An incendiary essay is currently making the rounds. Glenn Ellmers’s “‘Conservatism’ is no Longer Enough” is a call to arms: “The United States has become two nations occupying the same country.” The essay details a kind of foreign occupation:

most people living in the United States today—certainly more than half—are not Americans in any meaningful sense of the term. […] They do not believe in, live by, or even like the principles, traditions, and ideals that until recently defined America as a nation and as a people. It is not obvious what we should call these citizen-aliens, these non-American Americans; but they are something else.

Given this dire situation where there is “almost nothing left to conserve,” “counter-revolution” represents “the only road forward.” Those brave enough to grasp this grave truth also possess the clarity of vision to see that “America, as an identity or political movement, might need to carry on without the United States.” For if true patriots fail to find the courage to mobilize and take action, “the victory of progressive tyranny will be assured. See you in the gulag.”

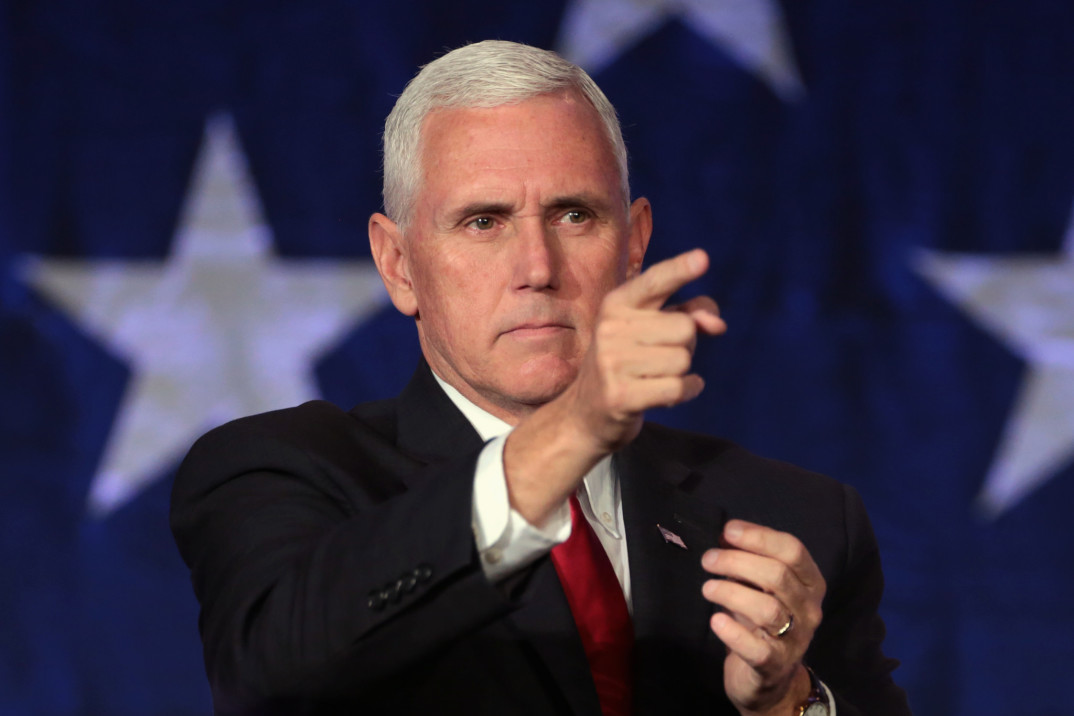

While it may seem irresponsible to grant such obvious propaganda additional attention, Ellmers’s essay is worthy of consideration for two reasons. First, this is not your run-of-the-mill internet debris. It bears the seal of a prominent conservative think tank. Published by The American Mind with direct ties to the Claremont Institute (where Ellmers graduated and serves as fellow), the essay is endorsed by a body with not insignificant cachet. The various fellows and graduates, for instance, have ties to major universities. It would be a mistake to see this as obscure preaching to a small flock; this narrative is emblematic. It’s an intellectualized hard-right manifesto serving as mission statement for the Claremont Institute for the Study of Statesmanship and Political Philosophy whose name Ellmers invokes.

