South Korea has a total fertility rate (TFR) of 0.75 children per woman — the lowest in the world. Even assuming the fertility rate stabilizes, for every 100 people alive today, there will only be five great-grandchildren. In three generations, the nation will have withered to near extinction.

South Korea is an extreme case, but it is hardly alone. Chile has a TFR of 1.13 (18 great-grandchildren per 100 current people — assuming birth rates do not continue to fall or that young people do not flee the collapsing country); Thailand has a TFR of 1.20 (22 great-grandchildren); Finland has a TFR of 1.30 (27 great-grandchildren). Contrary to common messaging, this is a widespread problem affecting diverse populations. In fact, the majority of countries around the world have sub-replacement birth rates.

One critical reason for concern is the sustainability of systems such as Social Security. The ratio of workers to beneficiaries has declined from 5.1:1 in 1960 to 2.8:1 today. Evermore retirees are dependent on the labor of increasingly few workers, who are being squeezed to keep the system afloat. These welfare programs cannot persist at the current numbers — and their collapse would be catastrophic. Around 1 in 10 Social Security recipients would be unable to pay their bills if checks were delayed by just one month. Beyond Social Security, many people’s retirement security is embedded in systems which presuppose economic and population growth.

Demographic collapse also imperils cultural diversity. Cultures are carried by people. And, as communities become barren of economic opportunities, individuals will face increasing pressure to abandon their homelands. Languages, traditions, and identities will increasingly fade away as the communities which sustain them disappear. This is not merely a poetic lament — UNESCO reports that a language dies every two weeks, often as a result of demographic and economic displacement.

It’s also important to note that, in most developed countries, people want more children than they are able to have. Around 90% of Americans either already have children, want children in the future, or wish they had children in the past. Among those over 45, the average ideal number of children — if they could do it again — is 2.6, far above the current TFR of 1.62. A majority of childless people over 45 wish they had at least two. Pronatalism, then, is not merely about economic or cultural survival. It’s about enabling people to live the lives they already want — lives stymied by economic precarity, social atomization, and institutional failure.

Environmental concerns are legitimate. More people means more consumption. But the relationship between population and environmental degradation is neither linear nor fixed. Today’s most urgent ecological crises — carbon emissions, habitat loss, resource depletion — stem primarily from unjust and unsustainable systems of production and consumption. Ironically, many of the countries facing demographic collapse have the lowest per-capita environmental footprints. While a shrinking, aging population may slightly reduce emissions in the short term, it also drains the labor, creativity, and vitality needed for long-term ecological stewardship. Rather than treating people as liabilities to the planet, we should recognize that future generations — if raised with care, education, and ecological values — are our best hope for building a sustainable world. To shape the future, humanity must first persist into it.

Some have characterized demographic concerns as a right-wing issue. There’s some truth to this. Figures like Elon Musk and J.D. Vance have been among the most vocal about this problem. But the ideological provenance of a problem is no reason to ignore its substance. Conservatives shouldn’t dismiss climate change because it’s associated with the left; likewise, progressives shouldn’t disregard demographic collapse just because its loudest messengers are on the right. Moreover, demographic collapse is coming regardless of who cares about it; to cede the problem to one’s ideological adversaries is to forfeit influence over its solutions.

Some argue that immigration can counteract low birth rates, but this misunderstands the nature of the problem. Immigration may delay some of the effects of demographic collapse, but it cannot resolve them. Immigrants from high fertility countries quickly see their fertility decline upon arrival. Moreover, native citizens also experience falling fertility in response to high immigration rates. Furthermore, viewing demographic decline as a mere numbers game misses the central concern: age structure. A graying population places immense burdens on younger generations, regardless of total population size. Most importantly, as noted earlier, demographic collapse is a global phenomenon. Of the top ten countries of origin for US immigrants — only one, Guatemala — has above-replacement fertility. Immigration allows rich countries to persist by drawing vitality from nations facing the same underlying problem. It’s a demographic shell game, not a solution.

If immigration isn’t viable long-term, what is? The most common answer is financial incentives — paid parental leave, subsidized childcare, and child tax credits. However, while parents would surely appreciate more money in their pockets, recent interventions seem to suggest that such subsidies do not substantively raise birthrates. Poland and Hungary spend 3.5% and 5% of their GDP on pro-natal policies respectively, yet have seen only modest gains in birth rates.

