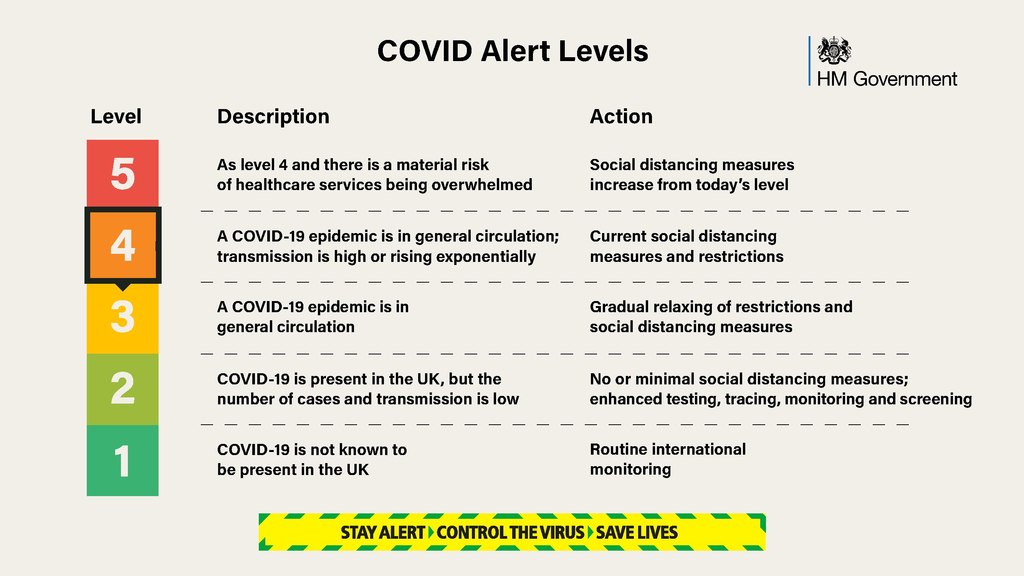

The world has changed a lot since COVID-19 burst onto the scene, upturned our lives, crashed economies, and killed millions. For some, the fear of the disease remains (not unjustly, either). For others, the fact that we went through such a massive event seems nearly unremarkable, or at least not unlike other generational traumas (like the Cold War), and those persons argue that we need to stop focusing on it and move on.

Governments, however, sit in an interesting liminal space between these two poles. On the one hand, they want people to return to work, which many, if not most of us, are. Yet, the lingering effects of the pandemic, direct or indirect, can still be felt throughout the workforce For example, figures recently revealed that the U.K. has record levels of economically inactive people — nearly a quarter of people of working age, a trend that started in the wake of the pandemic. To get economies moving and GDP on the rise then, states want citizens to be as active as possible.

On the other hand, governments cannot ignore the human and economic damage caused by the pandemic, something which, heaven forbid, might happen again. So, they must stick with the pandemic and investigate its emergence and our responses to it to better prevent (or, more realistically, mitigate) such a catastrophe in the future. This is the purpose of the U.K.’s COVID-19 Inquiry, launched in June 2022 by Former Prime Minister Boris Johnson. And it is with Johnson, and specifically his attitude towards the pandemic, that I wish to stay.

Now, for those blessed with memory or ignorance that obscures Johnson from recollection, let me provide the briefest of bios. Boris Johnson was the U.K.’s Prime Minister from 2019 – 2022. During that time, he and his government were hit by multiple scandals including, but by no means limited to, unlawfully proroguing parliament, ignoring a report that the Home Secretary had bullied members of staff, holding parties during the pandemic in contravention to the very laws he put in place, and supporting an MP who Johnson knew had a history of workplace sexual misconduct. It was this last scandal that eventually brought the now disgraced former PM down, with so many members of his party resigning from government that he couldn’t find people to fill any of the key roles. This eventually forced him out of office, but not before attempting a face-saving speech where he’d claim he’d be back (luckily, Johnson hasn’t returned; unluckily, he was followed by the catastrophic Liz Truss).

