Many people don’t have much occasion to observe racism in the United States. This means that, for some, knowledge about the topic can only come in the form of testimony. Most of the things we know, we come to know not by investigating the matter personally, but instead on the basis of what we’ve been told by others. Human beings encounter all sorts of hurdles when it comes to attaining belief through testimony. Consider, for example, the challenges our country has faced when it comes to controlling the pandemic. The testimony and advice of experts in infectious disease are often tossed aside and even vilified in favor of instead accepting the viewpoints and advice from people on YouTube telling people what they want to hear.

This happens often when it comes to discussions of race. From the perspective of many, racism is the stuff of history books. Implementation of racist policies is the kind of thing that it would only be possible to observe in a black and white photograph; racism ended with the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. There is already a strong tendency to engage in confirmation bias when it comes to this issue — people are inclined to believe that racism ended years ago, so they are resistant and often even offended when presented with testimonial evidence to the contrary. People are also inclined to seek out others who agree with their position, especially if those people are Black. As a result, even though the views of these individuals are not the consensus view, the fact that they are willing to articulate the idea that the country is not systemically racist makes these individuals tremendously popular with people who were inclined to believe them before they ever opened their mouths.

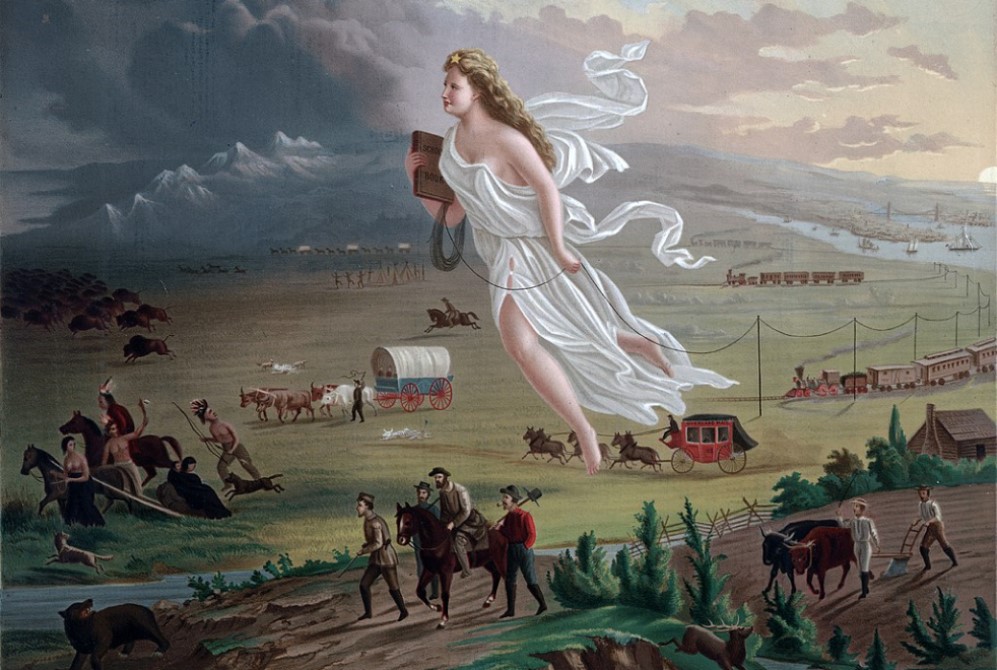

Listening to testimonial evidence can also be challenging for people because learning about our country’s racist past and about how that racism, present in all of our institutions, has not been completely eliminated in the course of fewer than 70 years, seems to conflict with their desire to be patriotic. For some, patriotism consists in loyalty, love, and pride for one’s country. If we are unwilling to accept American exceptionalism in all of its forms, how can we count ourselves as patriots?

In response to these concerns, many argue that blind patriotism is nothing more than the acceptance of propaganda. Defenders of such patriotism encourage people not to read books like Ibram X. Kendi’s How to be an Anti-racist or Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, claiming that this work is “liberal brainwashing.” Book banning, either implemented by public policy or strongly encouraged by public sentiment has occurred so often and so nefariously that if one finds oneself on that side of the issue, there is good inductive evidence that one is on the wrong side of history. Responsible members of a community, members that want their country to be the best place it can be, should be willing to think critically about various positions, to engage and respond to them rather than to simply avoid them because they’ve been told that they are “unpatriotic.” Our country has such a problematic history when it comes to listening to Black voices, that when we’re being told we shouldn’t listen to Black accounts of Black history, our propaganda sensors should be on high alert.

Still others argue that projects that attempt to understand the full effects of racism, slavery, and segregation are counterproductive — they only lead to tribalism. We should relegate discussions of race to the past and move forward into a post-racial world with a commitment to unity and equality. In response to this, people argue that to tell a group of people that we should just abandon a thoroughgoing investigation into the history of their ancestors because engaging in such an inquiry causes too much division is itself a racist idea — one that defenders of the status quo have been articulating for centuries.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. beautifully articulates the value of understanding Black history in a passage from The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.:

Even the Negroes’ contribution to the music of America is sometimes overlooked in astonishing ways. In 1965 my oldest son and daughter entered an integrated school in Atlanta. A few months later my wife and I were invited to attend a program entitled “Music that has made America great.” As the evening unfolded, we listened to the folk songs and melodies of the various immigrant groups. We were certain that the program would end with the most original of all American music, the Negro spiritual. But we were mistaken. Instead, all the students, including our children, ended the program by singing “Dixie.” As we rose to leave the hall, my wife and I looked at each other with a combination of indignation and amazement. All the students, black and white, all the parents present that night, and all the faculty members had been victimized by just another expression of America’s penchant for ignoring the Negro, making him invisible and making his contributions insignificant. I wept within that night. I wept for my children and all black children who have been denied a knowledge of their heritage; I wept for all white children, who, through daily miseducation, are taught that the Negro is an irrelevant entity in American society; I wept for all the white parents and teachers who are forced to overlook the fact that the wealth of cultural and technological progress in America is a result of the commonwealth of inpouring contributions.

Understanding the history of our people, all of them, fully and truthfully, is valuable for its own sake. It is also valuable for our actions going forward. We can’t understand who we are without understanding who we’ve been, and without understanding who we’ve been, we can’t construct a blueprint for who we want to be as a nation.

Originally published on February 24th, 2021