Consider these starkly different positions on gun control: a month ago, just hours after a gunman killed 50 people worshiping at Friday prayers in two Mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, the Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, promised to tighten the country’s gun laws. And, several days ago Donald Trump told the National Rifle Association in a speech that he intends to pull out of the United Nations arms treaty citing as a reason the protection of second amendment rights. Trump said, “Under my administration, we will never surrender American sovereignty to anyone. We will never allow foreign bureaucrats to trample on your second amendment freedom.”

In the United States it is difficult to tighten gun ownership rules, or limit the types of guns (like military assault rifles, automatic and semi-automatic weapons) because ownership of guns for self-protection has been found to be protected by the second amendment of the Constitution, which states that citizens have a right to ‘keep and bear arms.’ But no such constitutional right exists in New Zealand, where Ardern swiftly followed through on her promise; nor in Australia whose gun laws, also passed in response to a massacre, New Zealand’s were modelled on.

The man charged over the Christchurch massacre was in possession of two semi-automatic rifles as well as three other firearms, all held legally on his entry-level ‘category A’ firearms licence; the semi-automatic rifles had allegedly been modified by adding a high-capacity magazine. Less than a month later a sweeping gun law reform bill was brought before the New Zealand parliament. The bill outlaws most automatic and semi-automatic weapons, and components that modify existing weapons. During the bill’s final reading, Ardern said: “I could not fathom how weapons that could cause such destruction and large-scale death could be obtained legally in this country.”

New Zealand government Members of Parliament, in a rare show of bipartisanship, overwhelmingly backed the changes, (there was just one dissenting vote in the parliament), which were passed by a vote of 119 to 1 in the House of Representatives after an accelerated process of debate and public submission. It is now illegal to own a military style rifle in New Zealand (with the exception of heirloom weapons or those for professional pest control). Possession of such a weapon will from now on carry a penalty of up to five years in prison. The bill includes a buyback scheme for anyone who already owns such a weapon, for them to surrender it and receive compensation based on the weapon’s age and condition.

New Zealand’s gun law reform was based on similar measures taken by the Australian government in 1996, following the Port Arthur Massacre in which an individual used a semi-automatic rifle to murder locals and tourists in the small historic town, ultimately killing 35 people, including many children. Twelve days after the Port Arthur massacre, the Australian prime minister, John Howard, announced a sweeping package of gun reforms. In the wake of Port Arthur, the Australian government banned automatic and semiautomatic firearms, adopted new licensing requirements, established a national firearms registry, and instituted a 28-day waiting period for gun purchases. It also bought and destroyed more than 600,000 civilian-owned firearms, in a scheme that cost half a billion dollars and was funded by raising taxes.

In both countries gun law reform had been frustrated by conservative elements prior to the massacres. In New Zealand, as in Australia, there was some pushback from conservative politics, and from a gun-lobby, but in general there was widespread community support for the banning of military style weapons, and automatic and semi-automatic rifles, as both countries grappled with extreme tragedy.

