China is pushing for the use of new textbooks, textbooks which will deny that Hong Kong was ever a British colony. The textbooks, which are in the process of being reviewed for approval by teachers, principles, and others affiliated with Hong Kong Bureau of education, would be implemented as curriculum this fall if approved.

These books contain a new narrative about British occupation of Hong Kong, a narrative that will rewrite the previous story that Hong Kong was “lawfully” occupied as a British colony until 1997. The new narrative maintains that Hong Kong was never a British colony and was instead always a part of China. The New York Times, which reviewed teachers’ editions of the new textbooks, quotes the following excerpt: “The British aggression violated the principles of international law so its occupation of Hong Kong region should not have been recognized as lawful.”

These revisions have been in the making for some time and have been roundly criticized by the Professional Teachers’ Union in Hong Kong as “political censorship.” The Bureau, however, rejoined that the changes will “help students develop positive values.”

This push for a new narrative generates a crucial moment for pro-democracy advocates inside and out of China.

One desired effect of this new narrative is that Hong Kong has never been apart from China, so there is no historical basis on which to claim that Hong Kong should continue to be independently and democratically run.

This isn’t the case, however, and would renege on an historic obligation. As Tiffany May writes for The New York Times, “Under the terms of the 1997 handover negotiated with Britain, China had agreed that the social and economic systems of the territory would remain unchanged for 50 years after resuming sovereignty.” Another desired effect of the narrative is that the future generation will be raised patriotic, loyal to China. Indeed, to enforce such “positive values,” students (potentially as young as kindergarteners) will be taught of a new law that permits authorities to deliver prison sentences to those who oppose Beijing.

There are several issues at stake with the question of whether China (that is, Beijing) should rewrite Hong Kong’s history.

In general, to discuss whether something morally should or ought to happen, there is a first question of whether something is morally permissible. If some action isn’t morally permissible, then we ought not to do it; however, even though an action is morally permissible, it does not follow that we ought to do the action. For example, if we conclude that limiting free speech is morally permissible in a certain circumstance, it doesn’t necessarily follow that we ought to limit free speech in that circumstance. Of course, if something ought to happen, this presupposes and requires that whatever ought to happen is morally permissible.

In asking particularly whether Beijing should re-write Hong Kong’s history, one relevant question is whether there are any permissible limitations of freedom of speech, and if so, whether this case is justified.

Part of the new laws permit severe punishment for criticism of or dissent from Beijing. Some in favor of the new laws and textbooks have argued that freedom comes with certain obligations and responsibilities, such as the primary obligation to one’s country. Those in opposition might argue that, while there are certain obligations to one country, these obligations are not relevant in this case. For the obligation to support one’s country is not exclusive of criticizing its present political/societal/economic structure. In fact, criticism might be a sign of an individual’s loyalty in that the individual may desire to change the present situation for the better. In terms of permissibility, then, a special obligation to a nation does not make it impermissible to critique that nation. Indeed, the opposite seems to be the case.

Closely related to the topic of free speech is the question of whether limiting freedom of thought is ever permissible. The issues of freedom of speech and thought certainly overlap: the latter necessarily affects the ability to speak on certain topics, and the former would inevitably affect the ability to think on certain topics. And the revision of textbooks, including the elimination of information and not solely the addition of a perspective, seems to classify at least as a limitation on thought.

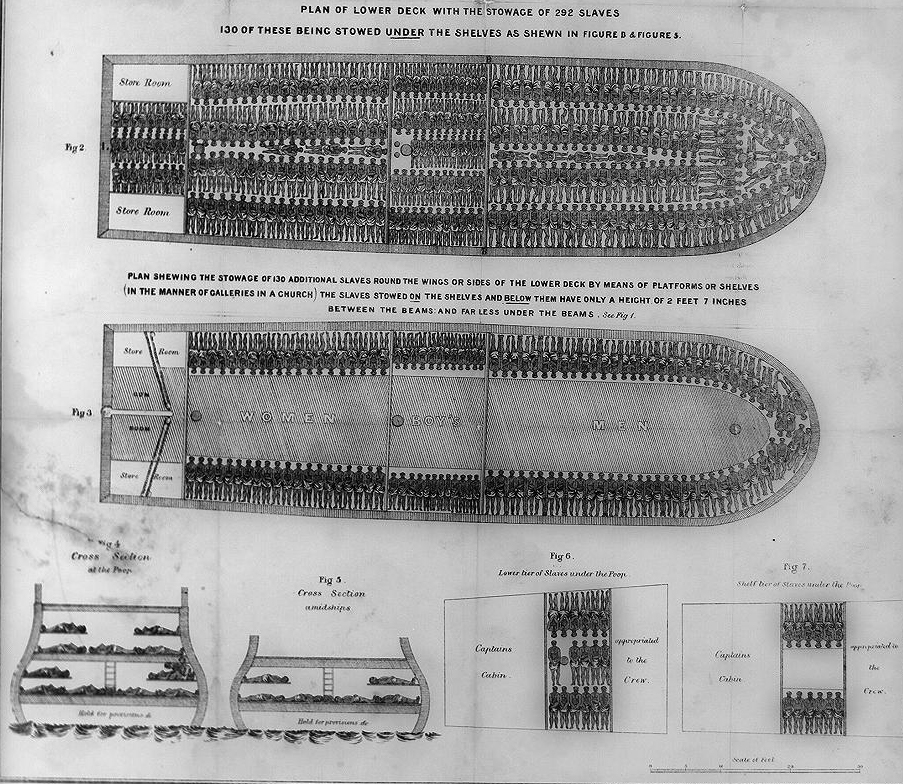

As George Orwell’s novel 1984 has instructed us, the revision of history practically inhibits the future generations (and perhaps present generations) from discussing and knowing history. It is unclear whether this is ever permissible, though it clearly is impermissible in the case that it is factually inaccurate. In the case of Beijing denying Hong Kong’s former status as a colony, this certainly seems to be the case. Of course, it is another matter whether it was morally correct for Britain to have occupied Hong Kong.

While I only suggested some provisional answers to the above questions, it is imperative to answer these questions to understand some of the relevant moral landscape in rewriting history.