Like many educators, I have encountered difficulties with Generative AI (GenAI); multiple students in my introductory courses have submitted work from ChatGPT as their own. Most of these students came to (or at least claimed to) recognize why this is a form of academic dishonesty. Some, however, failed to see the problem.

This issue does not end with undergraduates, though. Friends in other disciplines have reported to me that their colleagues use GenAI to perform tasks like writing code they intend to use in their own research and data analysis or create materials like cover letters. Two lawyers recently submitted filings written by ChatGPT in court (though the judge caught on as the AI “hallucinated” case law). Now, some academics even credit ChatGPT as a co-author on published works.

Academic institutions typically define plagiarism as something like the following: claiming the work, writing, ideas or concepts of others as one’s own without crediting the original author. So, some might argue that ChatGPT, Dall-E, Midjourney, etc. are not someone. They are programs, not people. Thus, one is not taking the work of another as there is no other person. (Although it is worth noting that the academics who credited ChatGPT avoid this issue. Nonetheless, their behavior is still problematic, as I will explain later.)

There are at least three problems with this defense, however. The first is that it seems deliberately obtuse regarding the definition of plagiarism. The dishonesty comes from claiming work that you did not perform as your own. Even tho GenAI is not a person, its work is not your work – so using it still involves acting deceptively, as Richard Gibson writes.

Second, as Daniel Burkett argues, it is unclear that there is any justice-based consideration which supports not giving AI credit for their work. So, the “no person, no problem” idea seems to miss the mark. There’s a case to be made that GenAIs do, indeed, deserve recognition despite not being human.

The third problem, however, dovetails with this point. I am not certain that credit for the output of GenAIs stops with the AI and the team that programmed it. Specifically, I want to sketch out the beginnings of an argument that many individuals have proper grounds to make a claim for at least partial ownership of the output of GenAI – namely, those who created the content which was used to “teach” the GenAI. While I cannot fully defend this claim here, we can still consider the basic points in its support.

To make the justification for my claim clear, we must first discuss how GenAI works. It is worth noting, though, that I am not a computer scientist. So, my explanation here may misrepresent some of the finer details.

GenAIs are programs that are capable of, well, generating content. They can perform tasks that involve creating text, images, audio, and video. GenAI learns to generate content by being fed large amounts of information, known as a data set. Typically, GenAIs are trained first via a labeled data set to learn categories, and then receive unlabeled data which they characterize based on the labeled data. This is known as semi-supervised learning. The ability to characterize unlabeled data is how GenAIs are able to create new content based on user requests. Large language models (LLMs) (i.e., text GenAI like ChatGPT) in particular learn from vast quantities of information. According to Open AI, their GPT models are trained, in part, using text scraped from the internet. When creating output, GenAIs predict what is likely to occur next given the statistical model generated by data they were previously fed.

This is most easily understood with generative language models like ChatGPT. When you provide a prompt to ChatGPT, it begins crafting its response by categorizing your request. It analyzes the patterns of text found within the subset of its dataset that fit into the categories you requested. It then outputs a body of text where each word was statistically most likely to occur, given the previous word and the patterns observed in its data set. This process is not just limited to LLMs – GenAIs that produce audio learn patterns from data sets of sound and predict which sound is likely to come next, those that produce images learn from sets of images and predict which pixel is likely to come next, etc.

