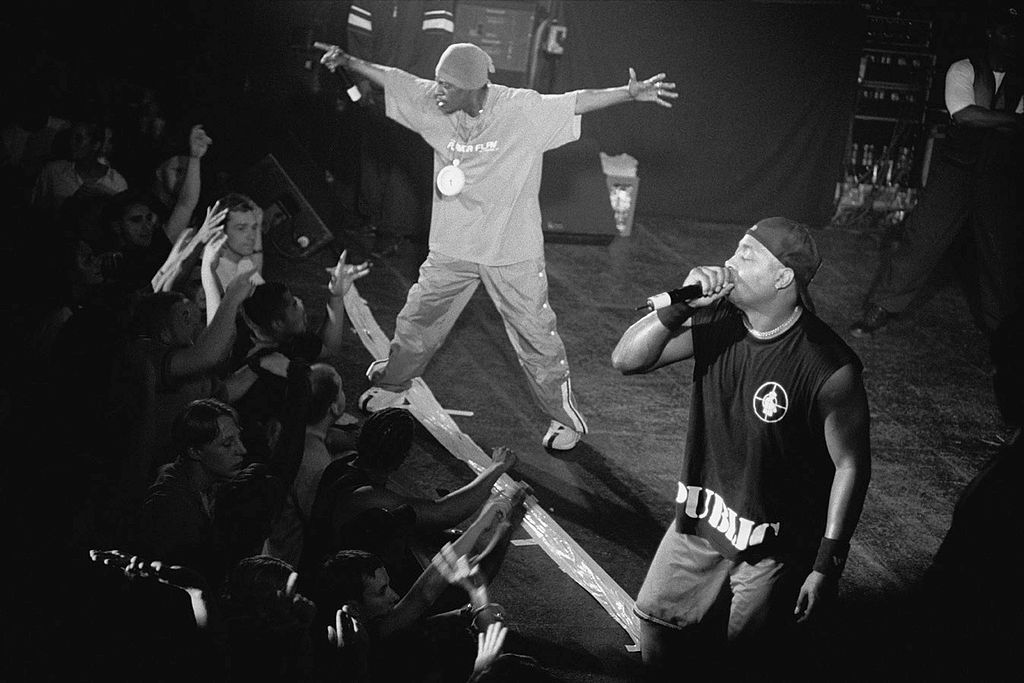

Hip-hop music began in the 1980s, and was primarily a means for African American communities to express commentary and frustration related to politics, discrimination, and common struggles often related to race relations. Crucially, music was being used to give voice to a people that has traditionally been suppressed or discounted because of the effects of systemic racism in the American political institution. One of the most significant groups to pioneer this genre was Public Enemy, whose music focused largely on sociopolitical commentary.

Women’s Resilience and Post-Feminist Sexism

This post originally appeared November 10, 2015.

In 1977, punk pioneer Poly Styrene used loud, screamed, overdriven vocals to revolt against the stereotype that “little girls should be seen and not heard.” In the 1990s, the riot grrrl bands she inspired used similar strategies to shout “revolution girl style now!” In 2014, Rebecca Solnit, who coined the term “mansplaining,” argued that year was “a year of mounting refusal to be silent…a loud, discordant, and maybe transformative” time because the “strong individual voices and the great collective roar of social media” meant that “women are coming out of a silence that lasted so long no one can name a beginning for it.” Women, in other words, could most certainly be heard, and people were finally paying attention to those screams.

Is society’s ability to hear and celebrate women’s noisy feminist voices really evidence of progress, as Solnit claims? Or is loud, noisy “feminist” voice just a different type of oppressive stereotype we expect women to embody?

The short answer is: no to the first question, and yes to the second. The longer answer is that society’s investment in the concept and practice of resilience has some very specific implications for women. Last month I wrote about resilience discourse in general, and argued that it reproduces the relations of domination and inequality that it claims to solve. Here, I want to focus on how individual women’s resilience contributes to institutionalized sexism and racism. We expect women to perform a specific kind of resilience: they must loudly and spectacularly demonstrate that they have overcome patriarchal oppression. Noisy feminism is both a new gender norm for women to embody and a tool white supremacy uses to scapegoat non-white men for lingering sexism.

