This week the European Space Agency made a proposal that the Moon get its own time zone. Currently the Moon has no specific time, with the recorded time coinciding with the nation that launched the mission. However, there has been a steady increase in interest in the Moon with Japan, India, China, the United Arab Emirates, and America all sending probes of different sorts. With plans by the U.S. to send a crew to the moon by 2025 and China by 2030, it has been argued that there is a growing need to create a standardized Moon time in order to make coordination and cooperation amongst various nations (and corporations) easier. As we take yet another step closer to some sort of occupation, sticky questions and daunting concerns regarding lunar colonization abound.

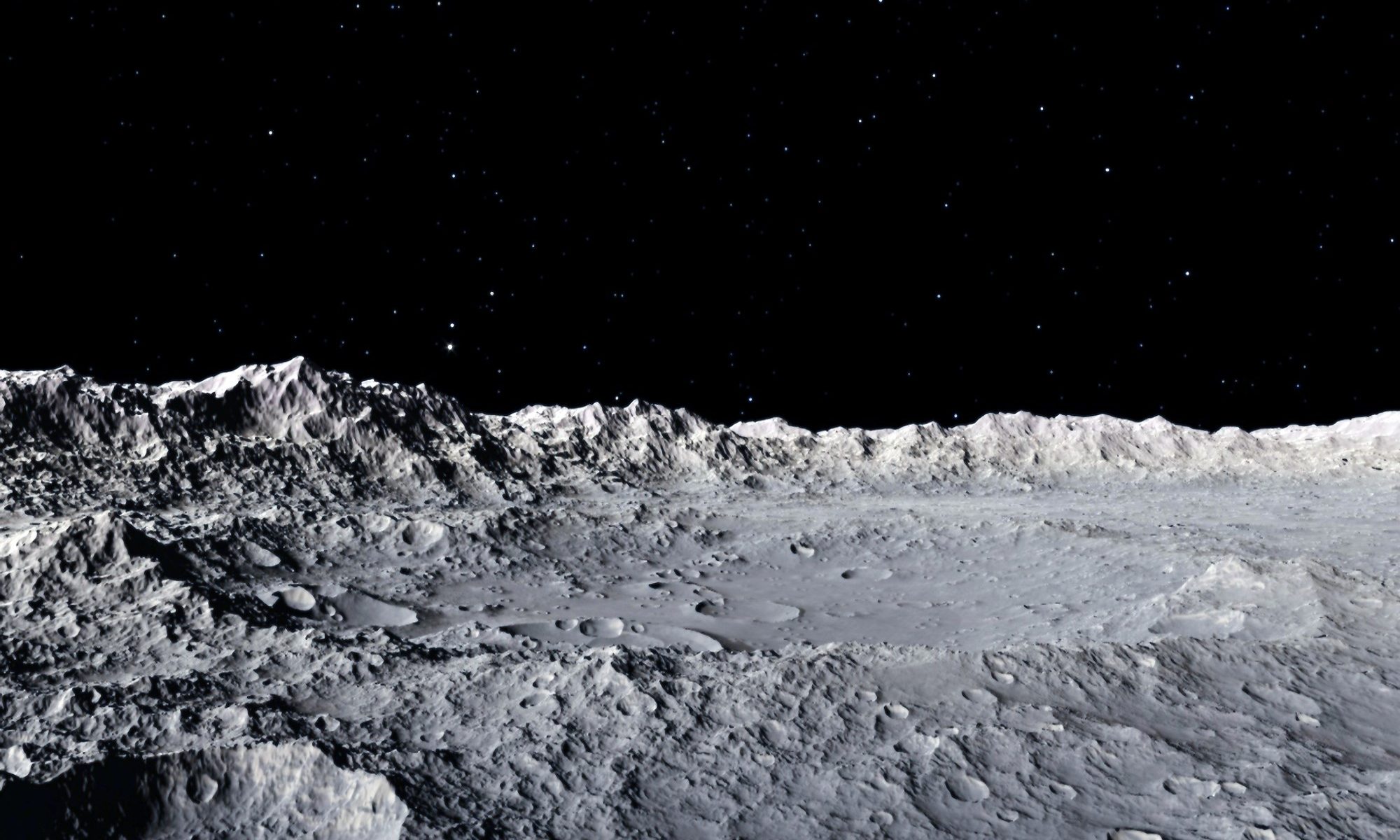

Clearly, a space race will only hasten human efforts to colonize the Moon. It was recently reported that NASA is increasing its efforts to mine metals and locate fuel on the Moon — a response, in part, to China’s lunar mining efforts. NASA administrator Bill Nelson recently warned that China could establish a foothold on the Moon and attempt to dominate the most resource-rich locations and exclude other nations. (There are, for instance, only a few areas near the south pole of the Moon that are thought to be adequate for harvesting water.) Also, there are concerns that Chinese lunar infrastructure could be used to interfere with communication. Given this, it may not be long before a permanent occupation of the lunar surface – with equipment and infrastructure – begins.

A number of scholars have made the argument that we have an ethical obligation to begin colonizing space. They will note issues like overpopulation and the destruction of natural resources on Earth as reasons we need to begin looking elsewhere to habitate. Gonzalo Munevar has argued that we have an obligation to colonize space as a means of preventing the extinction of life on Earth and to make deflecting asteroids easier. I’ve also previously mentioned Michael Mautner’s argument that we are obligated to “plan for the propagation of life.” Nevertheless, there are a host of concerns with these propositions.

