This piece is part of an Under Discussion series. To read more about this week’s topic and see more pieces from this series visit Under Discussion: “Woke Capitalism.”

This year, NYC Pride is supported by (take a breath) T-Mobile, MasterCard, Hyatt, TD Bank, Macy’s, Delta, Virgin Atlantic, Target, HSBC, Unilever, Coca-Cola, Proctor and Gamble, AXA, Chase, American Airlines, Netflix, Airbnb, Nissan, IBM, Pepsico, Wells Fargo, United Airlines, TD Ameritrade, Microsoft, Deloitte, Starbucks, Johnson and Johnson, and Uber. Never before has a left-wing political movement enjoyed such overwhelming corporate support.

Companies have long acknowledged the value of “pink money.” Known to corporate demographers as “DINKY” (dual income, no kids), most gay couples have higher average levels of disposable income. As such, they are highly desirable customers and are often specially targeted. American Airlines, for example, formed a team devoted to gay and lesbian marketing and saw its earnings from this demographic rise from $20 million to $194 million in just five years. Pink money is approaching the buying power of all Black Americans, of Hispanic Americans, and exceeds that of Asian Americans.

Corporations have nothing to fear, and perhaps some good customers to gain, by supporting the LGBTQ+ movement.

The current outpouring of corporate support for the LGBTQ+ movement is an obvious example of so-called “Woke Capitalism.” Defining this term is difficult, as Ken Boyd explains here; its critics and defenders often seem to have different ideas of what it means. Boyd claims the criticisms of Woke Capitalism tend to fall into two broad camps. Capitalist critiques claim that the “woke” part of Woke Capitalism is bad for business, while conservative critiques reject the progressive values that Woke Capitalism promotes. I want to offer a third kind of critique — one from the political left.

If Woke Capitalism is meant to be supportive of progressive values, shouldn’t those on the political left be in favor of it?

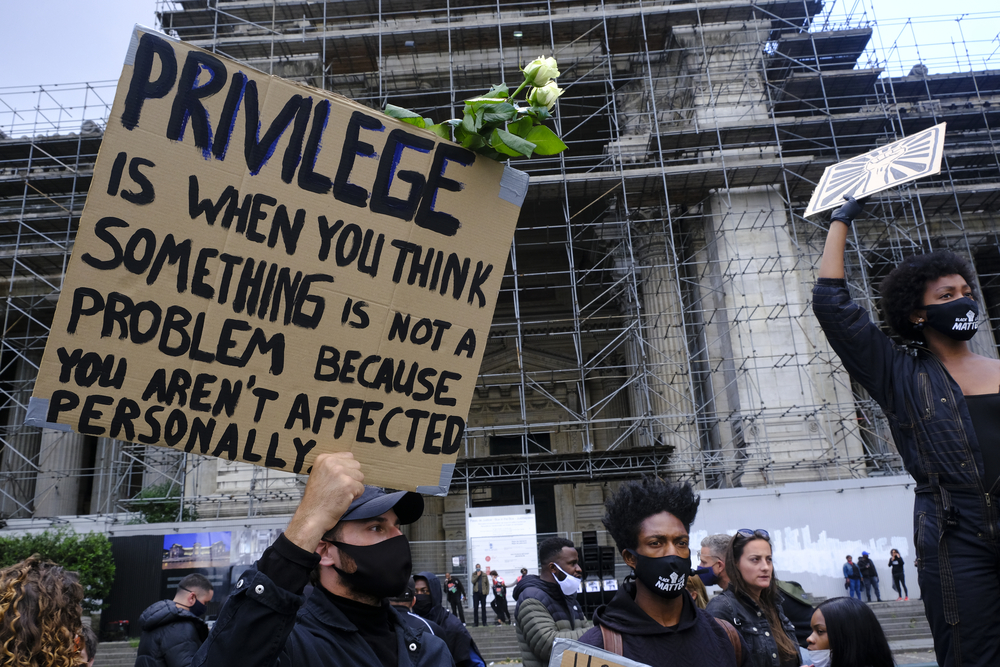

Not necessarily. For example, many gay rights activists reject their newfound corporate support as “Rainbow Capitalism,” mere virtue signaling or “pinkwashing.” This is the most common left-wing critique of Woke Capitalism — that it’s cynical, insincere, and perhaps even hypocritical.

