Stealing money seems wrong. Speeding in a car seems wrong. Even lying on your tax return seems wrong. But is it always wrong to break the law?

Activists for women’s suffrage illegally disrupted Parliament, broke windows, and slashed tires. Gandhi led tens of thousands to the Arabian Sea to illegally gather salt in protest of the heavy tax levied on salt by British law. Rosa Parks illegally sat in the section of the bus reserved for whites under segregation. Edward Snowden illegally handed thousands of classified documents to journalists, revealing the massive surveillance program the United States government was operating. In recent days, almost 2,000 Russians have been arrested for illegally assembling to protest the war in Ukraine.

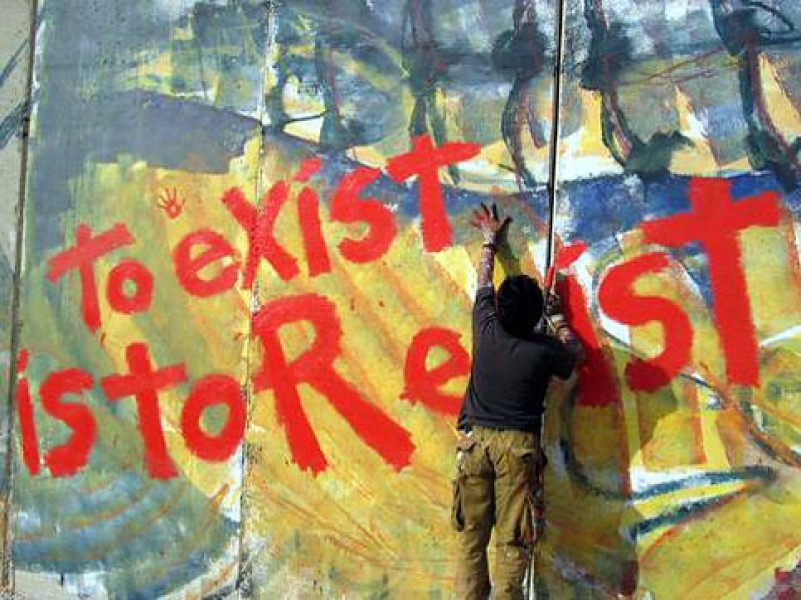

These are all examples of civil disobedience — breaking the law to protest perceived injustice. And I suspect the chances are high that you think at least some of them were justified, moral acts.

Now that it is coming to a close, it’s a good time to ask: was the “Freedom Convoy” that grabbed headlines for so many weeks another example of civil disobedience? Or was it something else?

The philosopher John Rawls thought that civil disobedience was a public, non-violent, conscientious yet political act that was contrary to the law, aimed at bringing about a change in law, or fixing an existing injustice. There’s a lot in that characterization.

What did he mean that it is “public”? Civil disobedience is, fundamentally, an act of communication, “an expression of profound and conscientious political conviction.” The Freedom Convoy protesters were certainly seeking to communicate to the public and those in power that there is an injustice that needs to be rectified. The movement was ideologically diverse and perhaps unsavory in parts, but its core message was protesting vaccine mandates and vaccine passports for truckers crossing the U.S. border. The perspective of the protesters was that these laws were unjust — that the government had overreached and infringed on Canadians’ rightful liberties. They were trying to bring the attention of the public and pressure politicians to change the law. I’m not going to try to figure out if the protesters were right or wrong about these laws being unjust. Whatever the case, it seems clear that their protest was a public act. It also seems clear that it was aimed at bringing attention to a perceived breach of justice, and bringing about a change in the law to rectify the perceived injustice.

Rawls also claimed that civil disobedience is non-violent. This distinguishes it from more extreme forms of political action such as militant action and terrorism. The reason civil disobedience ought to be non-violent, Rawls thought, is connected to its function as an act of public communication. If violence occurs, it is likely to distract from the intended message and discredit the movement.

