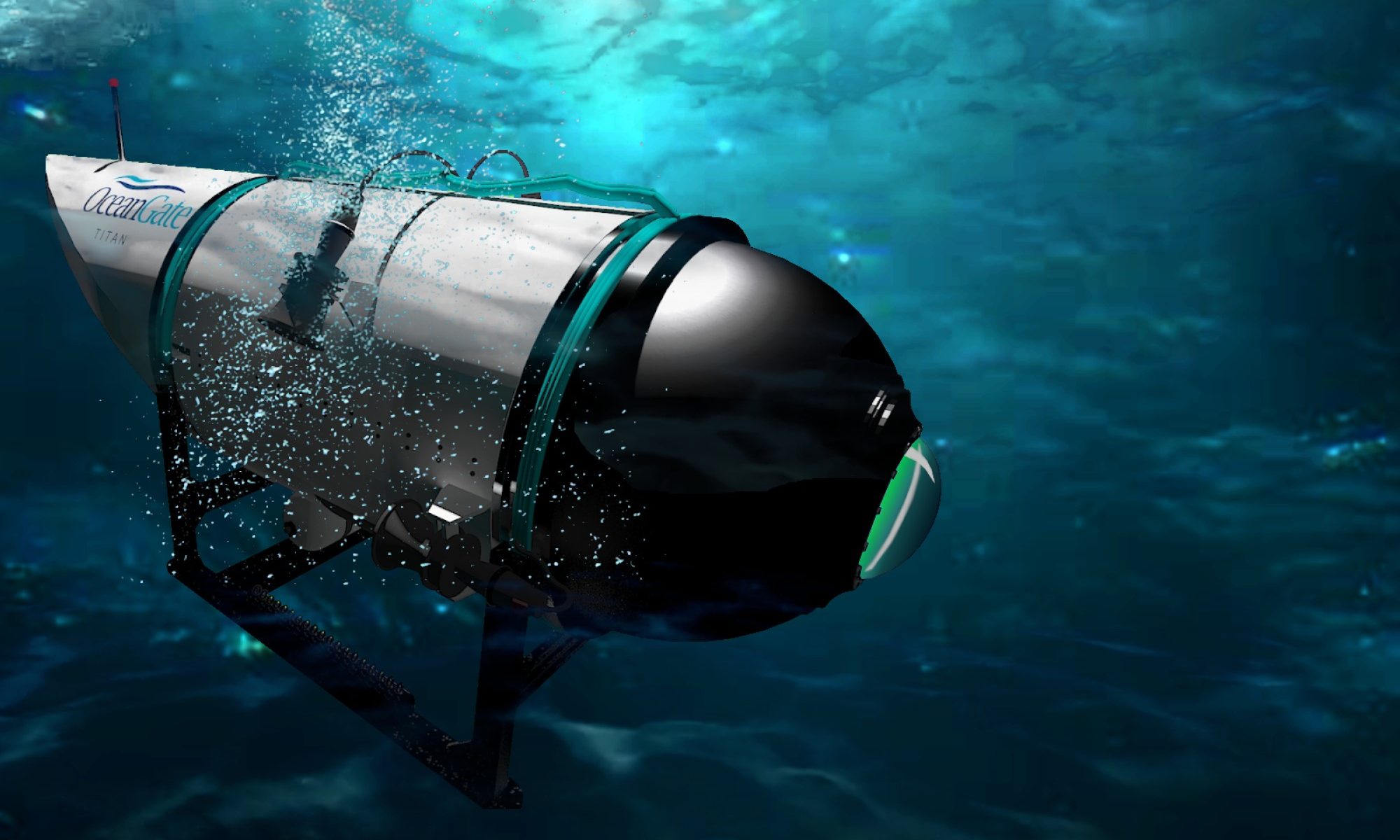

Since it was discovered that the Titan submersible had imploded, many have noted how reckless and irresponsible it was to “MacGyver” a deep-sea submersible. The use of off-the-shelf camping equipment and game controllers seemed dodgy, and everyone now knows it is absolute folly to build a pressure capsule out of carbon fiber. Yet, for years Stockton Rush claimed that safety regulations stifle innovation. Rush’s mindset has been compared to the “move fast and break things” mentality prominent in Silicon Valley. Perhaps there’s something to be learned here. Perhaps we’re hurtling towards similarly avoidable disasters in other areas of science and technology that we will come to see as easily avoidable in hindsight if not for our recklessness.

