The Internet Archive recently lost a high-profile case. Here’s what happened: the Open Library, a project run by the Internet Archive, uploaded digitized versions of books that it owned, and loaned them out to users online. This practice was found to violate copyright law, however, since the Internet Archive failed to procure the appropriate licenses for distributing e-books online. While the Internet Archive argued that its distribution of digital scans of copyrighted works constituted “fair use,” the judge in the case was not convinced.

While many have lamented the court’s decision, others have wondered about the potential consequences for another set of high-profile fair use cases: those concerning AI models training on copyrighted works. Numerous copyright infringement cases have been brought against AI companies, including a class-action lawsuit brought against Meta for training their chatbot using authors’ books without their permission, and a lawsuit from record labels against AI music-generating programs that train on copyrighted works of music.

Like the Internet Archive, AI companies have also claimed that their use of copyrighted materials constitutes “fair use.” These companies, however, have a potentially novel way to approach their legal challenges. While many fair use cases center around whether the use of copyrighted materials is “fair,” some newer arguments involving AI are more concerned with a different kind of “use.”

“Fair use” is a legal concept that attempts to balance the rights of copyright holders with the ability of others to use those works to create something new. Quintessential cases in which it is generally considered “fair” when someone uses copyrighted materials include criticism, satire, educational purposes, or other ways that are considered “transformative,” such as in the creation of art. These conditions have limits, though, and lawsuits are often fought in the gray areas, especially when it is argued that the use of the material will adversely affect the market for the original work.

For example, in the court’s decision against the Internet Archive, the judge argued that uploading digital copies of books failed to be “transformative” in any meaningful sense and that doing so would likely be to the detriment of the original authors – in other words, if someone can just borrow a digital copy, they are less likely to buy a copy of the book. It’s not clear how strong this economic argument is; regardless, some commentators have argued that with libraries in America facing challenges in the form of budget cuts, political censorship, and aggressive licensing agreements from publishers, there is a real need for the existence of projects like the Open Library.

While “fair use” is a legal concept, there is also a moral dimension to the ways that we might think it acceptable to use the work of others. The case of the Internet Archive arguably shows how these concepts can come apart: while the existing law in the U.S. seems to not be on the side of the Open Library, morally speaking there is certainly a case to be made that people are worse off for not having access to its services.

AI companies have been particularly interested in recent fair use lawsuits, as their programs train on large sets of data, much of which is used without permission or a licensing agreement from the creators. While companies have argued that their use of these data constitutes fair use, some plaintiffs have argued they violate fair use law, both in terms of not being sufficiently transformative, and in terms of competing with the original copyright holder.

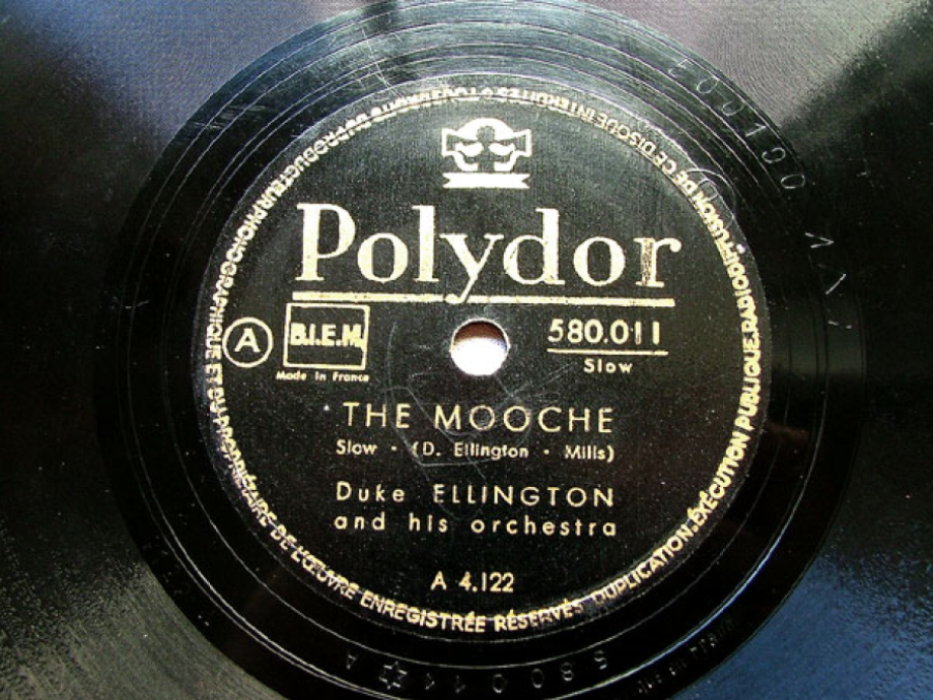

For example, some music labels have argued that music-generating AI programs often produce content that is extremely similar, or in some cases identical to existing music. In one case, an AI music generator reproduced artist Jason Derulo’s signature tag (i.e., that time when he says his name in his songs so you know it’s by him), a clear indication that the program was copying an existing song.