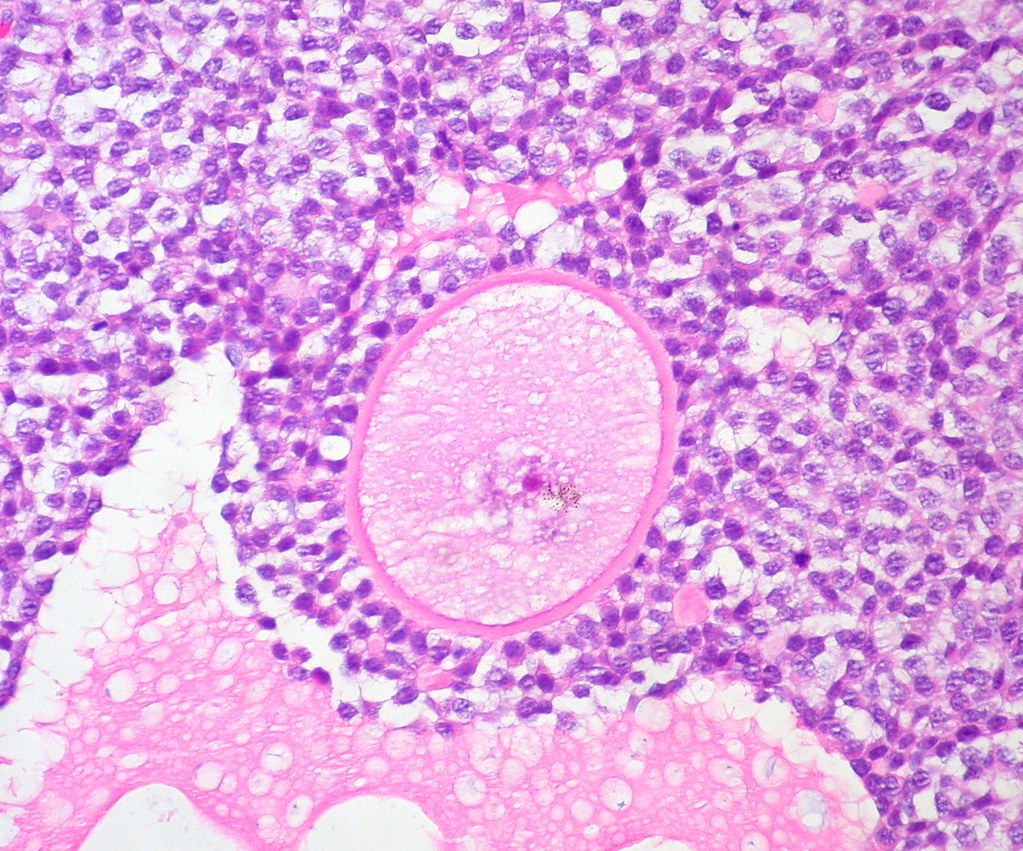

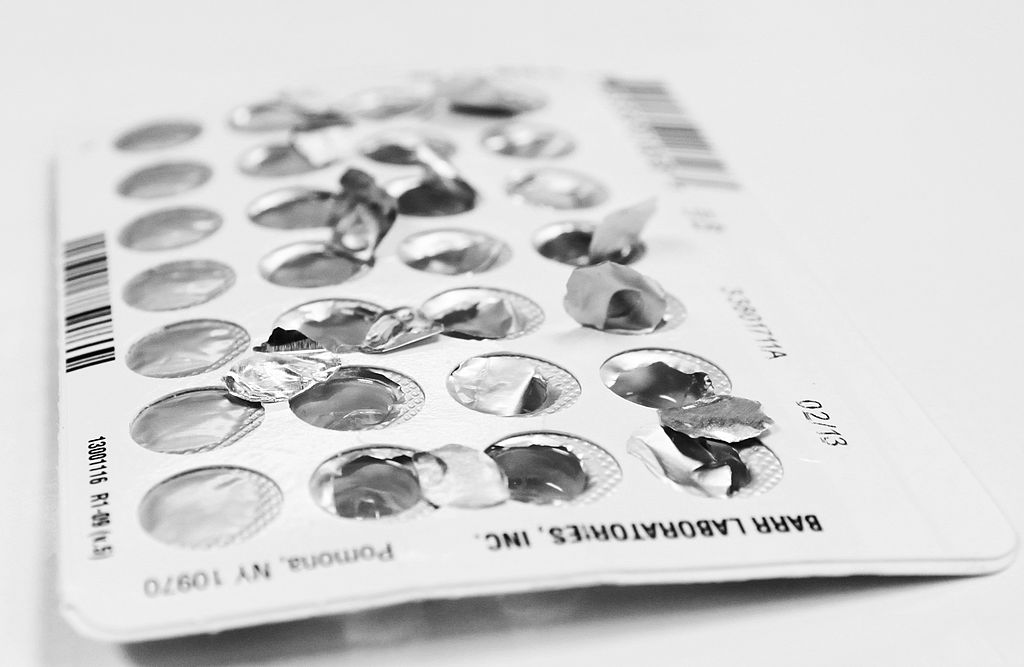

Because concerns about fertility decline are more common on the right — and because fertility was higher in poorer, more patriarchal societies — some suspect that pronatalism is a Trojan Horse for restricting women’s freedom. Setting aside principled objections to such repression, the data shows that restricting abortion and contraception is not a durable fix. Fertility may rise briefly, but the gains do not persist and in fact may invert as people adjust to their new, more repressive realities.

So, if immigration, coercion, and cash transfers don’t suffice, what might? The answer is unclear. Some researchers hold out hope for the efficacy of modified wealth transfers, such as income tax reductions, removing sales taxes on goods related to childcare, or modifying incentives around Social Security. Others advocate for expanding access to — and increasing research into — fertility treatments, allowing individuals to delay family formation without giving it up entirely. More still point out the tight link between housing and fertility, suggesting we need to loosen up zoning codes to allow for the production of more family-friendly housing.

Others, however, are pessimistic on the efficacy of policy and insist that demographic collapse is an essentially cultural problem. Researchers point to the (unsurprising) connection between marriage and fertility and the need to support those looking to get and stay married. Proposals include not shaming those who get married young or have larger families, normalizing working from home, and destigmatizing intergenerational living. Others point to examples such as Mongolia and Georgia and argue that the key to fixing this problem is raising the status of parents. More still emphasize changing norms around parenting to encourage equitable household labor, alleviate burdens from both parents, and better align with scientific realities.

The prospect of unmitigated demographic collapse — vanishing cultures, faltering economies, fractured communities — is frightening. But it also presents a rare opportunity to rethink the systems and values that structure modern life. Rather than resigning ourselves to decline, we can rise to the challenge of sustaining human flourishing.

The future belongs to those who show up.