Since the disaster, many marine experts have come publicly forward to complain about the shortcuts that OceanGate was taking. Even prior to the implosion, experts had raised concerns directly to Rush and OceanGate about the hull. While search efforts were still underway for the Titan, it came to light that the vessel had not been approved by any regulatory body. Of the 10 submarines claiming the capacity to descend to the depths where the Titanic lies, only OceanGate’s sub was not certified. Typically, submarines can be safety rated in terms of their diving depth by an organization like Lloyd’s Register. But as the Titan was an experimental craft, there was no certification process to speak of.

What set the Titan apart from every other certified submarine was its experimental use of carbon fiber. While hulls are typically made of steel, the Titan preferred a lightweight alternative. Despite being five inches thick, the carbon fiber was made of thousands of strands of fiber that had the potential to move and crack. It was known that carbon fiber was tough and could potentially withstand immense pressure, but it wasn’t known exactly how repeated dives would impact the hull at different depths, or how different hull designs would affect the strength of a carbon fiber submarine. This is why repeated dives, inspections, and ultrasounds of the material would be necessary before we get a firm understanding of what to expect. While some risks can be anticipated, many can’t be fully predicted without thorough testing. The novel nature of the submarine meant that old certification tests wouldn’t be reliable.

Ultimately, Titan’s failure wasn’t the use of carbon fiber or lack of certification. There is a significant interest in testing carbon fiber for uses like this. What was problematic, however, was essentially engaging in human experimentation. In previous articles I have discussed Heather Douglas’s argument that we are all responsible for not engaging in reckless or negligent behavior. Scientists and engineers have a moral responsibility to consider the sufficiency of evidence and the possibility of getting it wrong. Using novel designs where there is no clear understanding of risk, where no safety test yet exists because the exact principles aren’t understood, is reckless.

We can condemn Rush for proceeding so brashly, but his is not such a new path. Many of the algorithms and AI-derived models are similarly novel, their potential uses and misuses are not well-known. Many design cues on social media, for example, are informed by the study of persuasive technology, employing a limited understanding of human psychology and then applying it in a new way and on a massive scale. Yet, despite the potential risks and a lack of understanding about long-term impacts on a large scale, social media companies continue to incorporate these techniques to augment their services.

We may find it hard to understand because the two cases seem so different, but effectively social media companies and AI development firms have trapped all of us in their own submarines. It is known that humans have evolved to seek social connection, and it is known that the anticipation of social validation can release dopamine. But the effects of gearing millions of people up to seek social validation from millions of others online are not well known. Social media is essentially a giant open-ended human experiment that tests how minor tweaks to the algorithm can affect our behavior in substantial ways. It not only has us engage socially in ways we aren’t evolutionary equipped to handle, but also bombards us with misinformation constantly. All this is done on a massive scale without fully understanding the potential consequences. Again, like the carbon fiber sub these are novel creations with no clear safety standards or protocols.

Content-filtering algorithms today are essentially creating novel recommendation models personalized to you in ways that remain opaque. It turns out that this kind of specialization may mean that each model is completely unique. And this opacity makes it easier to forget just how experimental the model is, particularly given that corporations can easily hide design features. Developing safety standards for each model (for each person) is essentially its own little experiment. As evidence mounts of social media contributing to bad body image, self-harm, and suicide in teenagers, what are we to do? Former social media executives, like Chamath Palihapitiya, fear things will only get worse: “I think in the deep, deep recesses of our minds we knew something bad could happen…God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains.” Like Rush, we continue to push without recognizing our recklessness.

So, while we condemn Rush and OceanGate, it is important that we understand what precisely the moral failing is. If we acknowledge the particular negligence at play in the Titan disaster, we should likewise be able to spot similar dangers that lie before us today. In all cases, proceeding without fully understanding the risks and effectively experimenting on people (particularly on a massive scale) is morally wrong. Sometimes when you move fast, you don’t break things, you break people.