On January 7th, 2022 David Bennett was implanted with a pig heart. His doctor was not Moreau, but rather Muhammad Mohiuddin, a surgeon at the University of Maryland Medical Center and expert in xenotransplantation – the implantation of animal organs into humans.

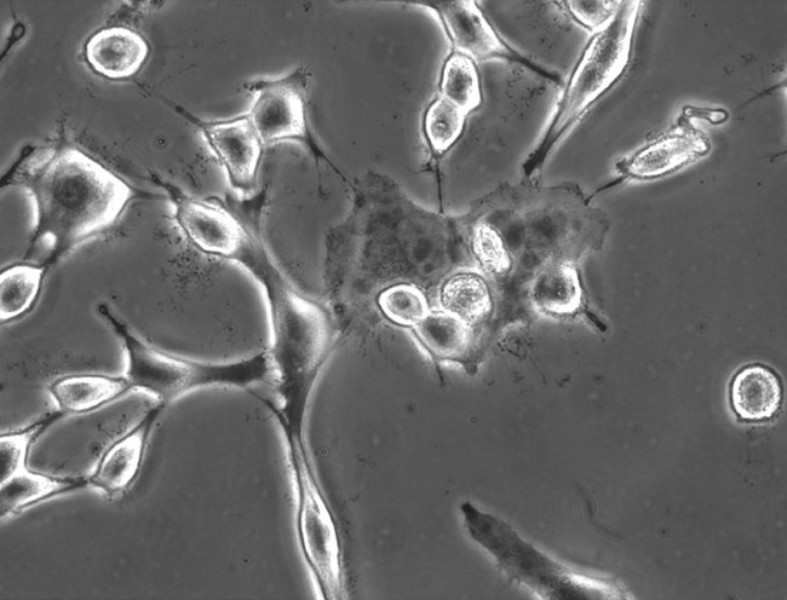

While pig parts have been used medically for decades, such as the use of pig heart valves as replacement valves, the implantation of a whole organ is an incredible clinical achievement. The donor animal is genetically modified and raised in careful conditions to minimize the chance of pathogen transmission and rejection, that is, the human immune system attacking the heart as foreign tissue. Whole organ xenotransplants been performed before, but without effective technology to prevent rejection, results have been bleak.

The life-saving surgery was done under special FDA authorization given the lack of other options. How Bennett will fare long-term remains unclear, and like most transplant patients he will need to take immunosuppressant drugs even with the genetic modifications done to the pig. Transplant patients are followed for both physical and psychological concerns, as the feeling of becoming hybrid or chimera, or taking up aspects of the donor, is well established, and may be especially acute in xenotransplantation. (Regardless of the physiological legitimacy of this feeling.)

The organ donor list is long in America, and the supply of organs short. Xenotransplantation represents a potential lifeline for thousands of patients in need. Nonetheless, as amazing as new xenotransplantation technology is, it comes with longstanding ethical concerns.

Modern medicine heavily instrumentalizes animals, their bodies becoming objects of research and testing, and now harvested for organs. From an animal welfare perspective, xenotransplantation is clearly not good for the pigs – although perhaps not any worse than factory farming. Xenotransplantation research also involves extensive use of non-human primates, especially baboons, as they are considered the best animal model to test the viability of cross-species transplants for humans.

Beyond animals, xenotransplantation research makes use of brain-dead humans as test subjects. Death is a tricky designation, and some people, while deemed dead from the perspective of brain death, are nonetheless biologically stable enough to support a transplant for some period of time. In September of 2021, for example, a genetically modified pig kidney was attached to a brain-dead woman and supported for 54 hours. The idea is that data like this is of more relevance to human recipients than that from baboon trials, although the condition of the test subjects renders it all but impossible to do longer term studies. Such research practices invoke complex questions about human subjects, and the status of brain death. The very idea that the body is declared dead, yet somehow alive enough to test organ transplantation, challenges our intuitions. And for communities for whom the body or the breath are more important in the designation of life and death, brain death is a thin justification for such research.

These research practices may be defensible, but they should be done carefully, with attention to the animal welfare implications, the alternatives, and the expected benefits of xenotransplantation. This ethical question is made more complicated by the empirical fuzziness, for we do not yet know what the clinical payoff might be.

The more sensational ethical concerns of xenotransplantation research come from the ick factor. One can all too easily imagine Jeff Goldblum informing Dr. Mohiuddin that he is playing God, and that humans should stay well away from the creation of chimeras.

From a scientific perspective, this is tricky. Humans are never pure. Not only are humans, like all organisms, a cobbled together pile of old parts assembled by evolution, but even during the course of our life we are a blend of different species. Just ask the 100 trillion bacteria living inside your gut.

Nonetheless, this is all at least “natural,” whereas xenotransplantation most certainly involves some kind of additional level of “unnatural” intervention. There are two ways, I believe, we can make this concern more precise.

The first involves an express embrace of the sacred or the natural. For example, a Christian theological perspective in which the body is explicitly treated as sacred, may provide clear grounds for ethical objection to xenotransplantation. This may be an even greater concern in Jewish and Muslim communities with their specific injunctions against the eating of pork, although some Jewish and Muslim religious authorities have been open to uses of porcine parts when clinically necessary.

The limitation of this approach is that it argues against xenotransplantation based on the acceptance of specific religious or spiritual premises, or ontological claims, about what is natural, as opposed to general ethical principles.

The second characterization of the concern is about the implied values. Xenotransplantation embraces a conception of medicine such that all research and interventions are okay as long as they are ultimately in service of prolonging life. A more humble ethical framework, one that is more accepting of death, may not value xenotransplantation to the same extent. The Harvard political philosopher Michael Sandel has developed a perspective of giftedness regarding intervention. His idea is that we should not strive for mastery of every aspect of our biology, but should be open to the arbitrariness of life as something which makes it worth valuing. Sandel, to be clear, is not against healing, and believes that healing disease helps our natural capacities flourish. But where we draw the line is fuzzy, and one possible objection to xenotransplantation is that it fails to appropriately acknowledge the messiness of life and the ways to cope with that, and instead is highly technocratic, seeking mastery and intervention. (At the expense of animal life.)

Finally, xenotransplantation is new, expensive, and technologically demanding, and ethical issues will no doubt arise in the specifics of implementation. How should it be handled with insurance? How should patenting work? Who deserves access to these organs? For instance, concerns have been raised about Bennett who was guilty of a 1988 stabbing. Organ donation in the United States is administered by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and policies are in place to facilitate the equitable distribution of organs. Although even these are imperfect, and wealthier, better-connected patients can use strategies like signing up at multiple transplant centers to receive organs faster. How whole organ xenotransplantation will fit into the existing scheme is not yet clear, but should be done in a way that preserves as far as possible equity of organ donation.

Personally, I worry an overly restrictive ethical response would be premature, as we are still in the research stage with xenotransplantation and therefore have an unclear decision to make from an outcome perspective. David Bennett’s case may be important for public perception, but as a single instance, it is limited in how scientifically informative it can be. Nonetheless, we should continue a parallel conversation about animal welfare, research ethics, and highly interventionist medicine. And above all, we should avoid celebrating a medical marvel as an ethical one without careful reflection.

Note: David Bennett died March 8th, 2022, two months after the procedure.