It is something Johnson reportedly said in December 2020 that I want to consider, however. In his diaries recounting his efforts to counsel the government during the pandemic, the Chief Scientific Advisor at the time, Sir Patrick Vallance, noted that Johnson seemed incapable of comprehending the sheer scale of the danger the emergency posed. Moreover, the PM appeared fascinated with older people accepting their fate for the greater good. In other words, he thought that those of an elderly disposition should die so that the country wouldn’t be impacted as hard. This was a position not only he held, but so did others supporting the PM (although few would admit it now). This stance is alluded to in WhatsApp messages from the PM to others, where he reflects repeatedly upon a correlation between fatality rates and age.

In short, then, it seems Johnson, the man in charge of the U.K.’s response to the pandemic, held a quasi-Darwinian stance to resource allocation and policy: If you’re too old, and thus too weak, to fight the disease, tough luck. You’ve had your life; accept your fate, and let the young, who can typically survive the infection, carry on.

This is an undoubtedly callous position to hold. Yet, callousness alone isn’t a valid reason to reject it. After all, if one can make an argument that the old should accept one’s fate, that they have lived a life and so expecting younger people and the country to sacrifice for them is unreasonable, then there might be something to the position even though it is, much like the man himself, detestable. And, as I’m sure you’ve probably guessed, there is such an argument—the fair innings argument (FIA).

The FIA is, on the face of it and in the abstract, one that many of us would find appealing. As conceptualized by John Harris:

The [FIA] takes the view that there is some span of years that we consider a reasonable life… Let’s say that a fair share of life is the traditional three score and ten, seventy years. Anyone who does not reach 70 suffers, on this view, the injustice of being cut off in their prime. They have missed out on a reasonable share of life; they have been short-changed. Those, however, who do make 70 suffer no such injustice, they have not lost out but rather must consider any additional years a sort of bonus beyond that which could reasonably be hoped for. The fair innings argument requires that everyone be given an equal chance… to reach the appropriate threshold but, having reached it, they have received their entitlement. The rest of their life is the sort of bonus which may be cancelled when this is necessary to help others reach the threshold.

Thus, it is an argument grounded in fairness and justice. Each year is a unit of value which we accrue as we age. The elderly are more prosperous than the young regarding their life experience. And so, when there is a clash of interests between the young and old, between those who have lived a life and those who have not, it seems not entirely unfair to expect the former to make a sacrifice to benefit the younger. They’ve lived a life, and they should pay that forward where necessary.

Now, there are problems with the argument, not least of which is where one draws the line between fairness and unfairness, between too young to die and too old to live. But, in the context of COVID-19 and in light of Johnson’s multiple professional indiscretions, I think the bigger picture here is that he discounted the inhumanity of his position and, indirectly, of the fair innings argument.

No matter which way you slice it, the argument is cold. It boils human experience down to a base numerical value and disregards experiential or relational qualities. All that matters is that the old have lived a life. The quality of that life? Well, that’s of no concern here. The human factor involved, the all-consuming fear of dying? Not Johnson’s concern. And this is what aggravates me so here. Johnson reduced human life to a numbers game, something he could track and try to balance on a spreadsheet. I would say it betrays a sense of superiority and control — that it reveals a self-perception of himself as someone playing a strategy game, directing his units in battle, and trying to balance an economy for no other reason than the fun of it — but that would be a lie. We already knew this about him. After all, this is the man who, when asked as a boy what he wanted to be when he was older, said, “World king.”

It is this mentality — that life is reducible to a numerical value — that irks me so much. During the pandemic and the countless other tragedies that have occurred over our lifetimes, we saw that suffering, despair, fear, and loneliness are not problems to be solved by sacrificing those who experience them the most acutely. They are failures on our part as a society to empathize with those who go through such hardships.

Johnson forgot (and never appreciated) this, and I worry that if the FIA gains traction, we may all do the same.