In the Saint Jacques district of Perpignan, France, a group of Catalan Gypsies (“les gitans”) made a stand last August for the preservation of their deteriorating historic neighborhood. The city wanted to demolish and replace hundreds of buildings for the sake of the health and safety of these residents, but the residents argued that their cultural connection to the architecture was worth more than the benefit of modern buildings. The city backed down, but there is no reason to believe that the issue is settled. As buildings in cities all over the world begin to show their age, and as municipal governments realize that these picturesque neighborhoods are among their most treasured assets, the challenge of balancing heritage and progress is becoming increasingly relevant. What should cities be doing to preserve their cultural monuments while people are living inside? Continue reading “What is the Cultural Cost of Urban Development?”

Homeless in Utah, Desperately Seeking a Backyard

This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

For more than 60 years, the sprawling Utah State Prison sat nestled at the base of the Wasatch Mountain range in Draper, Utah. The prison was home to such notorious inmates as serial killers Ted Bundy and Gary Gilmore, and serial pedophile and cult leader Warren Jeffs. Utah was the first state to reinstitute the death penalty after the Supreme Court’s moratorium ended in 1973, and the state has since executed 51 people. In 2015, the Utah legislature made the decision to relocate the prison to West Salt Lake City. In its place, Draper Mayor Troy Walker proposed to house something that, as it turns out, struck Draper citizens as far more distasteful than even the prison—a shelter for the homeless.

The proposal was part of a plan to disperse the burgeoning 1,100-resident caseload of the The Road Home, a homeless shelter located in Salt Lake City. Walker’s specific proposal was for Draper to take on the responsibility of a subsection of that population—a group of women actively looking for work, and their dependent children. Explaining his decision to throw Draper’s name into the ring for the site of the new shelter, Walker said, “It’s the right thing to do; it’s the Christian thing to do. It’s the thing that will set us apart and make us the kind of people we are.”

Dutiful to his constituency, Walker held a town hall meeting on the topic at a local middle school. Nearly 1,000 people attended. Some of them packed the halls outside of the auditorium to avoid fire code violations. Video of the meeting that ensued quickly went viral on the Internet. Attendees of the meeting were overwhelmingly opposed to the relocation of the homeless shelter in their town. At one, point, a homeless man stood up to testify to his experience with how homeless shelters benefit their charges. He was booed into silence.

Many watching the situation closely are concerned by the gentrification that they are seeing. The Salt Lake bedroom community of Draper is becoming more and more upscale. Property on the base of the mountain is prime real estate. The new site of the prison is near the Salt Lake International Airport and Rose Park, one of the least affluent communities in the area. Already home to a number of halfway houses, rehab centers, and a parole violator center, Rose Park can expect a new prison instead of the remodeled fairgrounds that they were promised. The refusal of the homeless shelter seems to be motivated by similar considerations. The “not in my backyard!” mentality seems to entail either a desire for institutions like prisons and homeless shelters to not exist at all, or for their location to be in other, poorer, backyards.

Many moral theories emphasize the value of universalizability. The idea is that, if you want to ensure that your decision is a moral one, it has to be a decision that you wouldn’t mind if someone else made under circumstances that were sufficiently similar. If we want to bar homeless shelters from our own communities, we must be comfortable with everyone else barring homeless shelters from their communities as well. Of course, we can’t do that unless we simply want homeless shelters to no longer exist. After all, every community is someone’s community.

Of course, the concerns of the citizens of Draper are not entirely baseless. Homeless shelters are not good for property values. Though we don’t want to confuse correlation with causation, it is true that property values are 12.7 percent lower in areas with homeless shelters than they are in other areas (all other things being equal). Homeowners have obligations to provide for themselves and their families. Their ability to do this may be compromised if they lose equity in their homes.

Homeowners also have a legitimate interest in their own safety, and the safety of their families. Mental illness is common among the homeless population, and so is drug and alcohol abuse. Residents of the area may have justifiable concerns that their communities will be less stable if the homeless population is introduced.

