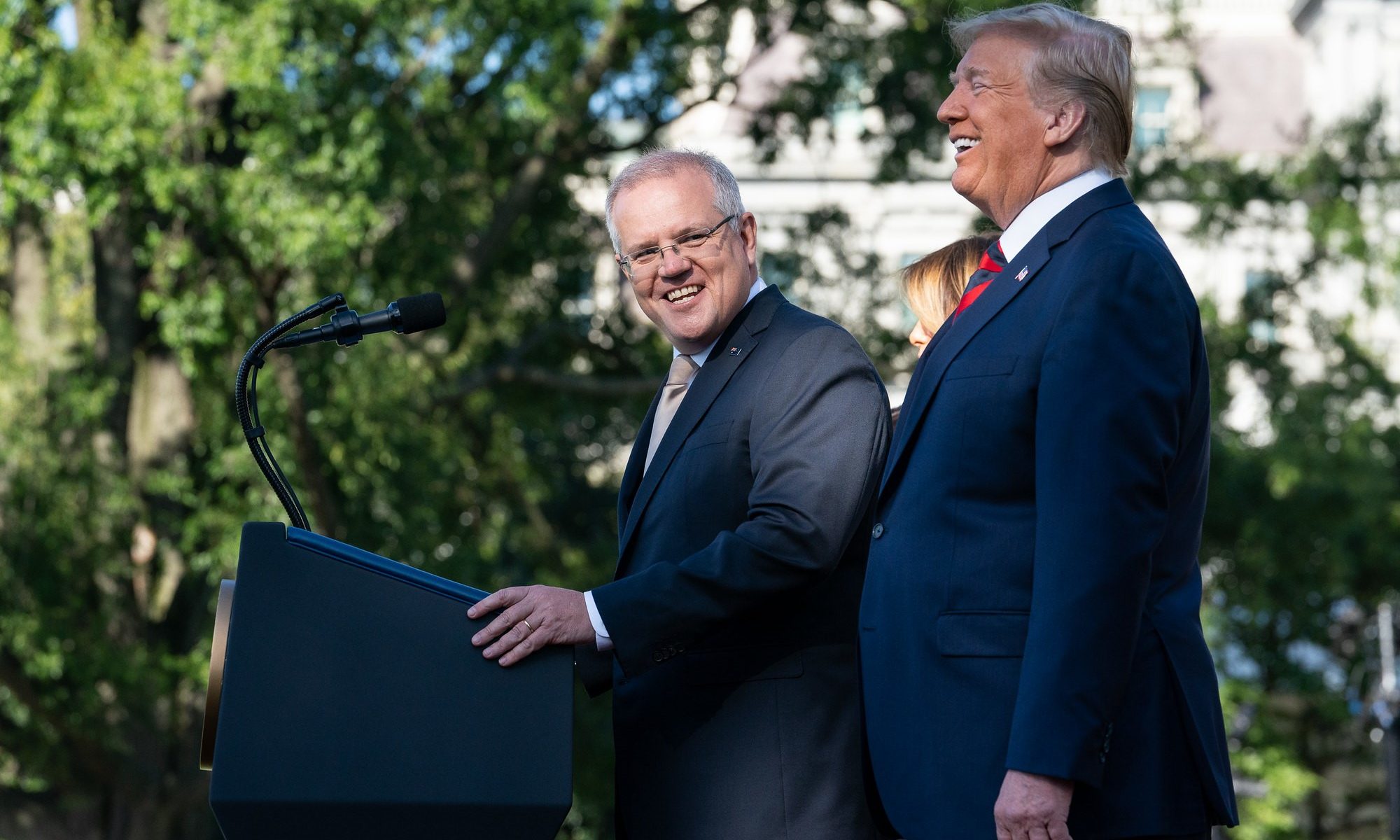

One of the most concerning things about Canada’s constitution is the Office of the Prime Minister. Anyone looking for a description of the prime minister’s powers in Canada’s constitution will be disappointed. Canada’s unwritten constitution functions according to the conventions of Westminster-style parliamentary system (as used in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, India, Belize, and many more countries). The prime minister is appointed as the head of government (the head of the monarchs council of advisors) by the head of state (the monarch) on the basis that they have the confidence of a majority of MPs in the House of Commons. The powers and limitations of the office are mostly based on unwritten convention.

