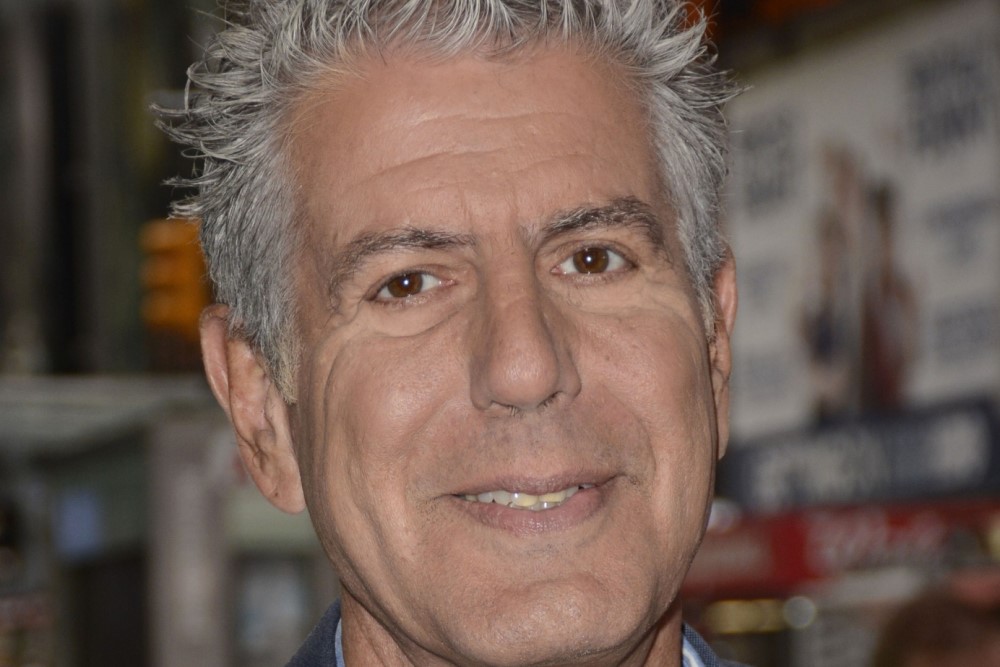

Back in 2021, I wrote an article for The Prindle Post predicting the corrosive effect AI might have on documentary filmmaking. That piece centered around Roadrunner: A Film about Anthony Bourdain, in which an AI deepfake was used to read some of the celebrity chef’s emails posthumously. In that article, I raised three central concerns: (i) whether AI should be used to give voice and body to the dead, (ii) the potential for nefarious actors to use AI to deceive audiences, and (iii) whether AI could accurately communicate the facts of a situation or person.

Since that article’s publication, the danger AI poses to our ability to decipher fact from fiction in all facets of life has only grown, with increasing numbers of people able to produce ever more convincing fakery. And, while apprehensions about this are justifiably focused on the democratic process, with Time noting that “the world is experiencing its first AI elections without adequate protections,” the risk to our faith in documentary filmmaking remains. This is currently being discussed thanks to one of Netflix’s most recent releases — What Jennifer Did.

The documentary focuses on Jennifer Pan, a 24-year-old who, in 2015, was convicted of hiring hitmen to kill her parents (her father survived the attack, but her mother did not) because they disapproved of who she was dating. Pan is now serving a life sentence with the chance of parole after 25 years.

The story itself, as well as the interviews and people featured in it, is true. However, around 28 minutes into the documentary, some photographs which feature prominently on-screen raise doubt about the film’s fidelity to the truth. During a section where a school friend describes Jennifer’s personality — calling her “happy,” “bubbly,” and “outgoing” — we see some pictures of Jennifer smiling and giving the peace sign. These images illustrate how full of life Jenifer could be and draw a contradiction between the happy teen and the murderous adult.

But, these pictures have several hallmarks of being altered or just straight-up forgeries. Jenifer’s fingers are too long, and she doesn’t have the right number of them. She has misshapen facial features and an exceedingly long front tooth. There are weird shapes in the back- and foreground, and her shoulder appears out of joint (you can see the images in question on Futurism, where the story broke). As far as I’m aware, the documentary makers have not responded to requests for comments, but it does appear that, much like in Roadrunner, AI has been used to embellish and create primary sources for storytelling.

Now, this might not strike you as particularly important. After all, the story that What Jennifer Did tells is real. She did pay people to break into her parent’s house to kill them. So what does it matter if, in an attempt to make a more engaging piece of entertainment, a little bit of AI is used to create some still (and rather innocuous) images? It’s not like these images are of her handing over the money or doing things that she might never have done; she’s smiling for the camera in both, something we all do. But I think it does matter, and not simply because it’s a form of deception. It’s an example of AI’s escalating and increasingly transgressive application in documentaries, and particularly here, in documentaries where the interested parties are owed the truth of their lives being told.

In Roadrunner, AI is used to read Bourdain’s emails. This usage is deceptive, but the context in which it is done is not the most troubling that it could be. The chef sadly took his own life. But he was not murdered. He did not read the emails in question, but he did write them. And, while I suspect he would be furious that his voice had been replicated to read his writing, it is not like this recreation existed in isolation from other things he had written and said and did (but, to be clear, I still think it shouldn’t have been done).

In What Jennifer Did, however, we’re not talking about the recreation of a deceased person’s voice. Instead, we’re talking about fabricating images of a killer to portray a sense of humanity. The creative use of text, audio, and image shouldn’t, in itself, cause a massive backlash, as narrative and editing techniques always work towards this goal (indeed, no story is a totally faithful retelling of the facts). But, we must remember that the person to whom the documentary is trying to get us to relate – the person whom the images recreate and give a happy, bubbly, and outgoing demeanor – is someone who tried and, in one case, succeeded in killing her parents. Unlike in Roadrunner, What Jennifer Did uses AI not to give life to the lifeless but to give humanity to someone capable of the inhumane. And this difference matters.

Now, I’m not saying that Jennifer was or is some type of monster devoid of anything resembling humanity. People are capable of utter horrors. But by using AI to generate fake images at the point at which we’re supposed to identify with her, the filmmakers undermine the film’s integrity at a critical juncture. That’s when we’re supposed to think: “She looks like a normal person,” or even, “She looks like me.” But, if I can’t trust the film when it says she was just like any other teen, how can I trust it when it makes more extreme claims? And if a documentary can’t hold its viewer’s trust, with the most basic of things like “what you’re seeing is real,” what hope does it have in fulfilling its goal of education and informing? In short, how can we trust any of this if we can’t trust what we’re being shown?

This makes the usage of AI in What Jennifer Did so egregious. It invites doubt into a circumstance where doubt cannot, should not, be introduced. Jeniffer’s actions had real victims. Let’s not mince our words; she’s a murderer. By using AI to generate images — pictures of a younger version of her as a happy teen — we have reason to doubt the authenticity of everything in the documentary. Her victims deserve better than that, though. If Netflix is going to make documentaries about what is the worst, and in some cases the final, days in someone’s life, they owe those people the courtesy of the truth, even if they think they don’t owe it to the viewers.