Human beings are wildly diverse. We differ in height, skin color, hair type, cultural practices, beliefs about the afterlife, and even in opinions on whether Batman could really beat Superman. Yet, despite all these differences, some things unite every one of us across history and across the globe. We all breathe air. We all need food and water. We all sleep. We are all carbon-based lifeforms. And we have all shared one biological constant: half of our genetic makeup comes from a biological mother, and half from a biological father.

However, this seemingly universal constant — that every child must inherit genetic material from both a mother and a father via a sperm and egg — may not hold for much longer. A team at the Oregon Health and Science University may have taken the first steps toward disrupting it.

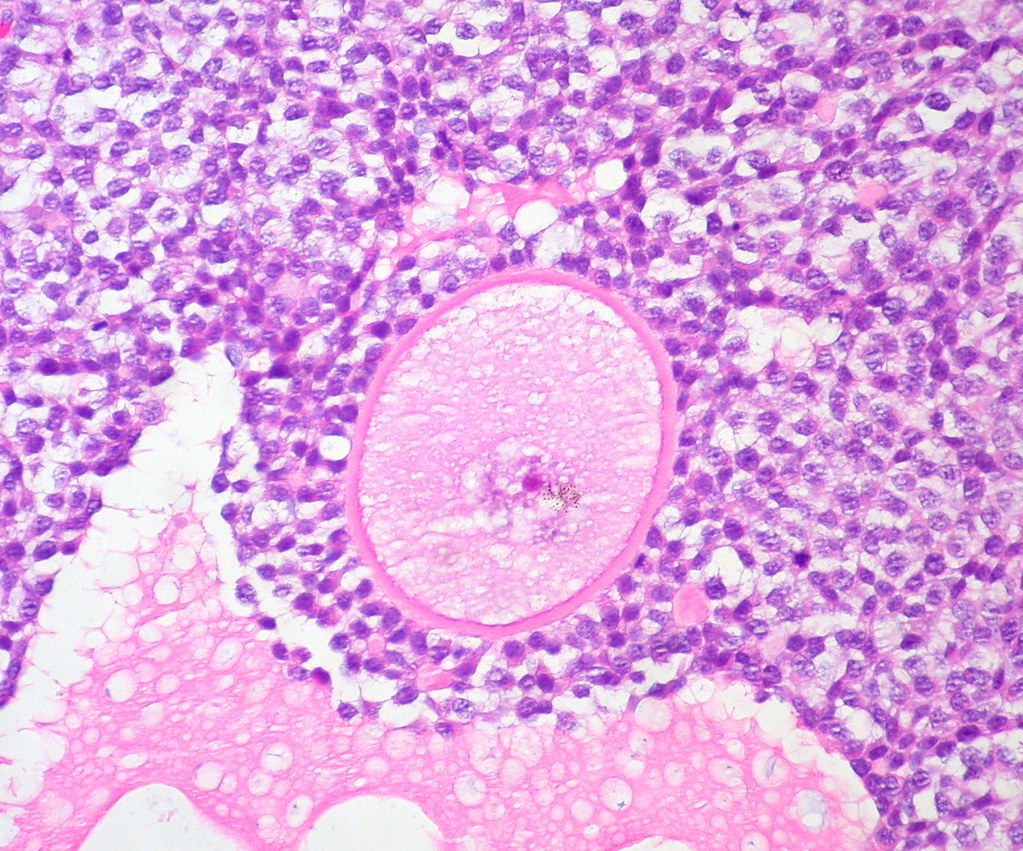

In a recent study published in Nature Communications, researchers reportedly created an early-stage human blastocyst (a cluster of cells with the potential to develop into an embryo) using sperm and a genetically modified egg. Instead of relying on the egg’s original DNA, the researchers replaced its genetic material with DNA taken from a skin cell. Although the technique is still in its infancy, if refined, it could open new possibilities for people with fertility challenges to have genetically related children. Even more striking, it might one day allow same-sex couples to have children who are biologically related to both partners.