The critics are right in that there is something insincere about Woke Capitalism. For Pride Month, the major software company Bethesda changed its Twitter avatars to rainbow versions. Well, they did so in the USA, France, Brasil, New Zealand, Italy, Netherlands, and Germany. But Bethesda decided to leave its icon solid black in the Middle East, Turkey, and Russia. The same weakness of conviction is clear from the history of the gay rights movement. No major corporation supported the movement while it was still struggling for social and political recognition decades ago.

Arguably, these corporations are chasing popular opinion on these issues, rather than attempting to change it.

But the pinkwashing critique only goes so far. For one thing, being cynical, insincere, or even hypocritical does not necessarily mean your actions are wrong. It’s still good to give to charity, even if the reason you’re doing it is simply to get a tax credit or to impress a colleague. Even if the Woke Capitalists are doing what they’re doing cynically, they could still be doing good.

It’s also implausible that Woke Capitalism is entirely cynical. The people working in executive corporate roles are, demographically speaking, more likely to be politically liberal. Many of these people are surely genuine in their political convictions and are sincerely trying to do some good, as they see it. So we can’t dismiss Woke Capitalism as entirely hypocritical virtue signaling. Whether or not you agree with the progressive values Woke Capitalists push, we can surely acknowledge there is sincere goodwill behind at least some of these efforts.

What should most concern us about Woke Capitalism, however, is not merely the sincerity of its corporate practitioners. Instead, we should consider its actual political effects.

Imagine you are Mr. Corporate McCapitalist (if it helps, picture a hybrid of Mr. Peanut and Gordon Gekko). Things are very simple. You want a high return on your capital and you don’t want disruptive left-wing political movements getting in the way with policy interventions that empower workers or raise taxes on your profits. Uh-oh! The working class looks like it might come together and vote for meaningful political change! Workers are talking about unionization and politicians are advocating laws that would make you “pay your fair share” to support a decent welfare and education system! What can you do to stop this madness?

Sure, you could fund corporate propaganda campaigns or pro-corporate opposition candidates. These are both solid, well-established moves. But, if you’re feeling just a bit more ambitious, you might be able to pull a political Indiana Jones — replacing the golden idol with a bag of sand (or, in your case, replacing dangerous traditional left-wing economic causes with harmless left-wing “woke” causes).

This is, in cartoon form, the alternative left-wing critique I have in mind;

Woke Capitalism operates as a misdirection, sapping political movements of the focus and energy needed to make tangible gains.

Woke Capitalism has been incredibly effective at directing public and media attention. It has played a decisive role in pushing the most divisive social issues, so-called “wedge issues,” into the political limelight. Take Nike’s controversial Colin Kaepernick advertising campaign. It boosted Nike sales by 31%, creating $6 billion in brand value in the process. It was also perfect fuel for the culture war fire. “It doesn’t matter how many people hate your brand as long as enough people love it,” explained Phil Knight, Nike founder. The political controversy saturated political discussion for months.

These divisive political fights over “woke” issues such as race and gender inevitably divert precious media attention and grassroots political effort from likely more impactful economic struggles — struggles that threaten corporate financial interests. Our society uses more attention and energy debating something as insignificant as who should be allowed to use what bathroom than it does debating the merits of a carbon or wealth tax. CEOs must be pinching themselves to make sure they’re not dreaming.

The more controversial, engaging, and fierce the fight over these “woke” issues becomes the safer corporate profits.

According to this critique, Woke Capitalism is objectionable because it (very effectively) distracts the political left from taking effective action on the most impactful political struggles. By going woke, the corporate world has managed to neuter its traditional political opposition. Left-wing politics is no longer a significant threat to corporate economic interests. Instead, the political left sees corporations as allies in the culture war.

Politics is the art of the possible. It demands we do what we can with the time and resources we happen to have at hand. Therefore, some of the most important political questions are (and ought to be): What should we prioritize? On what should we focus our limited attention? Toward what goal should we put our limited resources? These are difficult questions to answer, but we can’t afford to let corporations answer for us.