This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

People often support policies that lessen the harms others experience. For instance, proponents of abortion rights often argue that banning abortion does not eliminate abortions, it only makes them unsafe. Some high school sex education programs provide condoms to students to curb the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. Although traditionally alcohol is banned in homeless shelters, some have shifted to a “wet” model allowing residents to use alcohol and in some cases even prescribing alcohol. The rationale here being that it is easier to get one’s sobriety under control in a managed environment and when one has shelter at night.

More recently, some have considered the role harm reduction may play in addressing the U.S. opioid epidemic. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 93,655 Americans died of drug overdoses in 2020, a 30% increase from 2019, and a further 107,622 died of overdose in 2021. One of the leading contributors to this spike in deaths is the increased presence of fentanyl. Because of its potency, lower cost, and addictive potential, fentanyl is often mixed with other powdered drugs or sold in their place. As a result, people who unknowingly consume fentanyl may accidentally overdose, not realizing the strength of the drug they are consuming.

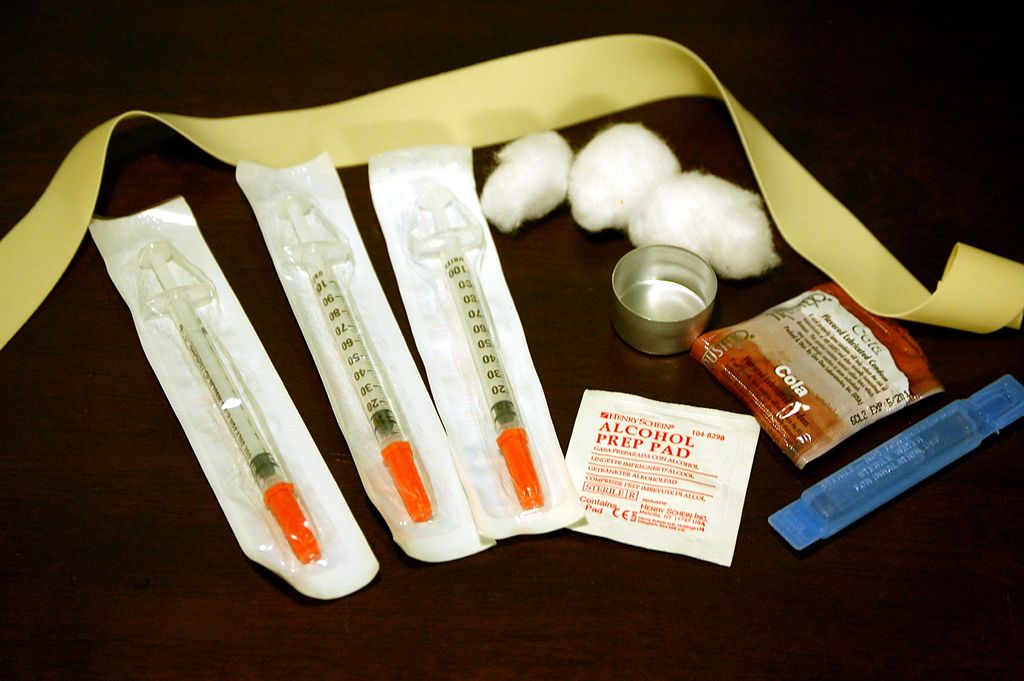

In response, policy makers have been taking measures to reduce the risk of harm fentanyl poses. For instance, although once labeled as “drug paraphernalia” lawmakers across the U.S. have worked to decriminalize fentanyl test strips, hoping to help drug users avoid fentanyl. Some have called for further steps including the creation of Supervised Injection Facilities (SIFs). At these facilities, individuals are permitted to bring in and consume drugs. They are then provided with the means to use these drugs as safely as possible; they receive clean needles, alcohol pads to sterilize injection sites, and medical staff remain on standby to monitor for potential signs of overdose. Additionally, staff can help secure access to resources such as addiction counseling and treatment. The idea is to reduce overall harm by ensuring that those who would otherwise use drugs in public are instead in a private, controlled space with access to resources which can help secure their long-term health. OnPointNYC, the organization running the SIFs, reports they have intervened in 848 overdoses on site and zero deaths have occurred in 68,264 uses.

SIFs, however, are not popular in the U.S. Although other locales have considered opening SIFs, New York City contains the only two officially operating in the U.S. – one in East Harlem and one in Washington Heights. However Representative Nicole Malliotakis of New York’s 11th District has called on the Justice Department to shut down “heroin shooting galleries that only encourage drug use and deteriorate our quality of life.” Pennsylvania’s state senate recently passed a bill banning SIFs by a 41-9 margin. Senator Christine Tartaglione, a Democrat from Philadelphia, stated that her “constituents do not want safe injections site in the neighborhood” and claimed that these sites “enable addiction… [and] we should be in the business of giving these folks treatments.”

