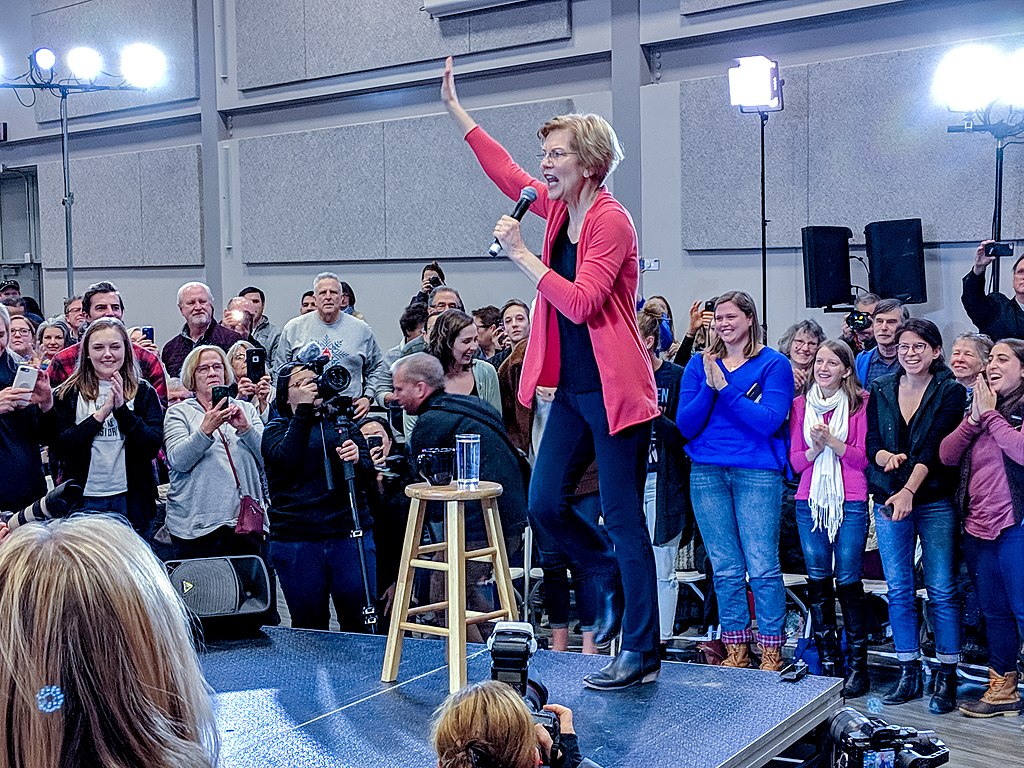

US Senator and presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren has recently proposed a pair of debt relief efforts that aim to address the growing problem of student loan debt in America. The first proposal would cancel “$50,000 in student loan debt for every person with household income under $100,000” (with lesser reductions for those with higher household incomes), while the second aims to help prevent student loan debts from becoming a problem again in the future by eliminating “the cost of tuition and fees at every public two-year and four-year college in America.” Here I want to focus on the ideas behind Warren’s first proposal. Should student debts be forgiven?

Regardless of where one falls on the political spectrum, it is undeniable that mounting student debt is an enormous problem in America. Recent studies have shown that approximately 40 million Americans have student loan debt, and that student debt has become the second-highest category of debt, second only to mortgage debt. Although younger people have the bulk of student debt, individuals from all age ranges have felt the effects, such that “the number of Americans over the age of 60 with student loan debt has more than doubled in the last decade.” There are, of course, consequences to so many people having so much debt: if you are spending a significant amount of your income on repaying student loans then you are going to find it difficult, for example, to buy a house, or car, or save, or invest for your future. It’s also unclear what will happen if a significant portion of those with debt default on their loans, with some economists comparing the student debt situation to the mortgage crisis a decade ago. With student debt being an urgent problem, the idea of addressing it by implementing a debt forgiveness plan might then seem like a good first step.

There are many practical questions to be asked about the implementation of a debt-forgiveness plan like the one Warren proposes (she has, of course, thought about the details). There have been concerns with Warren’s plan, however, that aren’t so much about the dollars and cents as they are about blame and accountability. In answering the question of whether debt should be forgiven we need to first think about who is to blame for it.

A natural place to locate blame is with the students themselves. Here is an example of an argument that one might make for this view:

Those signing up for college know full well what they’re getting themselves into: they know how much college costs, how much they will have to borrow, and generally what that entails for repaying those debts in the future. No one is forcing them to do this: they want to go to college, most likely for the reason that they want a higher paying job that requires a college degree. It may very well be the case that it is difficult to be ridden with debt, but it is debt for which they are themselves accountable. Instead of this debt being forgiven they ought to just work until it’s paid off.

