Editor’s note: This article is the second of a brief series on Gillette’s “We Believe: The Best Men Can Be” ad that aired on January 13, 2019.

The recent Gillette short film “We Believe: The Best Men Can Be” has received vocal backlash from some viewers.

Gillette’s commercial film touched on critiques of “toxic masculinity” (also known as “hegemonic masculinity”). But the short film is also firmly rooted in empathy and concern for those who identify as male and takes up male victimization. The recurrent protagonist is a boy running from a group of relentless bullies. Terry Crews is also featured, a beloved advocate for positive masculinity who has spoken out about his experiences as a victim of sexual harassment and as the child of domestic abuse. The film also references the #MeToo movement in media montages and a mock sitcom where a white man harasses a cleaning woman of colour. It exhibits ”benign” examples of misogyny, including a moment where the camera focuses in on the expression of a woman at a corporate-looking table as her male colleague silences her and speaks over her, “Actually, what I think she’s trying to say…”

At the thirty-five second mark, the camera pans across a line of men towering over barbecues, arms pugnaciously crossed, muttering in unison ”Boys will be boys will be boys will be boys” ad infinitum. The film highlights how this classic, reductive tautology serves as a straitjacket for the supposed beneficiaries of “traditional masculinity” as much as a fortress against those who are excluded from it.

It is revealing that much of the outcry against the commercial revolves around this same circular cry, “Boys will be boys!” The backlash has a confusing logic, however. Contrary to what critics say, Gillette offers positive examples of masculinity. Its very title suggests masculinity can be more than benign – it can be superlative. The film showcases a group of young men resolving a conflict among themselves, a father nurturing his tiny daughter’s self-confidence, male figures intercepting bullying among children and checking a catcaller in his tracks, and ends with lingering shots on the thoughtful, trusting, hope-filled faces of young boys.

To what, then, do its critics object? Certainly, the commercial scrutinizes a still-prevalent version of performed “masculinity.” But gender scrutiny is deeply embedded within culture and within advertising as a particularly influential capitalist cultural medium. Femininities are regularly examined. Women are routinely exposed to media and discourses that tell them how to be women. These injunctions include impossible expectations of thinness and narrowly Western beauty ideals, enforcing traditionally female occupations overcoming workforce barriers without seeming too female, balancing being caregivers, breadwinners, and managing an enviable “lifestyle” for themselves and their loved ones while exhibiting positive emotion and self-control in all things, being confident and assertive without coming across as aggressive, being maternal without giving up one’s career and vice-versa, et cetera (for more details on women and perfectionism, click here, here, and here). These themes are so ubiquitous as to be immediately recognizable in satire. (One such satire is “Man who has it all,” a social media experiment that switches the male for the female gender in providing “helpful lifestyle tips” and highlights the pressures which advertisers and culture-at-large place on women to be perfect in every way to achieve minimal respectability.)

Masculinities and femininities are undoubtedly subject to interrogation and contestation. But it seems peculiar for a short film to inspire such controversy for encouraging men to be role models for the next generation by rejecting abuse, violence, and unreasoning defensiveness. Some may question whether companies are best positioned to further our social conscience, while others welcome corporations taking on responsibility even if driven by a profit motive to be on the side of social evolution.