These ideas are echoes of Martin Luther King Jr.’s moving “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” in which the civil rights leader responds to the condemnation of his non-violent but illegal marches against racism and segregation. It is clear that King, like Rawls, sees non-violence as vital to civil disobedience’s power to rectify injustice. The civil rights protestors had workshops on non-violence, and asked themselves, before marching “Are you able to accept blows without retaliating?” “Are you able to endure the ordeal of jail?” Only those who answered affirmatively were permitted to march.

Finally, Rawls thought civil disobedience was contrary to the law, but still “in fidelity” to the law, still conscientious. This might sound paradoxical, and it’s a tension MLK Jr. confronted. He wrote,

Isn’t negotiation a better path? [Civil disobedience] seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth.

Those who commit civil disobedience intentionally break the law, but they do so purely to draw attention to the cause of pursuing justice. They peacefully accept being arrested and enduring whatever legal punishments they receive. This demonstration of respect for the legal system is also crucial to the communicative function of civil disobedience. The protestors, in order to change it, must show that they accept the existence of the legal and political system. They want to improve it, not to overthrow it. For this reason, Howard Zinn suggests that “Protest beyond the law is not a departure from democracy; It is absolutely essential to it.”

Once again, the Freedom Convoy seems to have largely demonstrated fidelity to the law, even while acting contrary to the law. While illegally blocking the bridge linking the U.S. and Canada, at least 100 Freedom Convoy protestors were peacefully arrested without resistance.

All in all, the Freedom Convoy does qualify as civil disobedience, at least according to Rawls’ characterization. But not all civil disobedience is morally acceptable. So the next question to ask is this: was the civil disobedience of the Freedom Convoy moral?

Once again, we can get some help with this question from Rawls. He provides three criteria that need to be met for civil disobedience to be moral.

The first is that it is sincere. Those who are breaking the law must truly believe that the policies or laws they are seeking to change are unjust. They cannot be using the cause as an excuse to break the law, or the cause as a cudgel to beat their political opponents. It’s much harder to say whether this standard was met by the Freedom Convoy as a whole. Many protestors appear to have been sincere, while others arguably used the movement as a partisan opportunity to push conspiracy theories or put political pressure on the politicians they already opposed.

The next standard that Rawls claims needs to be met for civil disobedience to be moral is that the challenge must be well-founded. The injustice that is being protested must be a genuine, serious breach of justice, of security, social welfare, rights, democracy, and so on. It must be a cause worth breaking the law for. Were the vaccine mandates and passports a breach of basic rights or a sensible health measure? This is a hard question, and a lot of ink has already been spilled (or keyboards hammered) answering it. I am sure you have your own views.

Rawls’ final criterion that must be met for civil disobedience to be moral is that it must have good enough consequences. It cannot, for example, be justified to commit murder in an attempt to condemn or change overly harsh legal penalties for murder. There must be a good balance between the benefit of rectifying injustice and any harm generated by the law being broken in protest. The disruption to ordinary citizens’ lives in Ottawa was fairly profound, and this can only be justified if the protest achieves something even more valuable than that which is destroyed.

This last criterion means that, in many cases, legal forms of protest should be favored over civil disobedience, as the former tends to generate smaller costs for both the protestors and society at large. Even so, civil disobedience can still be justified as a last resort. MLK Jr. found it important that his own civil disobedience was the last resort. “It is unfortunate that [illegal] demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham,” he wrote, “but it is even more unfortunate that the city’s white power structure led the Negro community with no alternative.”

Was the Freedom Convoy’s law-breaking a last resort? It’s a difficult question. There had been rising dissent against the coronavirus restrictions since the first lockdown of 2020 but few reductions in restrictions, which might suggest to some that the legal avenues for change had been exhausted and failed. But to others, this only shows that these legal avenues had never been fully explored and that the Freedom Convoy caused needless disruption and suffering and was never the last resort.

If you are left feeling frustrated that philosophy refuses to deliver any clear answers, I acknowledge the point. But philosophy can at least give us the tools to think about things more clearly; Rawls’s framework for evaluating civil disobedience may not be able to tell us if the Freedom Convoy was right or moral, but it does at least help us to focus on the right questions in trying to find an answer.