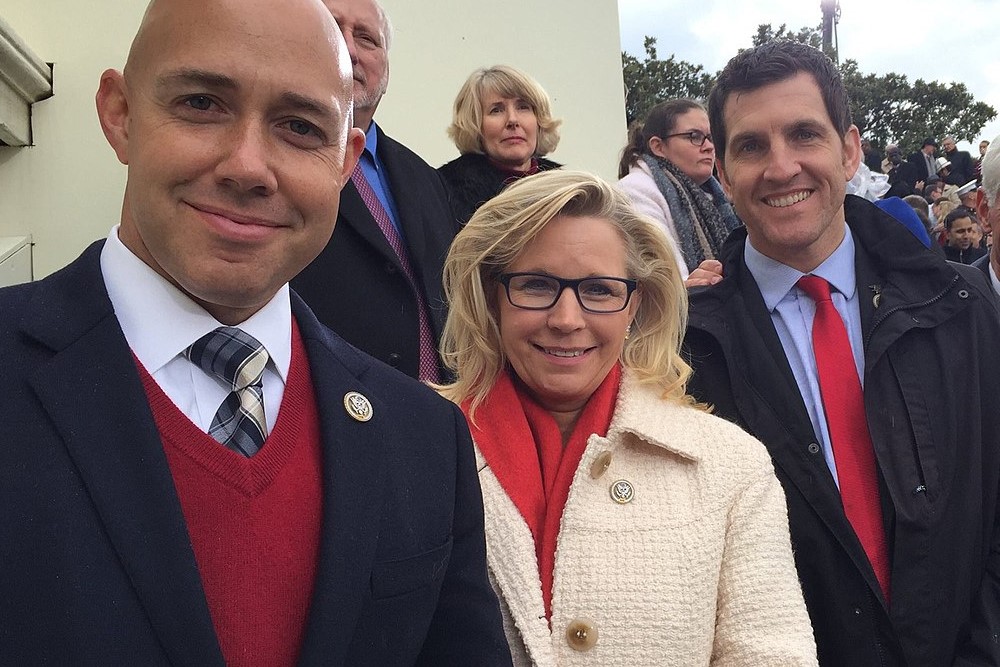

On May 12th, Republicans in the House of Representatives voted to remove Wyoming congressperson Liz Cheney from her leadership position as their conference chair. Previously the third-highest ranking member of the Republican Party in the House, Cheney’s responsibilities were focused primarily on maintaining an organized, unified approach to policy and governance among Republican lawmakers. Earlier in 2021, Cheney came under fire from her party members when she publicly criticized former President Donald Trump’s rhetoric and behavior — including voting to support Trump’s second impeachment trial. After surviving an initial vote to revoke her chairship in February, Cheney was censured by the Wyoming GOP for failing to support Trump (Representative Tom Rice of South Carolina faced a comparable backlash for his similar vote). But after a tense leadership retreat at the end of April, Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (who had supported Cheney in February, but was recently caught criticizing her to a reporter with an unexpectedly hot microphone) instigated another attempt at her removal; after only sixteen minutes of debate, Cheney’s position was revoked by an unrecorded voice vote behind closed doors.

Prior to 2021, Liz Cheney had enjoyed relatively consistent political success as the sole representative of Wyoming in the House, routinely winning elections with supermajorities of the vote (her 2020 campaign, for example, saw her win 73% of primary ballots and nearly 70% of the general election). Particularly considering her political pedigree (her father is former Vice President Dick Cheney), it is perhaps unsurprising that Liz Cheney has been frequently mentioned in speculations about the future of the GOP’s leadership. Despite her recent setbacks, Cheney has indicated her plans to fight for her political future in the coming primary election (several additional candidates have already filed to run for the Republican nomination and Trump’s political team has indicated its intent to support one of her challengers).

The question for us to consider here is: what did Liz Cheney do wrong?

On its face, one answer to this question is plain: Cheney failed to show fealty to Donald Trump, the leader of the Republican party. Although once an ally of the former president (and supporting over 90% of his policy positions with her votes), various events during his final months in office — and particularly his instigation of the mob that attacked Congress on January 6th — led Cheney to break from what John Hudak and others have called “the Church of Trump.” Insofar as Trump’s political persona has become a synecdochal representation of the party as a whole, Cheney’s critiques of Trump’s behavior might be seen as critiques of the party itself — certainly by members of the party’s rank and file; consider how one man in Gillette, Wyoming explained his anger at Cheney’s vote to impeach Trump: “’We are very loyal people here,’ said Paul Roberts, 47. ‘We didn’t elect her to vote her conscience.’”