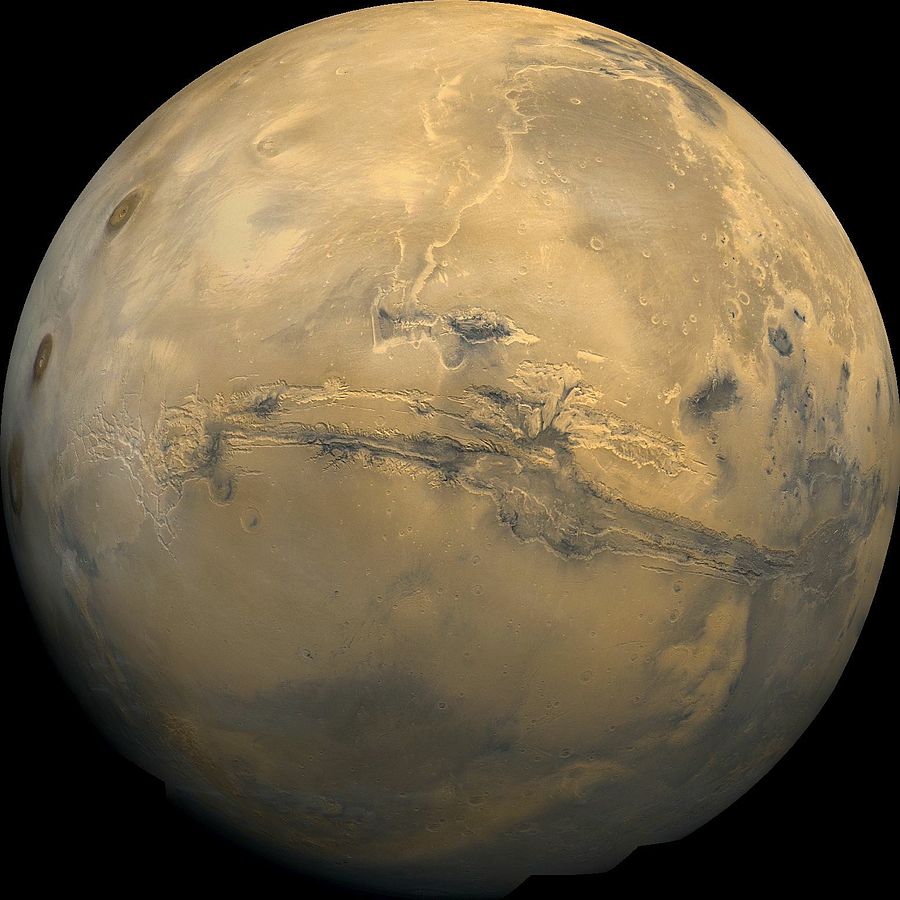

Many of these arguments are environmental in nature. For example, in the discussion about the colonization of Mars, scholars like Linda Billings have argued that it would be wrong to contaminate a potentially habitable planet and to transport life to it. Of course, the Moon does not have life, nor is thought to be capable of supporting it. Still, some argue that celestial objects such as the Moon or asteroids do constitute an environment that we may have certain ethical obligations to it. A paper by Daniel Pilchman outlines an argument using the work of W. Murray Hunt’s “Are Mere Things Morally Considerable?” He questions whether valuing life is morally arbitrary and argues that we ought to instead value existence itself. If this is correct, it’s possible we should consider the rights of the Moon to exist as it is. Further, Pilchman considers the possibility that our desire to mine asteroids (and by extension the Moon) constitute a failure of virtue on our part. The best people, so the argument goes, are those who live with a sense of awe, reverence, and care towards celestial objects rather than seeing them merely as means to our ends.

Unfortunately, these arguments may very well come to naught. Vast investments have been (and are being) made and with the competition forming between the private sector and rival nation states. Some form of lunar colonization seems inevitable.

The most practical question might not be should we colonize the moon, but how should we go about it – what is the most ethical way we can begin to plan and what are the worst outcomes to avoid?

For example, what justifications should we seek if someone stakes a claim to a region on the moon with resources? The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 claims that no nation may claim ownership of the Moon, and the Moon Treaty of 1979 forbids harvesting resources on the Moon. But these treaties may be well past their due date.

Pilchman notes that territorial claims to regions of space could follow the “original appropriation argument” which takes its lead from John Locke. According to Locke, to claim ownership of “the commons” someone must mix their labor with the land, leaving enough for others and only appropriating what can be reasonably used without it going to waste. So long as a nation or corporation invests time and effort and doesn’t go overboard in appropriation, they would be morally justified in claiming parts of the Moon as their private dominion.

