After a year of isolation for most everyone around the world, there is hope that we will get back to a more normal existence thanks to the continued roll-out of vaccines. Traditions that were impossible with coronavirus might now be making a comeback, and this includes the internationally-beloved Olympic Games. While the Tokyo 2021 Olympics are desperately trying to make the show go on while Japan struggles with a rise in infections, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) is already facing challenges to the 2022 Winter Games in Beijing. Although the city won the bid to host the games in 2015 there has been an intense wave of criticism with China’s recent actions towards their own people. When Beijing was one of two countries on the ticket to win the bid for next years’ Olympics, the IOC passed reforms aimed at protecting human rights in the host countries. This was after the Sochi 2014 Olympics where there were mass violations of human rights, especially against migrant workers who came to Sochi to help build the facilities for the Olympics. In an attempt to prevent a similar disaster in the future, the IOC passed a number of reforms. Thus far, however, these measures have proven ineffective in preventing human rights violations. Despite China currently committing atrocities against their own citizens, the IOC continues to support them as the host country.

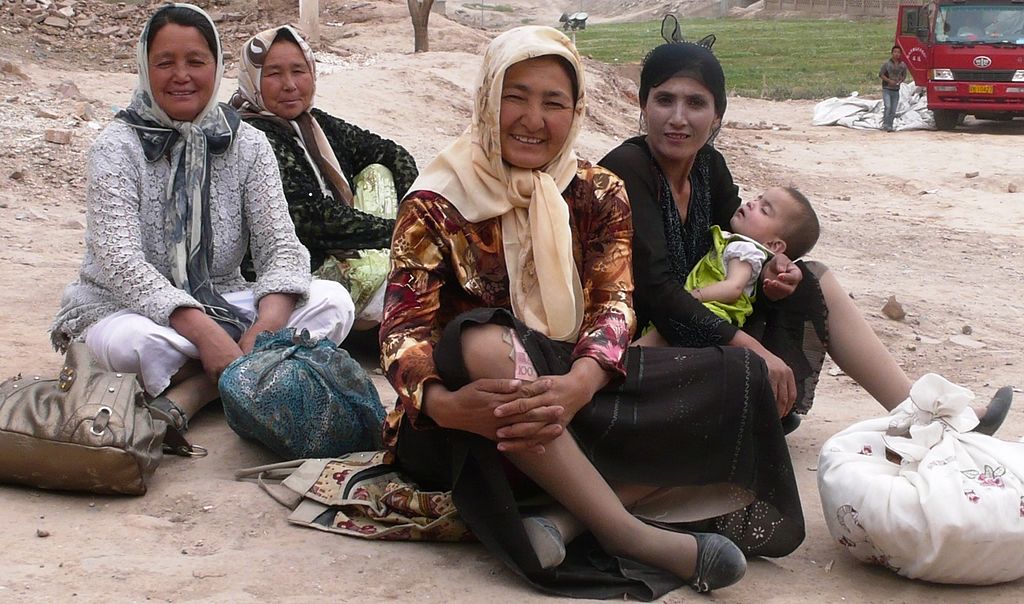

Both the Trump and Biden administrations have characterized China’s actions against the Uyghur population in the Xinjiang region as “genocide.” Since 2019, over one million Uyghurs have been held in “re-education” camps, which are essentially forced assimilation camps where there have been reports of physical abuse, torture, and forced sterilizations. China has denied these allegations and instead claimed that the camps teach job skills as well as the Chinese language. Reports, however, indicate that the Uyghur population, a minority ethnic group, is under continued attack by the Chinese government. These actions represent a clear violation of the reforms the IOC passed in 2015.

Additionally, the government in Beijing has focused their authoritarian energy on Hong Kong, a region that traditionally enjoyed a democratic-like leadership because of former British rule. Recently, that system has essentially collapsed as the government has passed laws placing all the political power of Hong Kong firmly back in the hands of the Chinese Communist Party. This has led to arrests of pro-democracy leaders and human rights activists. Those who escaped are now hiding in exile. As another component of the government’s desire to see a completely unified China, the central government might make Taiwan, who considers itself independent from China, it’s next target. In addition, the Chinese government continues its political control over Tibet, despite the decades-long movement for a free Tibet. Taken together, there is overwhelming evidence that China is currently violating, and will continue to violate, the rights of those they don’t see as fully pro-China.

This situation makes the IOC’s continued support of the 2022 Winter Games in Beijing increasingly difficult to justify. Already, over 180 organizations have called for a boycott. In response, the president of the IOC, Thomas Bach, has insisted that the IOC must remain neutral. This position should perhaps not come as a surprise as the IOC allowed for Nazi Germany to hold the 1936 Olympics, when their anti-semitic policies were well-known around the world. The Nazi regime ensured visitors would receive a picture-perfect look of Germany, one where everyone was welcomed and accepted — a very far cry from the reality. Germany played the part so well that the Games helped legitimize the Nazi regime and earn appeasement from the rest of the world. Eleven Olympic athletes would die in the Holocaust just a few years later. While the Berlin Games were decades ago, the IOC appears to still not have learned their dangerous lesson and recognized the legitimizing power that the Olympics can bring to a country actively violating the rights of millions of people. This power makes it impossible for the IOC to be truly “neutral” in these violations; refusing to move the Olympic venue makes them complicit in the ongoing violence against people in China.

The decision to hold the games in Beijing is in direct opposition to the spirit and mission of the IOC. By their very own definition, Olympism represents a“philosophy of life” for the Olympics which seeks “respect for universal fundamental ethical principles.” That vision also consists of “building a better world through sport.” While these inspirational statements gesture at universal values and global commitments, the committee’s actions look very different. Besides refusing to move the location of the 2022 Olympics, the IOC has also urged countries not to protest these games on the grounds that such demonstrations are not effective in changing policy. While the IOC claims they are fully supportive of freedom of expression, they continue to uphold Rule 50, which is meant to “keep the field of play, Olympic village and the podium neutral.” In reality, this measure merely bars athletes from expressing dissent.

When pressed to draw lines, the committee has reflexively responded that no country should be quick to cast the first stone: “where would you celebrate the games if you take that attitude?” Such deflections make a darker point: while countries like Britain and the U.S. chose to confront Nazi extremism, both have a violent past of colonization and slavery of their own to reckon with. Countries around the world have their own histories, current realities, and potential futures of human rights conflicts. It might be nearly impossible to find a country completely free of blame.

But this does not mean that we must stand idly by. We should instead recognize that it is impossible to remain neutral in today’s world. While sports may be a cathartic and temporary relief from the stress of reality for a lot of people, it is a true privilege to be able to enjoy that relief. There are too many lives, cultures, and countries at risk for the IOC to ignore China’s treatment of its citizens and behavior toward its neighbors. If the committee truly wants to live up to their mission of creating a better world through sport, then they need to acknowledge the lived realities of people being silenced and abused around the world and recognize the impact the Games have in legitimizing those actions and hiding that abuse.