Imagine if it became widely-reported that police officers had been intentionally killing Black Americans for the expressed reason that they are Black. Public outrage would be essentially universal. But, while it is true that Black Americans are disproportionately the victims of police use of force, including lethal force, it seems unlikely that these rights violations are part of a conscious, intentional scheme on the part of those in power to oppress or terrorize Black citizens. At any rate, the official statements from law enforcement regarding these incidents invariably deny discriminatory motivations on the part of officers. Why, then, are we seeing calls to defund the police?

The slogan “Defund the Police” has been clarified by Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza on NBC’s Meet the Press: “When we talk about defunding the police, what we’re saying is, ‘Invest in the resources that our communities need.’” The underlying problem runs deep: it is rooted in an unrelenting devaluation of communities of color. Rights violations by police are part of a larger picture of racial inequality that includes economic, health, and educational disadvantages.

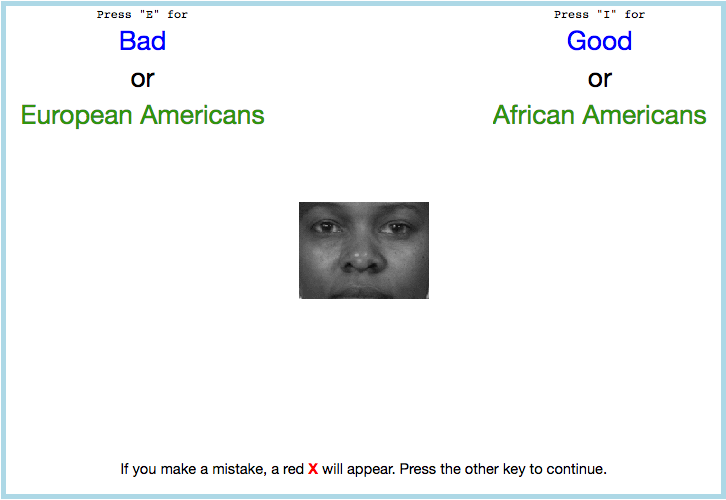

The sources of this inequality are mostly implicit and institutional: a product of the unconscious biases of individuals, including police officers, and prejudicial treatment “baked into” our institutions, like the justice system. That is, social inequality seems to be systemic and not an intentional program of overtly racist policies. In particular, most of us feel strongly that the all-to-frequent killing of unarmed Black citizens, though repellent, has been unintentional.

But does this distinction matter? A plausible argument could be made that the chronic, unintentional killing of unarmed Black men and women by police is morally on a par with the intentional killing of these citizens. Let me explain.

Let’s begin with the reasonable assumption that implicit racial bias, specifically an implicit devaluation of Black lives, impacts decisions made by all members of our society, including police officers. What is devaluation? Attitudes toward enemy lives in war throws some light on the concept: each side invariably comes to view enemy lives as less valuable than their own. Even unintended enemy civilian casualties, euphemistically termed “collateral damage,” become tolerable if the military objective is important enough. On the battlefield, tactical decisions must conform to a “tolerable” relation between the value of an objective and the anticipated extent of collateral damage. This relation is called “proportionality.”

By contrast, policing is intended to be a preventative exercise of authority in the interest of keeping the peace and protecting the rights of citizens, including suspected criminals. Still, police do violate rights on occasion, and police officials operate with their own concept of proportionality: use of force must be proportional to the threat or resistance the officer anticipates.

Ironically, rights violations usually occur in the name of the protection of rights; when, for example, an officer uses excessive force to subdue a thief. Often, these violations are regarded as regrettable, but unavoidable; they are justified as the price we pay for law and order. But, in reality, these violations frequently stem from implicit racial biases. What’s more, the policy of “qualified immunity” offers legal protections for police officers and this disproportionately deprives Black victims of justice in such cases. This combination of factors has led some to argue that police authority amounts to a form of State-sponsored violence. These rights violations resemble wartime collateral damage: they are unintended consequences deemed proportional to legitimate efforts to protect citizen’s rights.

Now consider the following question posed by philosopher Igor Primoratz regarding wartime collateral damage: is the foreseeable killing of civilians as a side-effect of a military operation any morally better than the intentional killing of civilians. Specifically he asks, “suppose you were bound to be killed, but could choose between being killed with intent and being killed without intent, but as a side-effect of the killer’s pursuit of his end. Would you have any reason for preferring the latter fate to the former?”

Imagine two police officers, each of whom has killed a Black suspect under identical circumstances. When asked whether the suspect’s race was relevant to the use of force, the first officer says, “No, and I regret that deadly force was proportional to the threat I encountered.” The second officer says, “Yes, race was a factor. Cultural stereotypes predispose me to view Black men as likely threats, and institutional practices in the justice system keep the stakes for the use of lethal force relatively low. Thus, I regret my use of deadly force that I considered proportional to my perception of the threat in the absence of serious legal consequences.”

The second officer’s response would be surprising, but honest. Depictions of Black men in particular as violent “superpredators” in the media, in movies, and by politicians, are ample. Furthermore, the doctrine of qualified immunity, which bars people from recovering damages when police violate their rights, offers protection to officers whose actions implicitly manifest bias.

In the absence of damning outside testimony, the first officer will be held blameless. The second officer will be said to have acted on conscious biases and his honesty puts him at risk of discipline or discharge. Although the disciplinary actions each officer faces will differ, the same result was obtained, under identical circumstances. The only difference is that the second officer made the implicit explicit, and the first officer simply denied that his own implicit bias was a factor in his decision.

Where, then, does the moral difference lie between, on one hand, the foreseeable violation of the rights of Black lives in a society that systemically devalues those lives, and, on the other hand, the intentional violation of the rights of Black lives? If the well-documented effect of racial bias in law enforcement leads us to foresee the same pattern of disproportionate rights-violations in the future, and we do nothing about it, our acceptance of those violations is no more morally justified than the acceptance of intentional right-violations.

That is, if we can’t say why the intentional violations of Black rights is morally worse than giving police a monopoly on sanctioned violence under social conditions that harbor implicit racial biases, then sanctioning police violence looks morally unjustifiable in principle. That is enough to validate the call to divert funding from police departments into better economic, health, and educational resources for communities of color.