Last year, Hurricane Ida caused around $30 billion in damages. This cost was largely borne by insurers, forcing some companies to declare insolvency. The United States is now on the brink of another active hurricane season, and – as a result – insurers in some of the riskiest parts of the country are cancelling home insurance policies. Around 80,000 homes in Louisiana have already lost their coverage, with an additional 80,000 Floridian policy holders set to be affected by the end of this week.

This is nothing new. The worsening climate crisis has seen a marked increase in the number of uninsurable homes. For example, in Australia – a country blighted by recent wildfires and floods – around 720,000 homes are set to be completely uninsurable by the end of the century. When these homes are damaged or destroyed, their occupants are left destitute.

What, then, should we be doing to help these people? More generally, what kind of moral obligations do we have to people who lose their homes as the result of a natural disaster?

One way of approaching this issue is through the concept of “luck.” We experience luck all the time – some of it good, some of it bad. And bad luck comes in many different forms: We might have our car destroyed by an errant bolt of lightning; or we might lose our entire life savings betting on a bad hand of poker. In both cases, we’re left worse off. But the obligation on others to help us may very well differ. Consider the bolt of lightning. This is, perhaps, the purest example of a case of “brute” bad luck. Compare this with that losing hand of poker. Sure, there’s still an element of luck at play: if the random shuffle of the deck had dealt me a better hand, I might’ve won. But I knew what I was signing up for. I made a calculated gamble knowing there was a good chance I might lose all of my money. Unlike the bad luck of being struck by lightning, the losing hand of poker was bad luck I opted in to – “option” luck, if you will.

This distinction between “brute” bad luck and “option” bad luck forms an important part of how Luck Egalitarians see our obligations to help others.

Stated in its simplest form, Luck Egalitarianism says that we have a moral obligation to help those who suffer from bad brute luck, but not those who suffer from bad option luck.

So, how does Luck Egalitarianism help us with disaster-prone homeowners? Well, wildfires and floods are (like bolts of lightning) clear cases of bad brute luck. But this doesn’t necessarily mean we have an automatic obligation to help those who lose their homes to such disasters. Here’s the thing: wildfires and floods aren’t entirely unpredictable. They tend to occur in disaster-prone areas, and such areas are usually well-documented. In fact, those who choose to build their homes in a risky location will usually find themselves paying substantially less for their homes. In this way, these people make a calculated gamble – so when disaster does inevitably strike, it is instead a case of bad option luck, not brute luck.

At least, it used to be this simple. For a long while, disaster-prone areas were largely stable. But the climate crisis has seen a swift end to that. Risky areas are growing, and wildfire and flood seasons are lengthening and worsening. Someone who chose to build in a safe area several decades ago may now find their home regularly in the path of catastrophe.

But what about the fact that these people choose to stay in disaster-prone areas? Sure, there may have initially been no risk in that location, but now that there is, doesn’t their choice to stay make any disaster that befalls them a case of bad option luck?

The Luck Egalitarian would say “yes” – but only if a homeowner actually has a choice in the matter. Sadly, many don’t. Selling a home that’s at risk of imminent destruction is hard. What’s more, selling it for a price that allows the occupants to afford a new home in a safer area is even more difficult. For this reason, many disaster-prone homeowners find themselves stranded – unable to afford to move. So, if someone builds a home in an area that later becomes disaster-prone, and – as a result – cannot afford to move, the Luck Egalitarian will still see the destruction of their home as a case of bad brute luck.

But there’s one final complication – namely, the role played by insurance. According to some Luck Egalitarians, the availability of affordable insurance is sufficient to convert bad brute luck into bad option luck. Why? Consider the lightning example again. Suppose that automotive lightning strikes are frequent in my area, but that full lightning coverage for my car is available for only $1 per month. I, however, opt not to purchase this insurance and instead spend my money on something more frivolous. Suppose, then, that the inevitable happens and my car is destroyed by a random bolt of lightning. While the lightning might be an “act of God,” the loss of my car is not. Why?

Because that loss is a combination of both the lightning and my calculated gamble to not purchase insurance. I, essentially, signed up for the loss of my car.

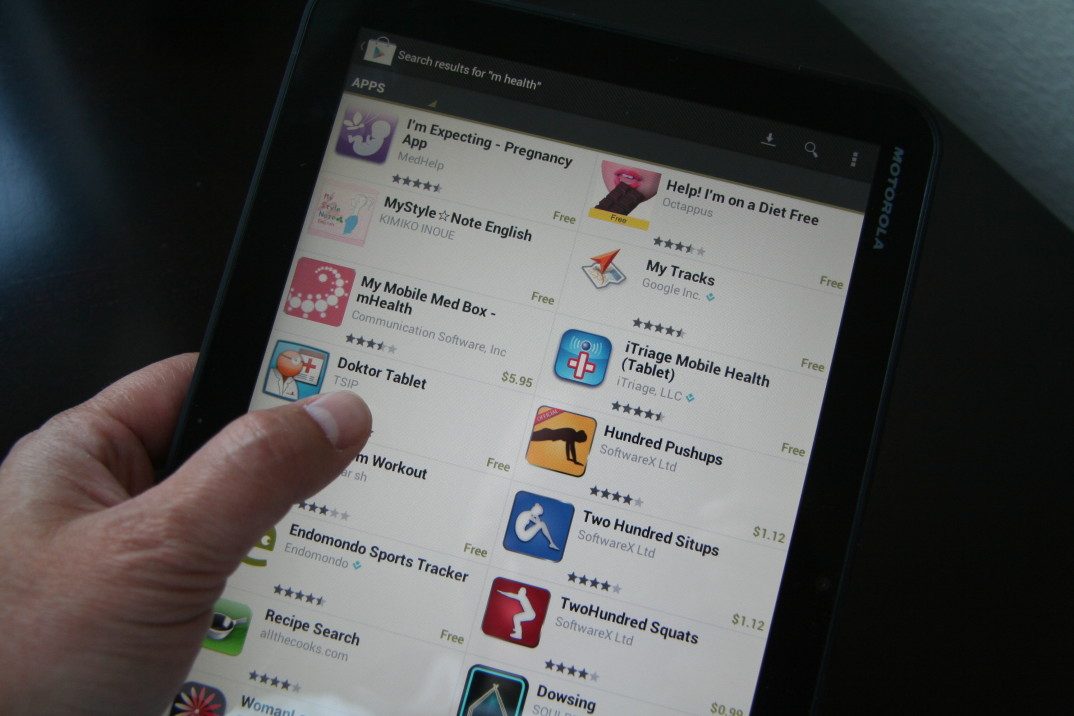

This is why insurance is so important when considering what we owe to disaster-prone homeowners. If affordable insurance is widely available – and a homeowner refuses to purchase it – any disaster that befalls them will be a case of bad option luck. This will mean that – for the Luck Egalitarian, at least – the rest of us have no specific moral obligations to help those individuals. When such insurance isn’t available, however (as it no longer is for many residents of Louisiana and Florida) the story changes. Those who (1) built their homes in previously safe areas that have now become disaster-prone; (2) subsequently cannot afford to move; and (3) inevitably find themselves the victims of natural disasters are victims of bad brute luck. And this may very well put strong moral obligations on the rest of us to come to their aid – either as individuals, or through our elected government. As the climate crisis worsens – and more and more homes become uninsurable – the need for this kind of assistance will only grow.