“I’ve been charged with a crime so heinous that busting me for possession of marijuana on federal property would be like charging Hitler with loitering and a multinational company like British Petroleum with littering after fifty years of exploding refineries, toxic spills and emissions, and a shamelessly disingenuous advertising campaign.”

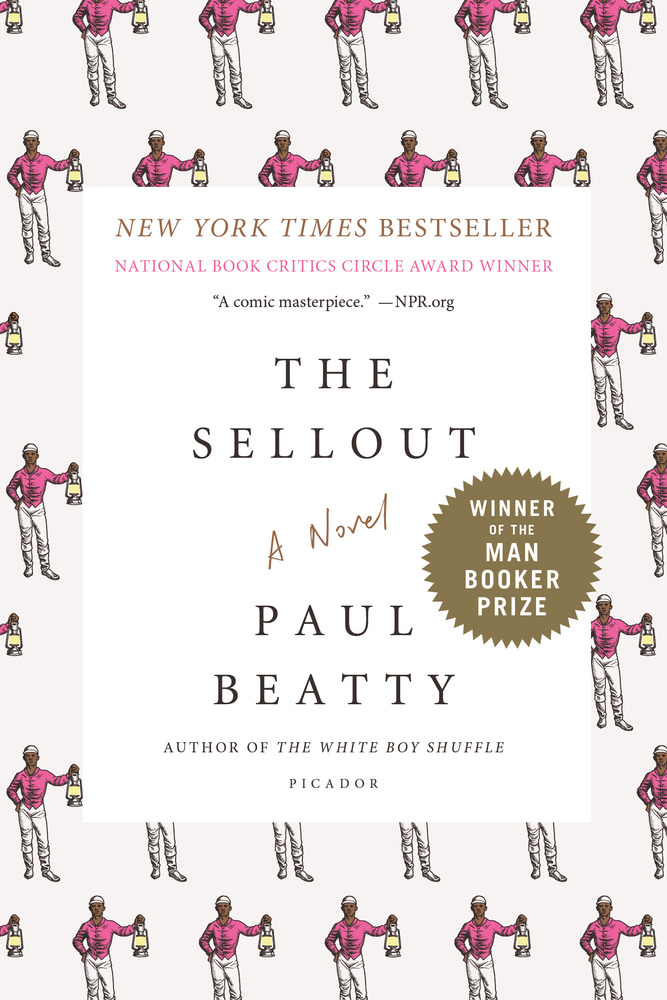

The criminal in question is the narrator of Paul Beatty’s novel, “The Sellout,” who is sitting in the United States Supreme Court, reflecting on the actions that have landed him there, all whilst preparing a bowl of marijuana, which he will proceed to smoke then and there. What is he charged with? The outlandish charges of owning a slave and segregating a public school—charges that he is actually guilty of committing. Told in reverse chronology, the story is grounded by its setting, the fictional ghetto of Dickens in the outskirts of Los Angeles, which happens to have been recently removed from the map of California: vanished, as if it was never there. The novel follows the narrator’s enactment and plotting of his “crimes” as a way to reassert Dickens, its inhabitants, and put it back on the map.