One might, then, be tempted to draw comparisons between the contemporary adulation Donald Trump receives from Republicans and the political theory of philosopher Thomas Hobbes. When Lindsey Graham, the senior senator from South Carolina (who has represented his state in Washington since 1995), states that the Republican party can not “move forward without President Trump,” Graham is evoking an image of Trump as a political figurehead whose authority and power is of supreme importance for the continued functioning of the government — much like Hobbes’ notion of the Leviathan. To Hobbes, the world is a frightening and violent place filled with dangers — he infamously describes life in this so-called State of Nature as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” — and only the strength of an absolute monarch can protect the citizenry and maintain social stability. Certainly, much of Trump’s nationalistic rhetoric, his fear-based politics, and his persistent cultivation of an authoritarian strong-man image over the last half-decade suggest a desire to be seen as a Hobbesian Leviathan (and the acquiescence of many long-standing party members within the GOP to such a vision is telling). By casting doubt on the primacy of the leader, Representative Cheney might be viewed by Republicans as a seditious enemy who needs to be removed from her influential position within the party.

However, this explanation seems incomplete — and not least because of the formal presumption that the United States recognizes no actual king. Although Cheney is one of the only party members to experience official punishment for her conscientious objections to Trumpism, she is not the only influential Republican to criticize Donald Trump. Consider, for example, the former governor of Massachusetts and current senator from Utah Mitt Romney: not only was Romney the sole Republican to vote for Trump’s conviction in both of the president’s Senate trials, but he has repeatedly criticized the former president’s approach to politics and even indicated publicly that he did not vote for Trump in 2020. Nevertheless, Romney has enjoyed relatively consistent support from many of his constituents and managed to avoid a censure vote from the Utah GOP in April (though a few Utah counties have since voted separately for his censure). Arguably, Romney, as a former Republican presidential nominee and long-standing representative of the party on a national scale, is an even bigger threat to Trump the Would-Be Leviathan than Liz Cheney, so why is she in even hotter water?

It might well be thanks to Cheney’s gender. Philosopher Kate Manne has argued that “misogyny” is not merely a matter of women being hated in virtue of their gender, but rather that misogyny manifests when women are systematically mistreated because of social structures that disadvantage them. More specifically, misogyny is “primarily about controlling, policing, punishing, and exiling the “bad” women” who do not conform to the roles expected of them by those in power. Even if Trump is not a full-blown Leviathan, he certainly still wields considerable clout within the GOP: criticizing him, as Cheney has, could easily earn her the label of a “bad” woman who “deserves” to be exiled.

Consider, too, Cheney’s expected replacement as chair of the conference: four-term Representative Elise Stefanik from upstate New York. Although Stefanik’s voting record has been far less aligned with typical Republican positions than Cheney’s, she has been a vocal supporter of Donald Trump for some time. During Trump’s first impeachment trial, Stefanik found the spotlight with her passionate defenses of the accused president and has since continued to consistently back Trump, amplifying his claims about alleged voting irregularities in the 2020 election and voting to reject some of President Joe Biden’s electoral votes. In this way, Stefanik might be understood as someone who is playing the game so as to be included on the GOP/Trump team — she is a “good” woman serving well the interests of the system in which she finds herself (contrast this with Stefanik’s first few years in Congress when she was actually quite critical of Trump). Now, her pro-Trump performances have earned her praise from the former president, even as he has been increasingly critical of Cheney. By speaking her mind and voting her anti-Trump conscience, misogyny demands that Cheney be punished — even by Stefanik, who twice nominated Cheney for the leadership position she is now poised to assume.

The future of the Republican party — and whether the Cheneys/Romneys or Trumps/Stefaniks come to define it — remains to be seen. One thing, though, is certain: the consequences of hyper-partisan political attitudes negatively affect many people (both external and internal to the parties in question) — and women, in particular, bear uniquely potent pressures. When an authoritarian figure demands loyalty above all other virtues (and functionally “cancels” people who choose independence), everybody beneath the Leviathan’s boot loses.