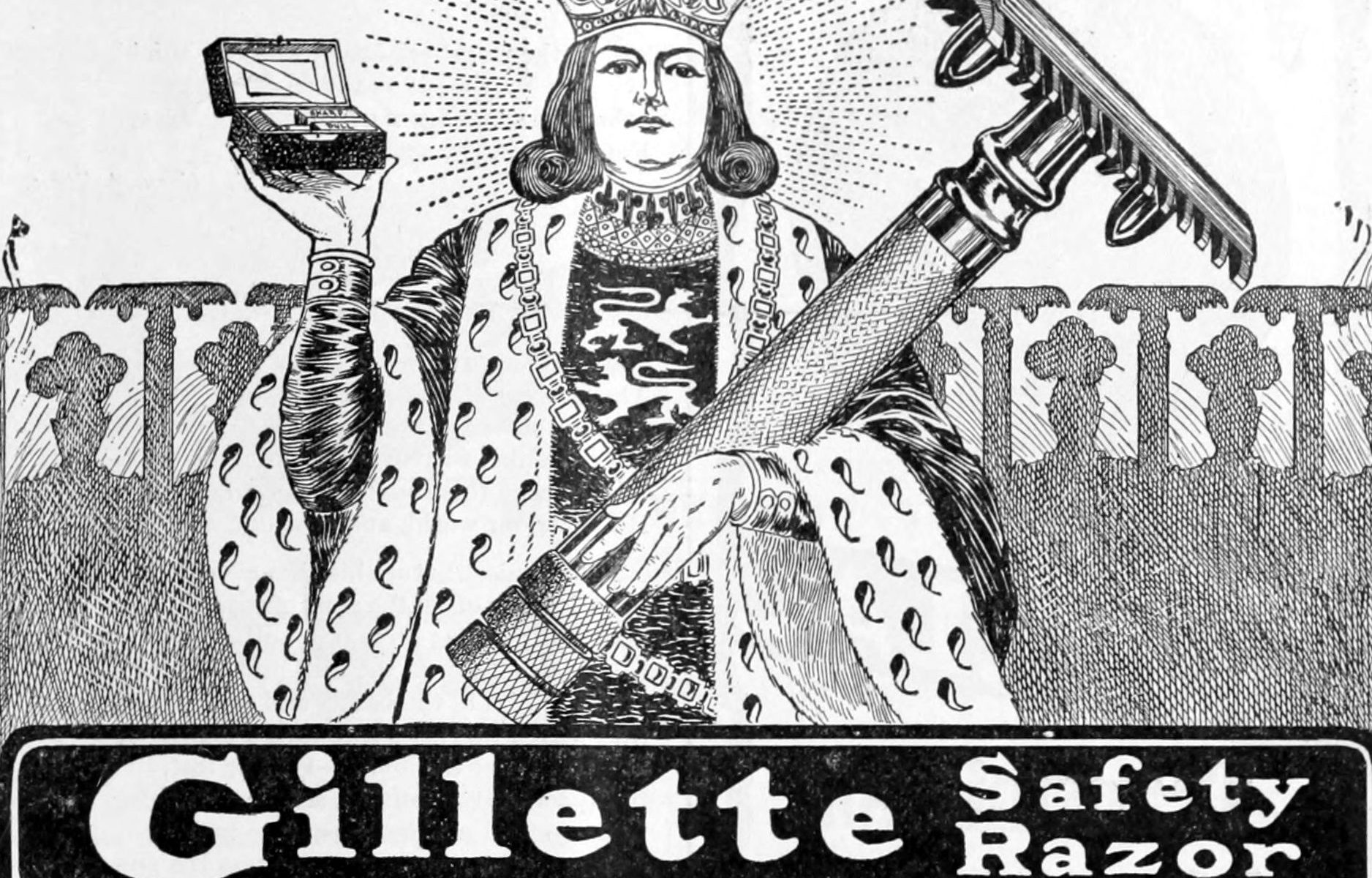

Gillette’s ad ultimately advocates an extremely parsimonious set of norms — a minimum bar of human decency by any gender standard. Some could even argue that it does so by endorsing some traditional conceptions of masculinity as honorable and strong or ‘’virtuous’’ (in its etymological connotations of ‘’manliness’’). For some, the ad endorsed truly “manly” behaviour, reminiscent of the concept of a “gentleman,” which, along with its conceptual counterpart of “ladies,” is also grounded in highly specific gendered, racial and classed identity and performance.

The American Psychological Association recently came out with its first guide to practice with men and boys. This represents a moment of introspection in psychological discipline. The APA has had a guidebook for treating women and girls since 2007. But the need to examine masculinities as an object of observation to the sciences and not merely as the default subject is overdue by much more than a decade. As in other disciplines, the typical psychological subject was presumed to be a white male, a standing point that served as a proxy for the whole human race. While psychology is not unique in assuming a European-descended male as its implicit subject this moment is revealing how limiting a privileged standing point can be, even to those who accrued social benefits from being silently and exclusively represented as the default in the network of knowledge and power domains.

The default male figure as the unquestioned subject of knowledge traditionally understood can now also be the object of social gaze and reflection. Perhaps it is inevitable for this to be the source of some anxiety. In this case, the APA’s guidelines are well-timed to this social moment.