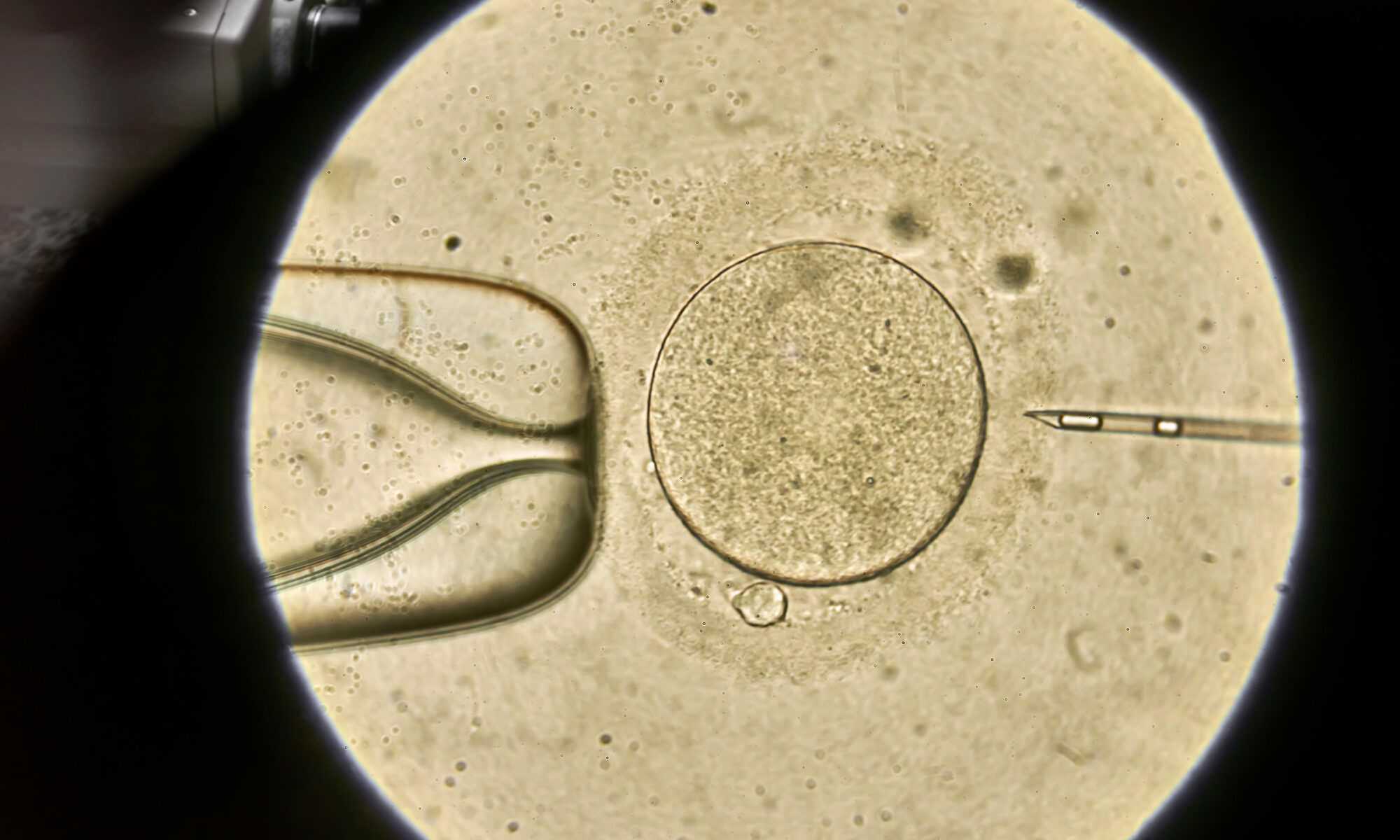

Of course, humanity’s attempts to shape, guide, and expand our reproductive horizons is an age-old endeavor. Aristotle is thought to have suggested using cedar oil, lead ointment, or frankincense oil to prevent pregnancy. In the 18th century, Giacomo Casanova wrote about his attempts to create a cervical cap to prevent pregnancy. In the 20th century, Serge Voronoff began transplanting chimpanzee and baboon testical material into men suffering from impotence. More recently, and probably most famously, in 1978 using in virto fertilization (IVF), the world’s first “test tube” baby, Louise Brown was born. And while IVF success rates are far from 100%, since that point, more than 10 million children have been born using IVF, many to people who would have struggled to reproduce otherwise.

There are also the now-infamous actions of Jiankui He, who in 2018 shocked the world by announcing that he had overseen the genome editing, gestation, and birth of twin girls — code-named Lulu and Nana.