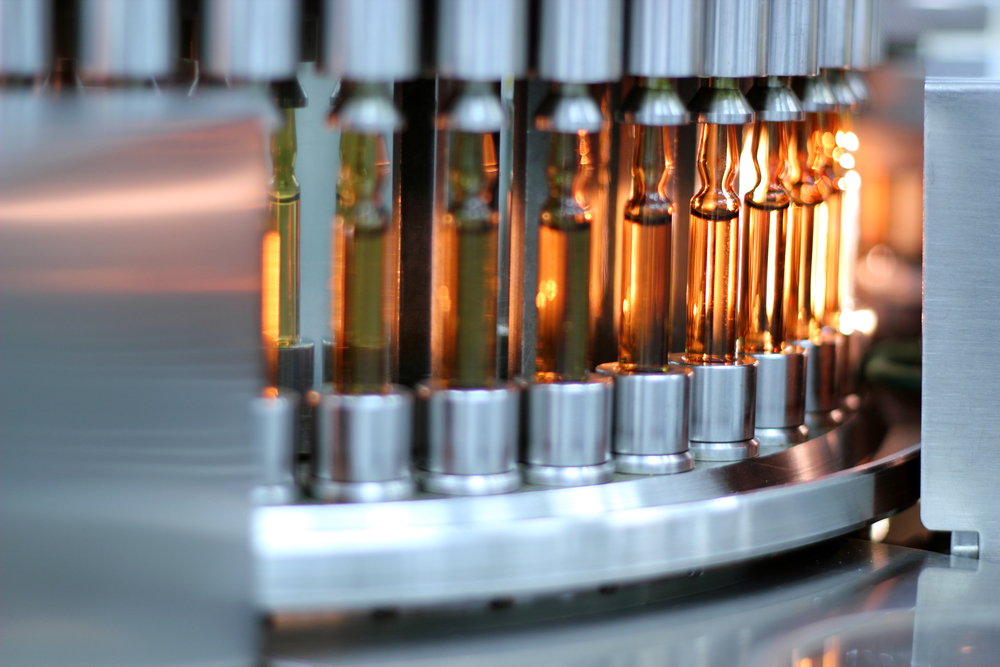

GenAI’s reliance on data sets is important to emphasize. These sets are incredibly large. GPT3, the model that underpins ChatGPT, was trained on 40 terabytes of text. For reference, 40 TB is about 20 trillion words. These texts include Wikipedia, online bodies of books, as well as internet content. Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and DreamUp – all image GenAIs – were trained on LAION, which was created by gathering images from the internet. The essential takeaway here is that GenAI are trained on the work of countless creators, be they the authors of Wikipedia articles, digital artists, or composers. Their work was pulled from the internet and put into these datasets without consent or compensation.

On any plausible theory of property, the act of creating an object or work gives one ownership of it. In perhaps the most famous account of the acquisition of property, John Locke argues that one acquires a previously unowned thing by laboring on it. We own ourselves, Locke argues, and our labor is a product of our bodies. So, when we work on something, we mix part of ourselves with it, granting us ownership over it. When datasets compile content by, say, scraping the internet, they take works created by individuals – works owned by their creators – compile them into data sets and use those data sets to teach GenAI how to produce content. Thus, it seems that works which the programmers or owners of GenAI do not own are essential ingredients in GenAI’s output.

Given this, who can we judge as the rightful owners of what GenAI produces? The first and obvious answer is those who program the AI, or the companies that reached contractual agreements with programmers to produce them. The second and more hidden party is those whose work was compiled into the data sets, labeled or unlabeled, which were used to teach the GenAI. Without either component, programs like ChatGPT could not produce the content we see at the quality and pace which they do. To continue to use Locke’s language, the labor of both parties is mixed in to form the end result. Thus, both the creators of the program and the creators of the data seem to have at least a partial ownership claim over the product.

Of course, one might object that the creators of the content that form the datasets fed to a GenAI, gave tacit consent. This is because they placed their work on the internet. Any information put onto the internet is made public and is free for anyone to use as they see fit, provided they do not steal it. But this response seems short-sighted. GenAI is a relatively new phenomenon, at least in terms of public awareness. The creators of the content used to teach GenAI surely were not aware of this potential when they uploaded their content online. Thus, it is unclear how they could consent, even tacitly, to their work being used to teach GenAI.

Further, one could argue that my account has an absurd implication for learning. Specifically, one might argue that, on my view, whenever material is used for teaching, those who produced the original material would have an ownership claim on the content created by those who learn from it. Suppose, for instance, I wrote an essay which I assigned to my students advising them on how to write philosophy. This essay is something I own. However, it shapes my students’ understanding in a way that affects their future work. But surely this does not mean I have a partial ownership claim to any essays which they write. One might argue my account implies this, and so should be rejected.

This point fails to appreciate a significant difference between human and GenAI learning. Recall that GenAI produces new content through statistical models – it determines which words, notes, pixels, etc. are most likely to follow given the previous contents. In this way, its output is wholly determined by the input it receives. As a result, GenAI, at least currently, seems to lack the kind of spontaneity and creativity that human learners and creators have (a matter D’Arcy Blaxwell demonstrates the troubling implications of here). Thus, it does not seem that the contents human learners consume generate ownership claims on their output in the same way as GenAI outputs.

I began this account by reflecting on GenAI’s relationship to plagiarism and honesty. With the analysis of who has a claim to ownership of the products created by GenAI in hand, we can more clearly see what the problem with using these programs in one’s work is. Even those who attempt to give credit to the program, like the academics who listed ChatGPT as a co-author, are missing something fundamentally important. The creators of the work that make up the datasets AI learned on ought to be credited; their labor was essential in what the GenAI produced. Thus, they ought to be seen as part owner of that output. In this way, leaning on GenAI in one’s own work is an order of magnitude worse than standard forms of plagiarism. Rather than taking the credit for the work of a small number of individuals, claiming the output of GenAI as one’s own fails to properly credit hundreds, if not thousands, of creators for their work, thoughts, and efforts.

Further still, this analysis enables us to see the moral push behind the claims made by the members of SAG-AFTRA and the WGA who are striking, in part, out of concern for AI learning from their likeness and work to mass produce content for studios. Or consider The New York Times ongoing conflict with OpenAI. Any AI which would be trained to write scripts, generate an acting performance, or relay the news would undoubtedly be trained on someone else’s work. Without an agreement in place, practices like these may be tantamount to theft.