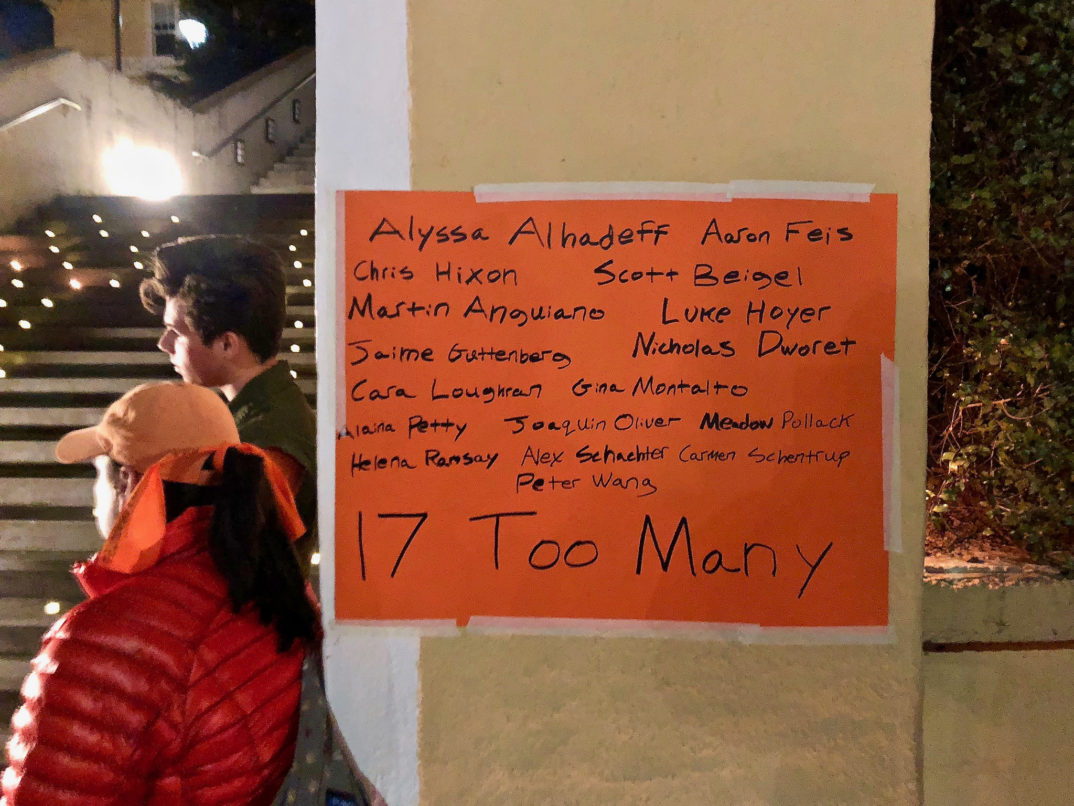

In the United States, a similar response to major firearms massacres such as Sandy Hook in 2012 and, more recently the Parkland Florida school shooting in 2018 is almost inconceivable. Any attempt to instigate reform on the back of unspeakable tragedies such as these appears doomed; indeed Barak Obama’s pledge to push through some modest reforms following Sandy Hook encountered fierce resistance from the NRA and other organisations who, in vehemently defending the constitutional right of the Second Amendment, constitute the gun-lobby.

In Australia in 1996, and in New Zealand in 2019, the governments acted on the tragedy to amend laws so as to keep people safe and to ensure such massacres do not continue to occur. There have been no mass shootings in Australia in the over 20 years since Port Arthur; in the 20 years before it there were 13. In both cases, the gun lobby was barely given time to react, and reform was swift so that it took place in the wake of the tragedy. Even though the US has a constitutional right protecting gun ownership, the gun lobby fears the capacity of governments to move to curtail gun ownership in the wake of severe massacres and large-scale tragedies, such as Sandy Hook or Parkland, and members of the NRA have expressed concerns that such mobilisation by gun control advocates in Australia, and now New Zealand, may give hope and impetus to those campaigning for gun law reform in the United States.

A main gun-lobby tactic is to criticise gun-control advocates for capitalizing on tragedy to target gun laws. Following a mass shooting it is usual for the gun lobby, and a large number of politicians as well, to offer “thoughts and prayers” and then to vehemently oppose any suggestion that gun laws need reform. One typical response from conservative second amendment defenders is that it is bad (it seems they are suggesting it is ethically bad) to use a tragedy to further a political agenda or ideology.

This tactic was spelled out clearly recently by Catherine Mortensen, an NRA media liaison officer, though she was unaware at the time of speaking, that she was being recorded. Recently several Australian politicians and political staffers were caught and secretly filmed visiting the United States and meeting with NRA and gun lobby officials and supporters, with a view to soliciting political donations. Said donations were slated to help these Australian right-wing conservative players electorally manoeuvre into a position from which to water down Australia’s gun laws. In meetings at the NRA’s Virginia headquarters, NRA officials provided Australian One Nation’s James Ashby and Steve Dickson with tips from the NRA playbook on how to galvanise public support to change Australia’s gun laws and coached the pair on how to respond to a mass shooting.

Catherine Mortensen’s advice, following a mass shooting, is: “Say nothing.” If media queries persist, go on the “offence, offence, offence.” She counsels gun lobby groups to smear gun-control groups. “Shame them” with statements such as: “How dare you stand on the graves of those children to put forward your political agenda?”

Of course, Mortensen’s point about not using tragedy to further a political agenda is, in this scenario, a totally disingenuous piece of sophistry. One of the principle points about such tragedies (Christchurch, Sandy Hook, Port Arthur) which determines how we should respond is the procurement and possession of weapons – in these cases the availability and use of military style weapons by a single person to massacre strangers. Whichever way it is talked about, how a government and community responds will always suggest some political end. Events like these rightly impede our political lives, and it is surely the role of politicians to act in the best interests of the community. Mortensen’s statement is also obviously hypocritical, considering the political clout of the NRA and the gun lobby.

It is surely time for the USA to look again at the ethics of its constitutional right to bear arms. A constitutional right is not a human right, and many now agree that the second amendment is a relic from the Eighteenth Century, when newly independent Americans may have needed “well organised militias” to protect themselves.

But as an ethical concept, the notion of a right needs to have some meaning. Although a right is an abstract, deontological concept, and is in an important sense a ‘good in itself’ it has also to be grounded in our experience of the world, and to emerge from what we know to be the case from our experience. We know that human rights pertaining to access to food and shelter and freedom from tyranny are fundamental because those things are necessary for us to flourish. But we can see from the number of massacres in America, not to mention other gun-death and injury statistics that high levels of gun ownership and availability do not contribute to a flourishing society.

The right to bear arms cannot be considered to be a right that is ‘good in itself,’ or is worthy to be protected against every tragedy and every statistic that measures the harms it causes American society. In fact, in this case, the existence of a right is a primary factor standing in the way of ethical progress.