It is worth pointing out, however, that less affluent families living in lower-income communities have the same safety and stability fears as the Draper residents. If the concerns of the Draper residents are justified, and if those concerns are sufficient for the Mayor of Draper to withdraw his offer of the prison as a location for the needs of the state’s homeless, why aren’t the identical concerns of those living in less affluent communities deserving of equal consideration?

Let’s not forget the plight of the homeless population. Many moral philosophers have suggested that the best measure of the morality of a society is the way the least advantaged members of that society are treated. Booing a homeless person into silence at a town hall meeting doesn’t say anything good about the society in which that kind of thing happens.

There is a silver lining to this cloud, however. Though this particular situation suggests that there is room for some serious character development on the part of many Utah citizens, Utah has been making international news in a more positive way for a different approach to homelessness. Implementing a novel new approach called “Housing First,” Utah has reduced homelessness by 72 percent over nine years. The idea behind this approach is to do what the name suggests—provide housing to homeless people right away, without making that housing contingent on mental health or sobriety. When dealt with in this way, 88 percent of the homeless population remains in the housing a year later, at a cost to the state less than it incurred when the homeless people were on the street.

The success of the Housing First program suggests a need to change our collective mindset toward the homeless, and perhaps about access to crucial human goods and services as well. It makes sense, not just from a legal perspective, but also from a moral perspective, to attend to the basic needs of all human beings, especially those that are much less fortunate than the rest of us.

The Gentrification of Hip-Hop

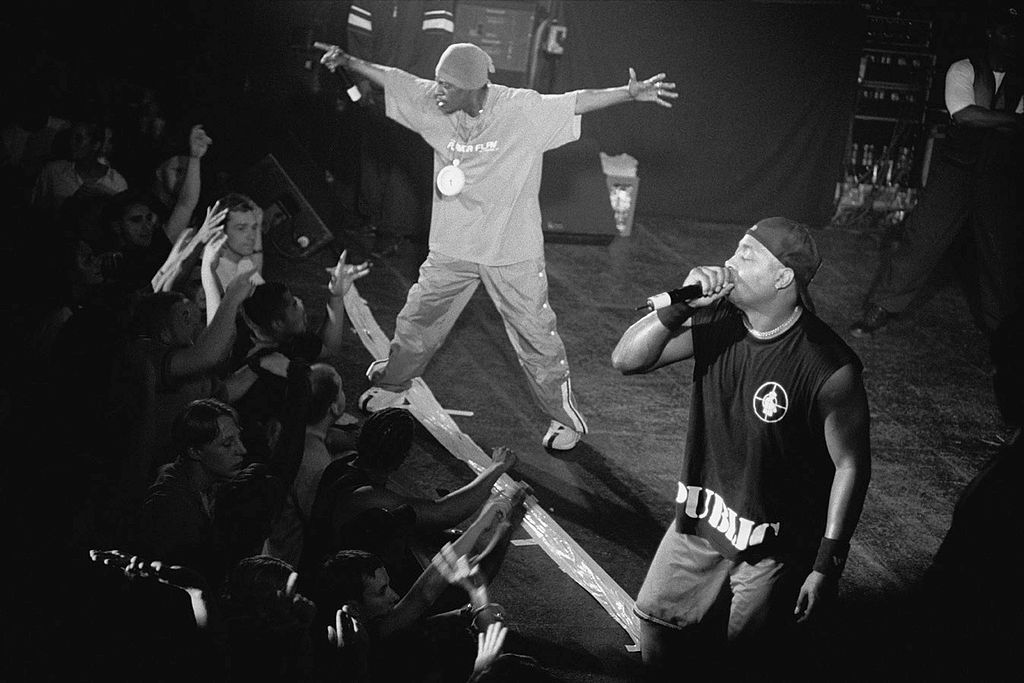

Hip-hop music began in the 1980s, and was primarily a means for African American communities to express commentary and frustration related to politics, discrimination, and common struggles often related to race relations. Crucially, music was being used to give voice to a people that has traditionally been suppressed or discounted because of the effects of systemic racism in the American political institution. One of the most significant groups to pioneer this genre was Public Enemy, whose music focused largely on sociopolitical commentary.