Despite these advances, one thing remained constant: reproduction still relied on sperm and egg, each carrying their respective genetic material. Even Louise Brown — whose birth marked a turning point in history — began life with the same genetic foundation as all of us. In that sense, humanity’s genetic continuity, what the United Nations terms “the heritage of humanity” has remained (largely) unbroken.

Yet, what the Oregon team have demonstrated, albeit at the earliest and most foundational stage, is that such a unified genetic legacy might soon be overturned.

But what exactly did they do? In simple terms, the team started by removing the nucleus from an unfertilized donor egg cell. They then took the nucleus from a skin cell and placed it into that empty egg. Next, using a process they called mitomeiosis, they triggered the egg to discard half of its genetic material. This step was crucial, because while our cells normally contain 46 chromosomes, an egg must only have 23. That way, when it combines with a sperm cell — which also carries 23 chromosomes — the resulting fertilized egg has the full set of 46 chromosomes needed for typical development. Once the egg was adjusted to the correct number of chromosomes, sperm was introduced, fertilization took place, and the process of mitosis (cell division) began.

The team did not do this just once, however. Like all good scientists, they wanted to replicate the results and identify any patterns. They conducted this process 82 times. Out of those 82 modified and fertilized eggs, 91% of them exhibited some form of abnormality. Furthermore, none of them were allowed to develop beyond six days. What this means is that there is a very high failure rate, and that given more time, even those that seemed to have developed according to an expected trajectory might develop chromosomal faults or abnormalities. So, it seems safe to say that the practice isn’t ready for widespread deployment just yet.

What’s more than this, there are a huge raft of ethical and legal barriers that would prevent implantation of a modified, fertilized egg cell just yet. For example, in the UK, which has lead the way in the field of not only reproductive medicine (it is where Louise Brown was born) but also regulation, there are explicit safeguard preventing the implantation of embryos resulting from modified eggs or sperm (specifically, Section 3 of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008).

Nevertheless, the fact that scientists were able to do this — that they were able to create what appears to be the first tentative stages of blastocyst development, and thus life, using genetic material from a person’s skin cell — is remarkable and, for some, troubling.

As alluded to, the issue of heritage and relationships to the rest of humanity rears its head. What does it mean to relate to the rest of humanity when your genetic material, the very blueprints from which you are constructed, have a different origin story than practically everyone else alive or who has ever lived? What impacts might this have on society or our idea of family?

Such questions are not new. With Louise Brown’s birth came an avalanche of opinions and arguments. Some praising the medical breakthrough. Others decrying it as an affront to nature. One common point of comparison was Aldous Huxley’s 1934 novel Brave New World in which sexual reproduction has been outlawed; replaced by a reproduction in the lab. As the Geneticist Robert J. Berry said in an interview with TIME magazine shortly after Louise Brown’s birth “we’re on a slippery slope,” “Western society is built around the family; once you divorce sex from procreation, what happens to the family?” Similar concerns had already surfaced with the advent of modern contraception, such as the pill, though philosophers like Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex rejected the idea that separating sex from reproduction would destroy the family. Since then, we have seen that while the prevalence of the typical nuclear family may have fallen, in its place has come new family dynamics, be those single parents, co-parents, the extended family, the blended family, or even the childless family. What hasn’t happened, however, is the destruction of the family; merely its evolution.

I would hazard a guess that, if or when children are conceived and birthed via the mitomeiosis method, the family unit wouldn’t implode like some suggested it might with Louise Brown’s birth. But, like with Louise Brown’s birth, I think there are some legitimate questions to be asked — maybe even answered — about their relationship with the rest of humanity. In the case of Louise Brown, the defining feature was how the egg was fertilized. With mitomeiosis, the question seems to be more what has been fertilized, and from where did it come?

Children born from mitomeiosis would stand apart from the rest of humanity in a very foundational way. I guess the problem we would need to consider is whether it matters? Even if mitomeiosis-enabled reproduction does in some sense rupture humanity’s genetic continuity which has existed for countless millennia, do we care? Is it something that we should place any value on?

Human history suggests not. What matters most is not that families follow a universal genetic formula, but that they provide love, care, and belonging. Louise Brown’s birth brought hope and joy to millions who longed for children. If mitomeiosis can extend that same gift to those who are currently excluded, then perhaps the true value lies not in preserving continuity, but in creating new connections.