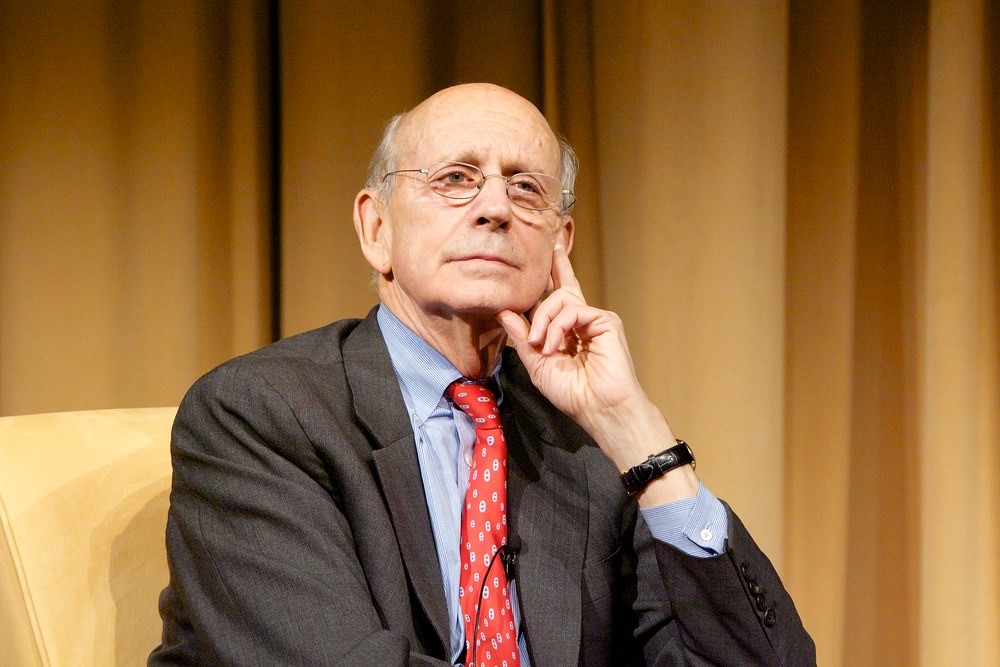

A 2001 book on the topic called Canada’s prime minister “the friendly dictatorship.” And in the decades since, Canadians occasionally wonder if the government has become too centralized in the Office of the Prime Minister. The prime minister has the power to appoint their cabinet, parliamentary secretaries, senators, judges (including the Supreme Court), ambassadors, civil servants, the governor general and the provincial lieutenant governors; they advise the monarch when parliament should sit (something only constitutionally mandated once per year), and they alone advise when elections should be called; all without any parliamentary oversight.

In addition, the prime minister is also usually (but not necessarily) the leader of the political party with the largest caucus of MPs in the House of Commons. Being a party leader provides other perks as the party constitution can shield a leader from accountability from their own caucus and the leader has almost unilateral powers to appoint or deny someone being a candidate for the party (even if the candidate was already selected by party members in their local constituency). Thus, a prime minister cannot only create many incentives to keep MPs quiet and make them toe the party line, but if they don’t the leader can simply prevent them from running again. This means that even those in the prime minister’s own party have little ability to hold their leaders accountable, as we saw late last year.

The relative lack of oversight and accountability for such an unusual amount of concentrated political power is concerning. The only real check on the prime minister is the House of Commons’ vote of non-confidence. Without more political tools, it’s difficult to reign in an incompetent or wayward prime minister. This was recently put to the test when former Prime Minister Trudeau, facing a 20% approval rating and the likelihood of electoral oblivion at the next election, faced increasing calls to step down, even from within his own party. It’s hard to argue that Trudeau’s government was known for its competence, but despite a clear consensus that Trudeau should probably go, Liberal MPs insisted that their party’s constitution did not permit them to replace a leader – despite the fact that a majority of Liberal MPs were eventually calling for Trudeau to quit.

By the end of last year, every other political party backing Trudeau’s minority government publicly stated that they had lost confidence in Trudeau and would seek to vote non-confidence at the first opportunity. So, while it was clear that not only could Trudeau not command the support of the House, and even his own caucus, one would think replacing him would be straightforward. It was not. With the Parliament in recess, there was no way to actually hold a vote of confidence, and without that one check on the powers of the prime minister, Trudeau was able to spend weeks “reflecting” before finally making a decision to resign (he could have waited months longer if he wanted to).

Regardless of how anyone may feel about Trudeau politically, his decaying premiership stands as an objective example of the dangers of a prime minister who refuses to go. Defenders of the state of Canadian democracy may take this as proof that the system works: Trudeau was removed. The truth is that Trudeau weakened the only check on the powers of a prime minister on his way out of office. Rather than resign immediately or simply have the Liberal caucus choose a new leader (as often happens in other parliamentary systems), Trudeau prorogued parliament, preventing a vote and giving the Liberal Party weeks to engage in a protracted leadership campaign while the country was staring down an economic crisis with the United States.

Prorogation – the parliamentary procedure to reset things and start a new session of parliament – isn’t normally controversial. However, twice in the past twenty years a (Liberal and Conservative) prime minister has used this mechanism to avoid an impending vote a non-confidence. Imagine, for example, a clear majority of Congress (including 2/3rds of senators) indicating publicly that they intend to impeach the president, but before a vote can be called, the president closes Congress and prevents it from sitting for months so that people can “cool off.”

This kind of concentrated power lends itself to abuse. Yet, according to constitutional convention, it is only the prime minister that can advise the monarch, and as far as the Canadian media and legal establishment is concerned, this power is almost absolute until a non-confidence vote can actually occur. In other words, any time a prime minister gets a whiff that they might face a non-confidence vote, they are entitled to seek prorogation. And, recall, Parliament only has to sit once per year.

This kind of power is difficult to defend. To escape political danger, a prime minister only has to ignore a minority parliament, claim that it is being dysfunctional, and call for a reset. But the courts of the United Kingdom have already recognized that a prime minister should not have a unilateral say. When Boris Johnson advised the monarch to prorogue Parliament during Brexit negotiations, the courts ruled that the advice was unlawful because it prevented Parliament from carrying out its constitutional function. So, when a prime minister is facing a revolt from roughly his entire caucus and deadlocks Parliament by refusing to hand over documents relevant to parliamentary oversight, it’s reasonable for people to see this as preventing Parliament from performing its duty.

This issue is bigger than Trudeau, it’s about the Office of the Prime Minister. The legitimacy of all executive power of the prime minister (and everyone they appoint) should not rest on interpretations of vague conventions only a select few constitutional scholars will understand. Clearly these unwritten conventions are ripe for abuse, and recent evidence strongly suggests that these problems will only get worse. Some kind of constitutional amendment governing the powers of the prime minister ought to be formalized. Unfortunately, the powers of the prime minister were barely discussed during the campaign (I doubt many even understand the problem). Canadians may have voted, but democracy has lost.