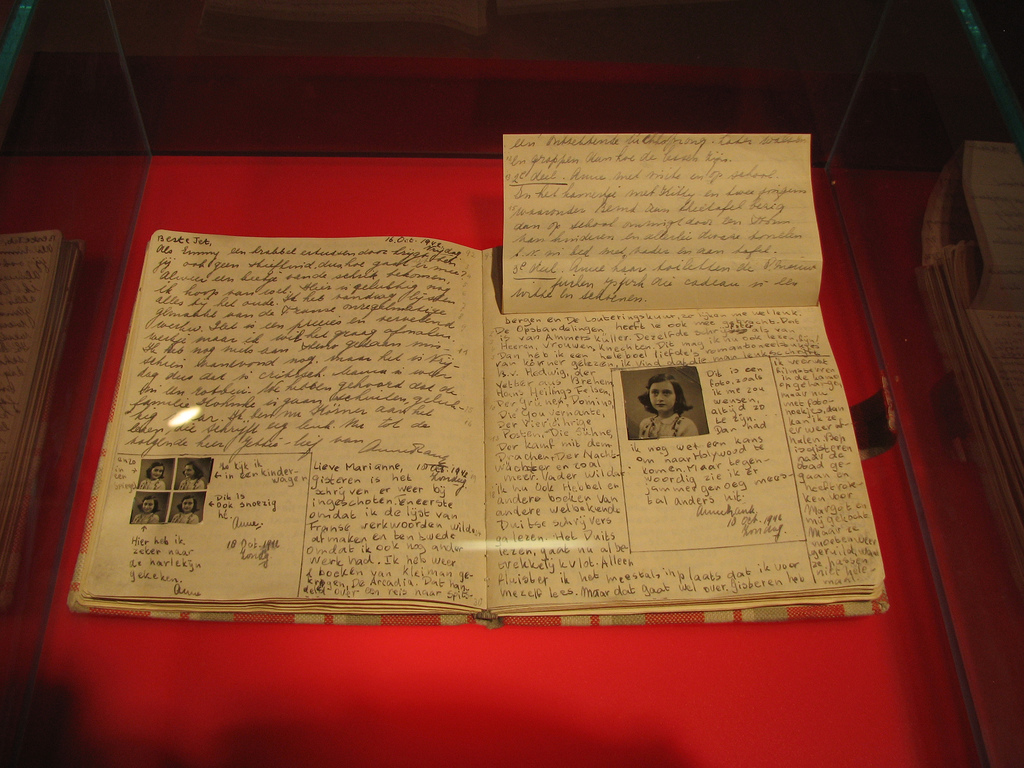

Again, we can look at the issue of fair use from both a legal and moral standpoint. Legally, it seems clear that when an AI program produces text verbatim from its source, it is not being transformative in any meaningful way. Many have also raised moral concerns around the way that AI programs use artistic materials, both around work being used without permission, as well as in ways that they specifically object to.

But there is an argument from AI defenders around fair use that has less to do with what is “fair” and how copyrighted information is “used”: namely, that AI programs “use” content they find online in the same way that a person does.

Here is how such an argument might go:

-There is nothing morally or legally impermissible about a person reading a lot of content, watching a lot of videos, or listening to a lot of music online, and then using that information as knowledge or inspiration when creating new works. This is simply how people learn and create new things.

-There is nothing specifically morally or legally significant about a person profiting off of the creations that result from what they’ve learned.

-There is nothing morally or legally significant about the quantity of information one consumes or how fast one consumes it.

-An AI is capable of reading a lot of content, watching a lot of videos, and listening to a lot of music online, and using that information as knowledge or inspiration when creating new works.

-The only relevant difference between the way that AI and a person use information to create new content is the quantity of information that an AI can consume and the speed at which it consumes it.

-However, since neither quantity nor speed are relevant moral or legal factors, AI companies are not doing anything impermissible by creating programs that use copyrighted materials online when creating new works.

Arguments of this form can be found in many places. For example, in an interview for NPR:

Richard Busch, lawyer who represents artists who have made copyright claims against other artists, argues: “How is this different than a human brain listening to music and then creating something that is not infringing, but is influenced.”

Similarly, from the blog of AI music creator Udio:

Generative AI models, including our music model, learn from examples. Just as students listen to music and study scores, our model has “listened” to and learned from a large collection of recorded music.

While these arguments also point to the originality of the final creation, a crucial component of their defense lies in how AI programs “use” copyrighted material. Since there’s nothing inherently inappropriate about a person consuming a lot of information, processing it, getting inspired by it, and producing something as a result, nor should we think it inappropriate for an AI to do the same things.

There have, however, been many worries raised already with inappropriate personification of AI, from concerns around AI being “conscious,” to downplaying errors by referring to them as “hallucinations.” In the above arguments, these personifications are more subtle: AI-defenders talk in terms of the programs “listening,” “creating,” “learning,” and “studying.” No one would begrudge a human being for doing these things. Importantly, though, these actions are the actions of human beings – or, at least, of intelligent beings with moral status. Uncritically applying them to computer programs thus masks an important jump in logic that is not warranted by what we know about the current capabilities of AI.

There are a lot of battles to be fought in terms of what constitute truly “transformative” works in lawsuits against AI companies. Regardless, part of the ongoing legal and moral discussions will undoubtedly need to shift their focus to new questions about what “use” means when it comes to AI.