Arguments of this sort have been presented in numerous recent op-eds. Consider, for example the following by Robert Verbruggen at the National Review:

“Where to start with [Warren’s proposal]? With the fact that student loans are the result of the borrowers’ own decisions – often good decisions that increased their earning power? With the fact that people who’ve been to college are generally more fortunate than those who have not? With the fact that this discriminates against people who paid off their loans early, as well as older borrowers who have been making payments for longer?”

In another article, Katherine Timpf similarly claims that student debt should not be forgiven, and that student debt became such a problem only because students were “encouraged to take out loans that they could not afford in the first place.” Curiously, she goes on to claim that while Warren’s debt-forgiveness plan is “a terrible, financially infeasible idea,” it is nevertheless the case that it is a culture that encouraged over-borrowing that is ultimately to blame. It is difficult to make coherent sense of this position: if it is indeed a culture that encourages excessive borrowing that is to blame, then it is hard to see why all the blame should fall to the students.

That student debt is primarily the result of broader societal factors, and not that of bad decision-making, laziness, or unwillingness to “stick it out”, is the driving thought behind many of those who are in favor of debt forgiveness. There are undoubtedly many such factors that have contributed to mounting student debt, but there are typically two that are appealed to most frequently: the skyrocketing cost of tuition and the stagnation of wages. While Warren herself notes that she was able to afford college by working a part-time job, doing so in the modern economy is often very close to impossible. Without independent support it seems that students have little choice but to take out increasingly large loans.

Here, then, is where the ideological heart of the debate lies: those who argue in favor of debt-forgiveness will generally see the blame for the student loan crisis as predominantly falling on societal factors (like increased tuition and stagnated wages), whereas those who argue against it generally see the blame as predominantly falling on the students themselves. Presumably we should assign responsibility where the blame lies, and so depending on who we think is most to blame will determine whether we should implement something like debt forgiveness.

However, we have seen that there is substantial data supporting the view that the student debt crisis is largely attributable to societal factors outside of the control of the students. Furthermore, the thoughts that students are simply “not working hard enough” or “just want a handout” tend to be based on little more than anecdotes and bias (stories of students working multiple jobs just to make ends meet are readily available). This is not to say that students should not be assigned any blame whatsoever for their decisions to go into debt for their educations. However, it does seem that significant contributors to those debts are ones that are outside of a student’s control. As a result, it does not seem that students should be fully blamed for their debts.

Even if this is so, should we think that the best way to take responsibility for those debts is to implement debt forgiveness? As we have seen, some have expressed concerns that forgiving debts would be, in some way, “unfair”. There are two kinds of unfairness that we might consider: first, it might seem to be unfair to those who have already paid off their student loans through years of hard work; second, it might seem to be unfair to those who have to pay for someone else’s debt – Warren’s proposal to finance her debt forgiveness plan, for example, is to generate funds from a tax increase on the extremely wealthy, and one might think it unfair that these individuals should have to cover the debts of someone else. Would a debt-forgiveness proposal be unfair in these ways, and if so, is that good enough reason to say that it shouldn’t be implemented?

While these concerns about fairness might seem like appealing reasons to reject debt forgiveness, upon closer inspection they do not stand up to scrutiny. Consider the first worry: if a debt forgiveness plan is implemented it will indeed be the case that there will be some people who have just finished paying off their debt prior to the policies taking effect and so will not be able to take advantage of their debt being forgiven. It would then seem unfair to privilege one group over another, where the only relevant difference is that the former took on their debt later than the latter. But it is hard to see why this should result in not having any debt forgiveness at all: the argument that “well if I don’t get it, they shouldn’t either!” does not solve any problems. This is not to say that such unfairness should not be addressed at all – perhaps there could be some kind of reimbursement of those who paid off debt before it was forgiven – but it does not seem like a good enough reason to not offer any debt forgiveness to anyone. The second worry similarly fails to hold much water: unless someone takes issue with the idea of taxation in general, then there does not seem to be anything particularly unfair about having the extremely wealthy pay more to aid others.

There are, of course, many factors to take into consideration when considering something like a debt-forgiveness plan, and Warren’s plan in particular. Regardless, it seems that given the severity of the student debt problem, and that the factors that contributed to the problem are largely out of the control of the students themselves, that the responsibility for student debt cannot fall solely on the students themselves.