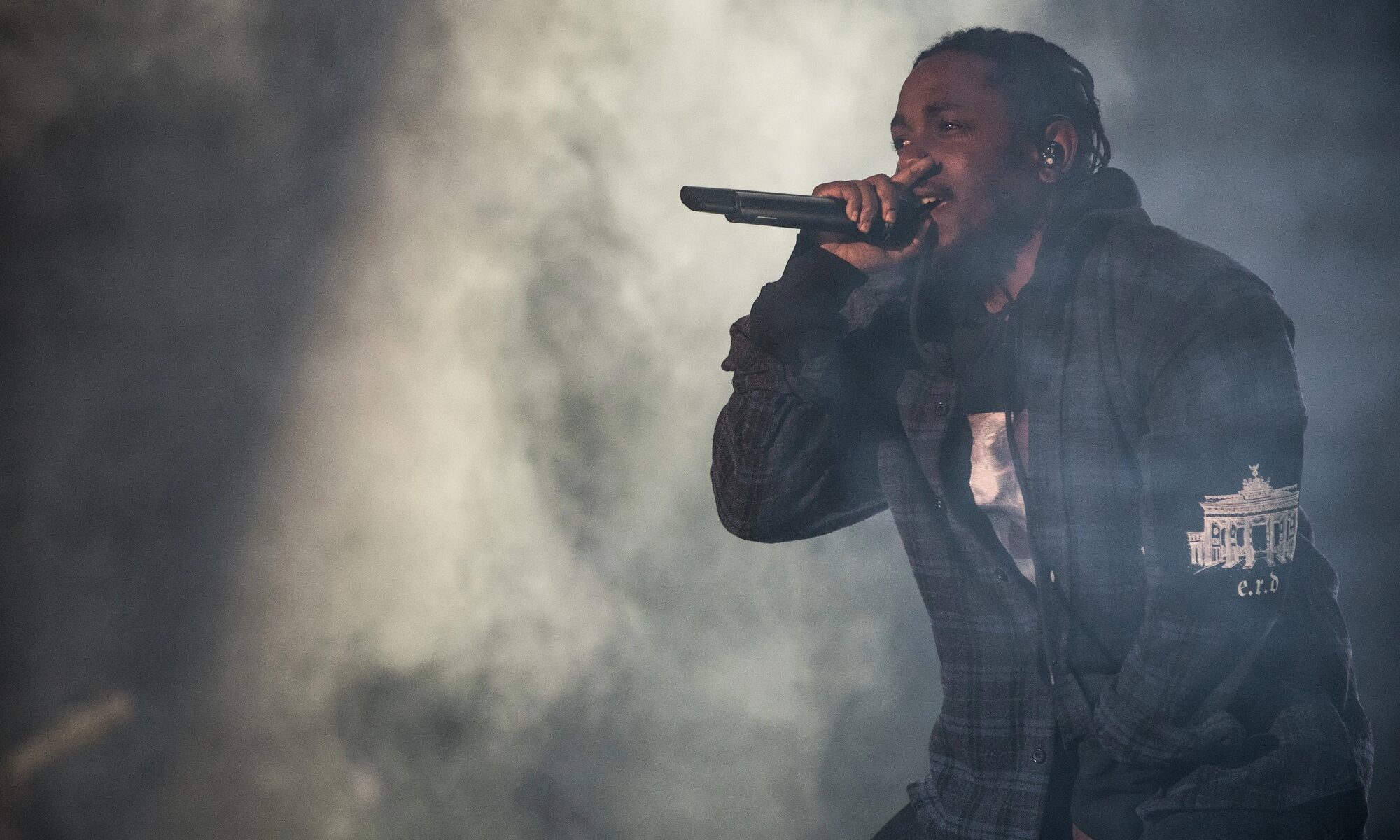

What many have called “the Rap Battle of the Century,” between rappers Drake and Kendrick Lamar, has led us into uncharted waters. Public opinion has Lamar winning handily, and he appeared to take a victory lap that included a successful album release, five Grammys, a halftime Super Bowl performance, and a worldwide tour alongside R&B singer SZA. However, following his loss, Drake sued for defamation over “Not Like Us.” Specifically, the Canadian rapper sued not Kendrick Lamar, but the record label UMG, which represents both rappers, for promoting the defamatory message contained in “Not Like Us” – i.e., the remarks regarding Drake’s not-so-much implied pedophilic tendencies. In other words: Drake and his team assume “Not Like Us” to be defamatory, and are arguing that UMG knowingly spread the song in spite of its defamatory content.

