On February 24, the New York City Police Department employed a robot “dog” to aid with an investigation of a home break in. This is not the first time that police departments have used robots to aid in responding to criminal activity. However this robot, produced by Boston Dynamics, and affectionately named “Spot,” drew the attention of the general public after New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tweeted a critique of the decision to invest money in this type of policing technology. While Digidog’s main purpose is to increase the safety for both officers and suspects during criminal investigations, some are concerned that the implementation of this type of technology sets a bad precedent, contributes to police surveillance, and diverts resources away from more deserving causes.

Is employing surveillance technologies like Digidog inherently bad? Is it ever okay to monitor citizens without their consent? And which methods should we prioritize when seeking to prevent or respond to crime?

In the United States, an estimated 50 million surveillance cameras watch us, many escaping out notice. The use of these surveillance cameras, formally called Closed Circuit TV’s (CCTVs), have dramatically expanded due to the interest in limiting crime in or around private property. Law enforcement often rely on video surveillance in order to identify potential suspects, and prosecutors may use this footage as evidence during conviction. However, there has been some debate about whether or not the proliferation of CCTV’s has really led to less crime, either through deterrence or through successful identification and capture. This lack of demonstrable proof of positive effect is especially concerning given the pushback against this type of surveillance as potentially violating individuals’ privacy. In a 2015 study by Pew Research Center, 90% of Americans ranked “not having someone watch you or listen to you without your permission” as very important or somewhat important. In a follow-up question, 2/3 of respondents ranked “being able to go around in public without always being identified” as important. Considering the clear importance of privacy to many Americans, increased surveillance might be considered a fundamental infringement on what many see as their right to privacy.

Digidog is a police surveillance tool. Equipped with a camera and GPS, the robot dog is capable of allowing officers to monitor dangerous situations without risking their lives. However, many are skeptical that Digidog’s use will be limited only to responding to crime and could soon instead become a tool to patrol the streets. In one particularly alarming example, an MSCHF Product Studio armed their robot dog with a paintball gun and demonstrated how easy it was to shoot the gun from a remote location. If police departments began arming these robot dogs, the potential for violence and brutality stands to increase. As yet, these uses have not been explicitly suggested by any law enforcement agency, and defenders of Digidog point to its limitations, such as its maximum travel speed, usage in many fields other than policing, and its lack of covert design. These features suggest that Digidog is not yet the powerful tool to patrol or surveil the general public that critics fear.

In terms of Digidog as an investment to combat crime, is it an unethical diversion of money, as Congresswoman Ocasio-Cortez has suggested? In the past year, calls to decrease or reallocate police funding have entered the mainstream. The decision to invest in Digidog could be considered unethical because its benefits to the public can’t justify its significant cost. Digidogs themselves cost around $74,000 each. Considering that they are only intended for use in extreme and dangerous situations, their usage is rare, and they do not appear to improve the life of the average individual. However, by serving as a weaponless first responder, Digidogs could save both the lives of officers or those suspected of engaging in criminal activity. Human error and reactivity can be removed from the equation by having robots surveil a situation in place of an armed officer.

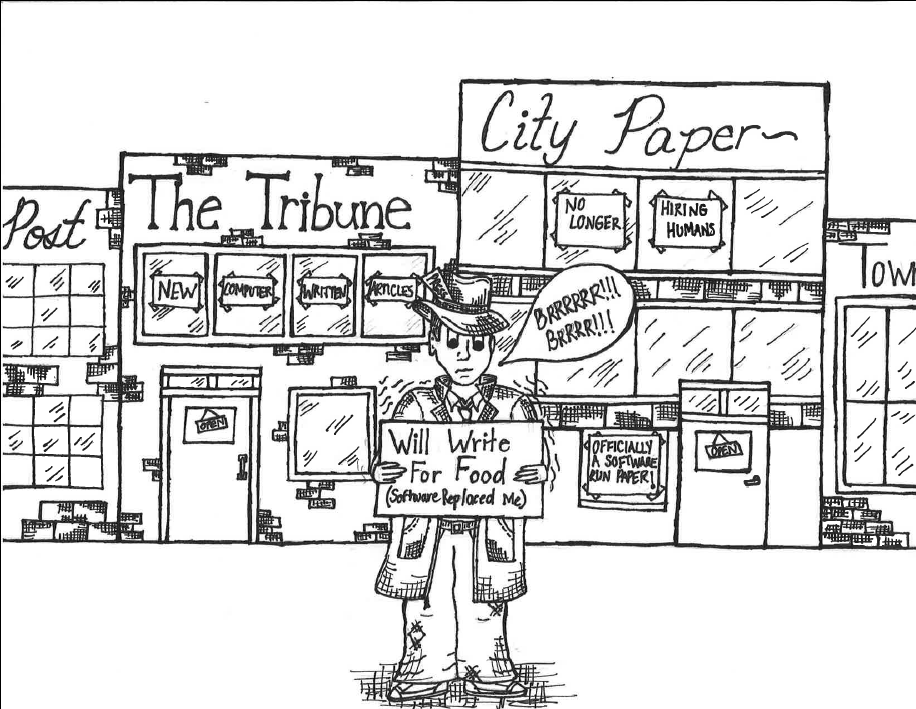

Whether or not the Digidog represents an ethical use of public funds may turn on the legitimacy of investing in crime response rather than crime prevention. As previously noted, “Spot” is primarily used to respond to existing crime. Because of this, critics have suggested that these funds would be better aimed at programs that seek to minimize the occurrence of crime in the first place. Congresswoman Ocasio-Cortez’s tweet, for example, makes reference to those who suggested resources should go to school counseling instead. In fact, some criminology experts argue that investing in local communities and schools can drastically decrease the incidence of crime. Defenders of Digidog are quick to point out that the two goals are not mutually exclusive; it is possible to invest in both crime response and crime prevention, and we need not pit these two policy aims against one another. It is unclear in this situation, however, whether similar funds were directed at preventing crime as were spent in purchasing Digidogs.

This investment in Digidog could also be seen as unethical not just in terms of its lack of efficiency in addressing crime, but also in terms of the lack of similar treatment in other areas of social concern. In a reply to her original tweet, Ocasio-Cortez retorted “when was the last time you saw next-generation, world class technology for education, healthcare, housing, etc. consistently prioritized for underserved communities like this?” In a time when so many have called to defund the police following centuries of police violence against Black people, it seems an affront to invest money in technologies designed to aid arrest rather than address systemic injustice. Highlighting this disparity in funding shows that urgent social needs are being unjustly prioritized last. Again, defenders of Digidog might respond that this comparison is a false one, and that technology can be employed for both policing and social needs.

Together, these concerns mean that Digidog’s usage will continue to be met by skepticism, if not hostility, by many. As police and surveillance technology develop, it remains especially important that we measure the value these new tools offer against their costs to both our safety and our privacy.