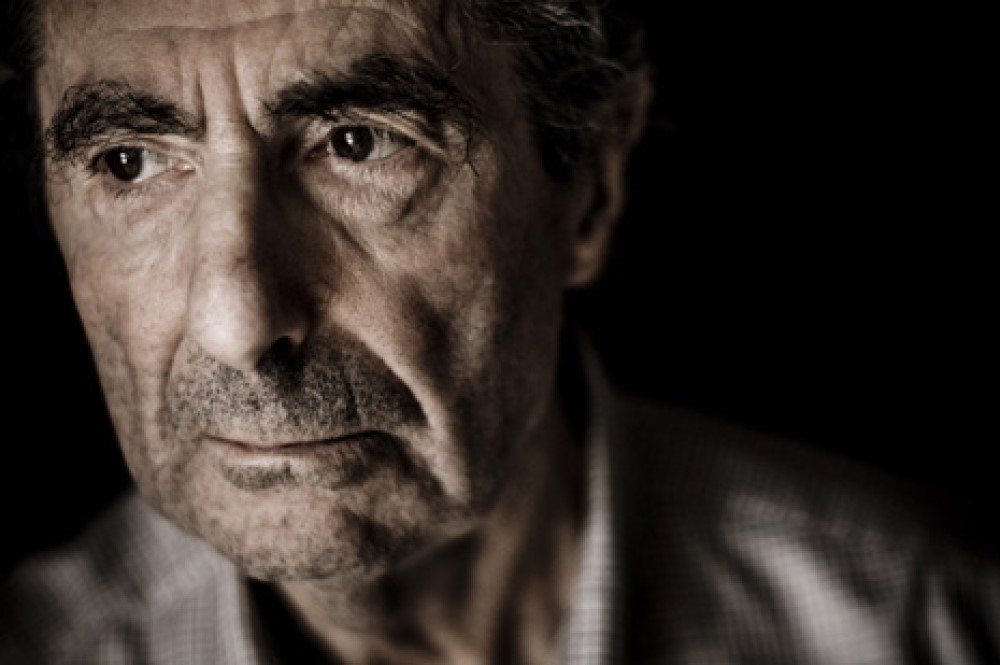

The fall of a literary star is something to behold. At the beginning of April, Blake Bailey was the toast of the literary world; his new biography of the novelist Philip Roth had been published to acclaim, landing on The New York Times best-seller list. But by the end of the month, Bailey’s fortunes were laid low by horrific allegations made against him, including that he raped two women as recently as 2015 and “groomed” middle school girls when he was a teacher in the 1990s. After they surfaced, his publisher, W.W. Norton, took the rare step of stopping promotion and shipment of the book just days after his literary agent dropped him as a client.

One might very well be tempted to say, “good riddance.” And there is no reason to defend Bailey personally; the accusations against him are credible and multiple. Yet Norton’s decision raises an important philosophical question: how evil does a person have to be in order for it to be impermissible to disseminate their art?

One problem we are immediately confronted with is the issue of arbitrariness. Are there any criteria for setting a threshold for the badness of a person such that it is impermissible to disseminate their art? One fruitful perspective on this question comes from rule consequentialism, which evaluates the rightness of acts according to how much the rules permitting or obligating those acts would promote overall good consequences, however the latter are spelled out. This perspective helps with the problem of arbitrariness because it prompts us to compare, in a morally meaningful way, different thresholds in terms of their hypothetical consequences. Not publishing Bailey’s book implies a rule setting the threshold for permissible publication at rape or sexual assault (or, presumably, worse). What would be the effect of consistently applying that rule as compared to a world in which the rule permitted disseminating just about anyone’s art?

Shockingly, not a few great artists have either admitted to or been credibly accused of rape or worse. William Golding, author of Lord of the Flies, details his attempted rape of a 15-year-old girl named Dora in his unpublished memoir Men and Women. William S. Burroughs killed his wife; Norman Mailer came close. Eldridge Cleaver famously wrote about raping white women as an act of revolutionary violence. Of course, Woody Allen stands credibly accused of sexually assaulting his daughter, Dylan Farrow; Roman Polanski was actually convicted of drugging, raping, and sodomizing a 14-year-old girl. And then there’s Bill Cosby. And Hitler, whose Mein Kampf chillingly lays out the dictator’s plans for the extermination of world Jewry.

The point is this: applied consistently, the rule implied by the act of not publishing Bailey’s work would deprive us in some cases of great works of art, and in other cases of important information. Publishers, producers, and art dealers, hesitant to invest in works that they might end up having to pull, might refuse to enter into contracts with artists without intrusive background checks. Yet the world of the consistently applied rule would also be better than ours in certain respects: victims would not be retraumatized by the fame of their abusers; artists might be deterred from committing heinous behavior by the thought that it would negatively affect their careers. How one weighs these different effects is a matter of fine judgment. In my view, the benefits seem speculative, while the costs seem probable and cumulatively great. But I could be wrong.

Another idea is that it is wrong to benefit people who are guilty of heinous moral wrongs, perhaps because it encourages or emboldens them to continue behaving as they do, or because — if they continue to commit badly — we may take on partial responsibility for their wrongdoing. Here, I think, we can do better than simply throwing up our hands and concluding that we must benefit wrongdoers if we want to benefit from their art— or at least, that we must benefit only them. For example, in Bailey’s case, Norton could have decided to donate all of the proceeds minus Bailey’s royalties from his book to rape survivors’ organizations. This outcome would surely not encourage Bailey, as it constitutes a clear condemnation of him. This would also be a great way of establishing some symbolic distance between the publisher and the author.

There are other compelling arguments against publication from a non-consequentialist perspective. Some may think that it is simply wrong to honor individuals who are guilty of heinous moral wrongs. By “honor” I mean something like expressing admiration for a person in a way that tends to enhance their social status. Perhaps this is wrong because such individuals do not morally deserve to be honored — and not because honoring them would bring about bad consequences. Publishing a person’s book certainly does honor them; thus, it is wrong to publish. The trouble with this argument is that it is arbitrary: when is a moral wrong so heinous that the obligation applies? Is there any reason to prefer the rule that sets the threshold for heinous acts at the killing of ten people rather than the killing of one? There doesn’t seem to be. Without any reason to draw the line at rape or sexual assault rather than, say, the extermination of the entire human race, we might as well choose the higher bar. But if we draw the line at the higher bar, then in effect publishing anyone is permissible.

That we nevertheless tend to believe it is wrong to honor people who don’t deserve it helps to explain why the question whether it is wrong to publish evil people will remain with us for the foreseeable future. Human beings have a well-documented aversion to ambivalence, preferring to hold either wholly positive or wholly negative attitudes towards persons and things. But publishing evil people puts us in the uncomfortably ambivalent position of having to appreciate and honor their talents while abhorring their deeds. This will never be a natural fit for beings like us.