We should, however, be concerned about what a system like this incentivizes space actors to do.

Despite the “no spoilage” proviso, it would incentivize a “first dibs” situation where the first groups to the Moon claim the best spots. As a recent Bloomberg article puts it, “The advantage extends beyond first dibs on what there is to be dug up. There’s also a role in establishing norms and precedents for how space operations should be conducted.” Not only would this create an inequitable situation for nations that can’t afford lunar excursions, it will incentivize a space race that could see groups aggressively protecting their stakes.

While international treaties ban the use of weapons of mass destruction in space, there are already serious concerns about the effects that warfare would have on space, including the destruction of GPS networks. “Outer space is not a wrestling ground,” said a spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy, “The exploration and peaceful uses of outer space is humanity’s common endeavor and should benefit all.” Nevertheless, Chinese satellites have even been designed with grappling arms capable of moving other satellites in orbit. The more infrastructure that exists in space, the greater the investment, the greater the incentive will be to weaponize space to protect them. This could quickly escalate in ways that we might not want if we don’t get out ahead of these issues of ownership now. Similarly, the mining of resources from outer space has the potential to profoundly affect the economy of Earth. For example, one asteroid has been valued at $700 quintillion dollars. It isn’t hard to imagine how much economic upheaval that large scale mining could bring about.

If we don’t take efforts to forestall the worst possible consequences now, we may find that geopolitics will shift in ways that we can no longer anticipate or control. Many will point out the problematic ethical similarities between colonialism on Earth and colonialism in outer space, and with that in mind, it’s worth considering the efforts of the world at that time to avoid warfare, like the Berlin Conference. This is not only because many of the imperial ambitions of the time were primarily focused on resource extraction, but also because of the grave risk of geopolitical conflict. If we don’t start making decisions about these issues now, we may find that our ethical choices are far more limited later.