Traditionally, (white) women were supposed to be passive, silent, and fragile–princesses to be rescued, damsels in distress. Resilience has replaced these older stereotypes; as photographer Kate Parker puts it, “strong is the new pretty.” We now expect individual women to overcome the damage wrought by traditional femininity (negative body image, objectification, sexual assault and/or domestic violence, silencing, etc.): they need to “lean in” and be tough, be “all about that bass,” and so on. Resilience still requires women to be hurt by the same old sexism while also creating a new kind of sexism on top of it. This new sexism has a few interwoven layers: (1) it makes women responsible for fixing sexism, thus maintaining the gendered division of labor that has women cleaning up after everyone else’s mess; (2) treating the negative effects of sexism as individual women’s failure, not society’s failure, it hides the fact of ongoing social injustice behind the veneer of feminist victory; (3) it replaces what gender studies scholars call the virgin/whore dichotomy with the opposition between resilience and lazy backwardsness so that women who don’t appear to be resilient are seen as both abnormally gendered and sexually deviant; (4) it instrumentalizes women, using them as tools to cut the post-racial color line and hide white supremacy behind the veneer of racial diversity.

Though the music videos for both Rihanna’s “Bitch Better Have My Money” (BBHMM) and Beyonce (feat. Lady Gaga)’s “Video Phone” tell stories about women conquering male dominance, the differences between the videos and reactions to them clarify how (3) and especially (4) work. In each video, the main woman character(s) executes a man that has harmed her. Beyonce and Gaga shoot arrows into camera-headed men, who symbolize the male gaze that objectifies women and reduces them just to their bodies. Rihanna butchers her accountant who embezzled from her, continuing a long line of what Doreen St. Felix identifies as gendered “Love & Theft” from black women musicians. The plot is effectively the same, except for one major difference: in “Video Phone,” Beyonce kills a black man; in BBHMM, Rihanna kills a white one. Beyonce’s performance appears resiliently feminist: she overcomes the male gaze that would otherwise objectify her. Rihanna’s performance, however, was widely critiqued as un-feminist. Though most critics said BBHMM was misogynist because Rihanna’s character kidnapped the accountant’s woman partner, that’s not why it felt un-feminist. Her performance felt un-feminist because it wasn’t properly resilient. Women’s resilience is supposed to point the finger at men of color, especially black men, as exceptionally backwards, misogynist, and incapable of evolving with the times. For example, as NPR reported, the Hollaback! Project’s 2014 video “10 Hours of Walking In NYC As A Woman” edited out all the white men so that black and Latino men appear solely responsible for street harassment. Similarly, non-Western men of color are often portrayed as backwards, regressive remnants of the misogynist attitudes and behaviors that Americans have evolved beyond. BBHMM doesn’t do this: it points the finger squarely at an extremely wealthy white man and blames him for still practicing the old-school (and racist) sexism that he and society are supposed to have overcome. Women’s resilience is supposed to show that some group of non-white men is incapable of overcoming old-school misogyny, and are thus unfit for inclusion in our post-feminist, post-racial, multicultural society–this is how resilience discourse instrumentalizes women in the name of white supremacy. And women who deal with sexism in ways that doesn’t cut a line between regressive non-white men and progressive, diverse society–they’re not resilient. Because resilience is the definitive feature of contemporary femininity, non-resilient women appear deficiently feminine, like they’re not “really” women.

Resilience, as I argued in my last post, isn’t just coping: it’s a way of reproducing hegemonic social institutions. Women’s resilience reproduces sexism and racism in the particular forms that work best with 21st century technologies, international and domestic politics, and media. And that’s why it’s something we expect women to practice. Women have to be resilient, because their resilience is key to the kinds of sexism and racism that hide behind the appearance of post-feminist, post-race multiculturalism. Resilient women aren’t liberated from narrow stereotypes; resilience is just a new stereotype they’re expected to fit.

“Okay Ladies, Now Let’s Get in Formation”

The Super Bowl happened last month, but the media still has not quieted down over Beyoncé’s half time performance, particularly the debut of her new song, “Formation.” For those who haven’t seen the music video or her Super Bowl performance, it is unlike anything the singer has done to date. It was culturally provocative, emotional, highly stimulating and an reminder of where Beyoncé came from. From Beyonce on top of a sinking police car in what seems to be New Orleans to her riding around in an old convertable with her hair in braids, the images leave little doubt in the viewers mind that Beyonce is black.

In the music video, released a day before her Super Bowl performance, Beyonce takes on all African-American stereotypes and does so in her own way. Beyoncé and Jay- Z, her husband, have been publicly quiet on the racial conflicts of the past few years, including the Black Lives Matter movement. But the couple has taken a more public role in racial dialogues. Beyonce’s “Formation” in combination with Jay-Z’s business Tidal donating $1.5 million to the Black Lives Matter program makes their position on these issues fairly clear.

Continue reading ““Okay Ladies, Now Let’s Get in Formation””