These, and other potential objections, warrant further examination. For the purposes of this discussion, I want to consider arguments against harm reduction in the context of SIFs. However, in doing so, these reflections may lead to some insight about harm reduction arguments in other contexts.

One might object to SIFs because they appear to publicly endorse illegal behavior. Yet we may have reason to find this reason uncompelling – the law and morality often diverge. To oppose SIFs because the drugs consumed there are illicit is to merely pass the buck. Why should we regard the use of particular drugs morally objectionable? Why prefer a policy of abstention to moderation? Our focus is better placed on arguments that target SIFs themselves.

The claims by public figures quoted earlier suggest that SIFs fail to prevent harm and instead increase it. There seem to be two purported reasons for this. First, that SIFs enable or even promote drug addiction. Second, that SIFs lead to a deterioration of the surrounding area, encouraging drug users to occupy it, which leads to drug dealing, public drug use, and further threats to the local community.

The available data, however, does not support these arguments. Researchers have found that SIFs lead to lower rates of overdose and decreases in infectious disease rates among drug users. So, SIFs appear to lessen harm to addicts, at least in the short term. Further, SIFs do not seem to impact local crime rates, and, at worst, have no impact on public drug use and needle litter (though there is some evidence that they reduce both).

There is an intuitive argument that these facilities will deteriorate neighborhoods by drawing in drug dealers – the supply may seek out the demand. However, support for this claim is primarily anecdotal. Further, while narcotics arrests have increased in New York neighborhoods with SIFs, these areas now have additional police presence outside of SIFs. It’s at least plausible that an increased police presence is the cause of additional arrests.

Further, there seems to be little, if any, data on the long-term effects of SIFs for overcoming addiction. Perhaps more clarity on long-term consequences of SIFs will come as their impacts are further researched. But currently there seems to be little evidence suggesting they are harmful. They seem to benefit addicts, at least in the short term, and there does not appear to be conclusive evidence that they harm the surrounding community.

But perhaps considering only the consequences misses the point. As I have argued elsewhere, sometimes the consequences of a policy do not seem to matter in the face of other moral objections. Consider, for instance, someone arguing that making cannibalism illegal just produces additional harms – it pushes the market for human meat into the underground, making regulation and oversight impossible, harming both the producers and consumers of human meat. Thus, this person concludes that legalizing cannibalism and regulating human meat consumption would make things safer.

These points, however, fail to resonate as objections to prohibiting cannibalism. This is because harm is just one factor (if even a factor) behind cannibalism’s illegality. Part of the reason why we have laws is to express our attitudes towards a behavior. In this case, eating human flesh simply seems deeply morally wrong to us.

Following this logic, the opponent of SIFs could argue that there is something morally objectionable in drug use, even if SIFs do reduce harm in the long run. That explanation could come in various forms. For instance, in the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, Immanuel Kant argues that someone who refuses to develop their talents acts immorally by disrespecting her own humanity – she has a potential that she is ignoring in favor of seeking pleasure. Alternatively, one might ground an objection to drug use in virtues. Given the long-term risks associated with drug use, one who regularly uses may fail to demonstrate the virtue of prudence. Thus, one might argue that, if drug use is morally wrong, then facilitating it via SIFs would make one complicit in wrongdoing.

Even if one can give a compelling argument that drug use is in some way immoral (although this may be difficult given the disease model of addiction) there are hurdles this explanation must overcome. Namely, it is unclear whether these concerns are the proper basis of legislation. The government has, at best, a limited prerogative to promote virtue, at least in a society with robust individual rights to self-determination. Further, given the sheer scale of deaths from drug overdoses in the United States, it seems more plausible that reducing harms by participating in or facilitating wrongdoing is a lesser evil than continuing with a status quo that results in tens of thousands of deaths a year. And even still, it is not clear that facilitating a wrong behavior for the sake of minimizing harm is itself wrong.

Opponents of SIFs seem to have two rhetorical options available to them. They may argue that SIFs do not, in fact, reduce harm. But this claim has a tenuous relationship to current data. Alternatively, they may argue that even if they do reduce harms, SIFs are ultimately unjustifiable for moral reasons. There is more flexibility in developing arguments of this nature, but there are still serious theoretical difficulties one must resolve even if they can give a plausible argument for drug use’s immorality. Perhaps this is why opponents of SIFs couch their arguments in terms of the consequences of SIFs, even when they lack the data to support these claims.

Ultimately, if OnPoint’s figures are accurate, SIFs show great promise at limiting deaths from overdose. Even if this is their only benefit, this alone should make us pause before rejecting them. While they may only address the symptoms of the opioid crisis in the U.S., we have compelling moral reason to minimize harms while solving the underlying problems behind addiction.