Much ink has been spilled over the lawsuit (including Lamar’s own satire of the potential trial resulting from it), its impact on Drake’s public image as a rapper, and its significance for rap music as a genre – with the worry that, were the suit to succeed, record labels would demand much more control over rappers’ songs to avoid similar fallout. However, the ink I wish to spill today is aimed at the premise of the lawsuit: i.e., whether a rap song, even a scathing one like “Not Like Us,” can be considered defamatory. If we consider rap lyrics to be part of an art form, can they be taken to be assertions of the truth? Should we take not just rap lyrics, but pieces of art in general, to be as good as statements of fact – such that those uttering them can be held liable?

This question of artistic culpability is far from new. The 1985 Senate hearings of Frank Zappa, John Denver, and Twisted Sister’s Dee Snider to discuss the (supposed) moral objectionability of rock lyrics is probably the most notorious of such cases. Rap lyrics have very often been used as evidence against the very artists that deliver them since the late 80s, with the most recent prominent example being the RICO charges against Jeffrey Lamar “Young Thug” Williams. This (mis)use of song lyrics is partly motivated by the frequent use of the first-person perspective in rap songs that deal with violence or drug use and sale. First-person storytelling give the impression of authenticity. This explains why rap lyrics have been used frequently in trials, a practice often deemed problematic for a number of reasons, including the constraint of First Amendment rights and the risk of strengthening various forms of prejudice.

There is, however, a different kind of problem regarding the use of rap lyrics as assertions of truth – something that regards all forms of artistic expressions. This problem is best highlighted in René Maigritte’s painting, known as The Treachery of Images, representing a realistic-looking pipe accompanied by the caption Ceci n’est pas une pipe (“This is not a pipe”). When looking at the painting, you may see a pipe, but it is not a pipe. It is merely a representation of a pipe. Even in art pieces committed to being as realistic as possible, the piece of art is intrinsically something other than what it means to represent. Likewise, song lyrics, especially those of diss tracks, should not be taken as genuine representations of facts – and are definitely not comparable to admissions of guilt.

Still, lyrical exchanges have led to severe consequences: most famously, the rivalry between East Coast and West Coast rappers – specifically the Bad Boy Records and Death Row Records labels – involved a variety of provocations and threats, both in and out of songs, and may very well have led to the deaths of rap icons Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G. Even more poignantly, in his feud with Gucci Mane, rapper Young Jeezy released a track where he placed a $10 million bounty on Mane’s head, potentially leading to an attempt on Mane’s life and Mane killing a man in self-defense. In such cases, the fact that the song stands ontologically separate, as a piece of art, from the reality it represents may not necessarily excuse it. This would apply even for other kinds of art pieces: just think of German comedian Jan Böhmermann, whose satirical (albeit quite offensive) poem dedicated to Turkish Prime Minister Recep Erdoğan almost caused a diplomatic incident.

So, there is a sense in which art pieces contain some kind of truth value. However, that truthfulness is not so much a statement of fact as a disclosure about the artist’s state of mind and view of the world. These remarks are closer to speech acts such as wishes, expressions of feelings, or made-up stories. At the same time, we recognize those kinds of utterances because they are an integral part of our sociality: we can recognize the differences between storytelling, wishing, ordering, praying, and making assertions of fact because we can recognize each of them as specific practices with their own logic, expectations, and rules. Making art is, itself, an instance of such practices. They have their own histories, and artists are aware and participants of such practices and their norms, values and expectations. Rap music is no different in that regard, with rap feuds, which deliberately entail the expression of negative and outright defamatory statements between rival rappers, as a part of the practice of rap as an art form.

If one accepts that art pieces, including songs, are a different kind of utterance than assertions of truth, then they should not be treated as evidence in court. Because of rap music’s nature as an art form, they should not be utilized as a purported admission of guilt. This would be even more the case for Drake’s lawsuit of UMG, as the defamatory remarks in “Not Like Us” did not come out of the blue, but were part of an exchange of hostile and defamatory remarks between him and Kendrick Lamar. These statement were part of a rap feud, a practice that characterizes the art form that existed for more than 50 years, and a history which Drake’s lawyers have tried to underplay as much as possible. Hopefully, the competitive and hyperbolic character of rap music will be recognized as essential to the art form, and Drake’s case will be dismissed.