Second, the essay provides a compelling framework by which to understand the motivations behind a number of recent events — the various efforts to overturn the results of the presidential election, the January 6th Capitol riot, as well as voting legislation in Georgia (and elsewhere) attempting to restrict the franchise to “real” Americans. Like Michael Anton’s “The Flight 93 Election” (another Claremont fellow whose work was published by the same body), Ellmers’s essay paints the current political moment as a desperate choice: fight or face extinction, rush the cockpit or die.

Ellmers’s essay has received attention in no small part due to its eerie similarity to Weimar-era German political writings. Echoing the kind of language used by Carl Schmitt – the constitutional scholar and jurist who embraced National Socialism – Ellmers emphasizes the need to declare a state of emergency and purge those who have infiltrated the state and subjected American politics, all in an act of restoration and purification. “What is needed, of course,” Ellmers claims, “is a statesman who understands both the disease afflicting the nation, and the revolutionary medicine required for the cure” — a pronouncement which seems strikingly similar to Schmitt’s explanation of the role of the sovereign to normalize the situation by embracing the responsibility to deliver the miracle of the decision – that is, the extra-legal authority to say whether everyday legal norms should apply.

Likewise, Ellmers’s essay seconds Schmitt’s conviction that the basis of politics rests on distinguishing friend from foe and treating them accordingly. For any state to continue to be, it must be willing and able to forcibly expel those who might undermine its fundamental homogeneity in order to save itself from corruption from within. Again, following Schmitt, Ellmers issues a dire warning on the supposed political virtue of tolerance and questions our blind faith in democracy’s ability to assimilate conflicting and antagonistic viewpoints and house them under the same roof.

Lost in all the fascist rhetoric is an important philosophical problem. The challenge is familiar to students of political obligation: how can citizens feel any tie to the law when it isn’t their team who’s making the rules? It is what David Estlund has called the “puzzle of the minority democrat”: how can those in the minority consider themselves self-governing if they are subject to laws they have not explicitly endorsed?

This is no small thing; resolving this tension is the key to the bloodless transition of power. Ensuring citizens can adequately identify with the law and see themselves sufficiently reflected in their government is a necessary component of the exercise of legitimate political authority. We need a compelling answer for how citizens might still see themselves as having had a hand in authoring these constraints even when their private preferences have failed to win the day. Why should those in the minority sacrifice their own sense of what is right simply because they lack numbers on their side on any particular occasion?

Our answers to this puzzle often begin by emphasizing that democratic decision-making is essentially about compromise. Majority rule acknowledges our basic equality by publicly affirming the worth of each citizen’s viewpoint. It privileges no single individual’s claim to knowledge or expertise. It grants each citizen the greatest share of political power possible that remains compatible with people’s basic parity. From there, explanations begin to diverge.

Some accounts emphasize the duty to live by the result of the game in which we’ve been a willing participant. Others highlight the opportunity to impact the decision, voice concerns, and engage in reason-giving. A few maintain faith in the majority’s ability to come to the “correct” decision.

Regardless of the particulars, each of these accounts makes a virtue of reciprocity; individual freedom must be balanced against the equally legitimate claims to liberty by one’s fellows. When we refuse to acknowledge this, we usurp others’ right to equal discretion in shaping our shared world and thus violate our moral commitment to the fundamental equality of people.

These considerations about how best to accommodate deep, and potentially incompatible, disagreement have important implications for our politics today. For example, the ongoing debate over reforming the filibuster is a conversation about, among other things, the appropriate portion of power those in the minority should wield. Different people articulate different visions of the part the opposition party needs to play. But we seemingly all agree that this role must be more robust than one wherein those in the minority simply bide their time until they can rewrite the law and install their own private political vision. Instead, we must continue to articulate the significant demands the concept of loyal opposition makes on all of us. Responsible statesmanship is not solely the burden of those who wear the crown.