Where Does the Confederate Battle Flag Belong Today?

Political pressure is mounting for the removal of the Confederate battle flag that flies on the state grounds of South Carolina in the wake of the Charleston Church shooting. In recent years, public debate over the flag that symbolizes racism to some and heritage to others has intensified. The divergent views towards the flag inflamed intense public dialogues about racism, culture and history ever since the mid-1950s. Under this circumstance in 1993, United States Senator from Illinois Carol Moseley-Braun claimed “it is a fundamental mistake to believe that one’s own perception of a flag’s meaning is the only legitimate meaning.”

As Moseley-Braun suggested, people should not impose one’s interpretation of the flag to others, and seeking to understand why people are offended by it and why people preserve it are actions that are necessary to take as educated citizens. In order to fully comprehend the implications that the flag gives to a diverse public, understanding the entire history of this symbol would become necessary as people from different backgrounds from a wide range of generations view the flag from a variety of perspectives.

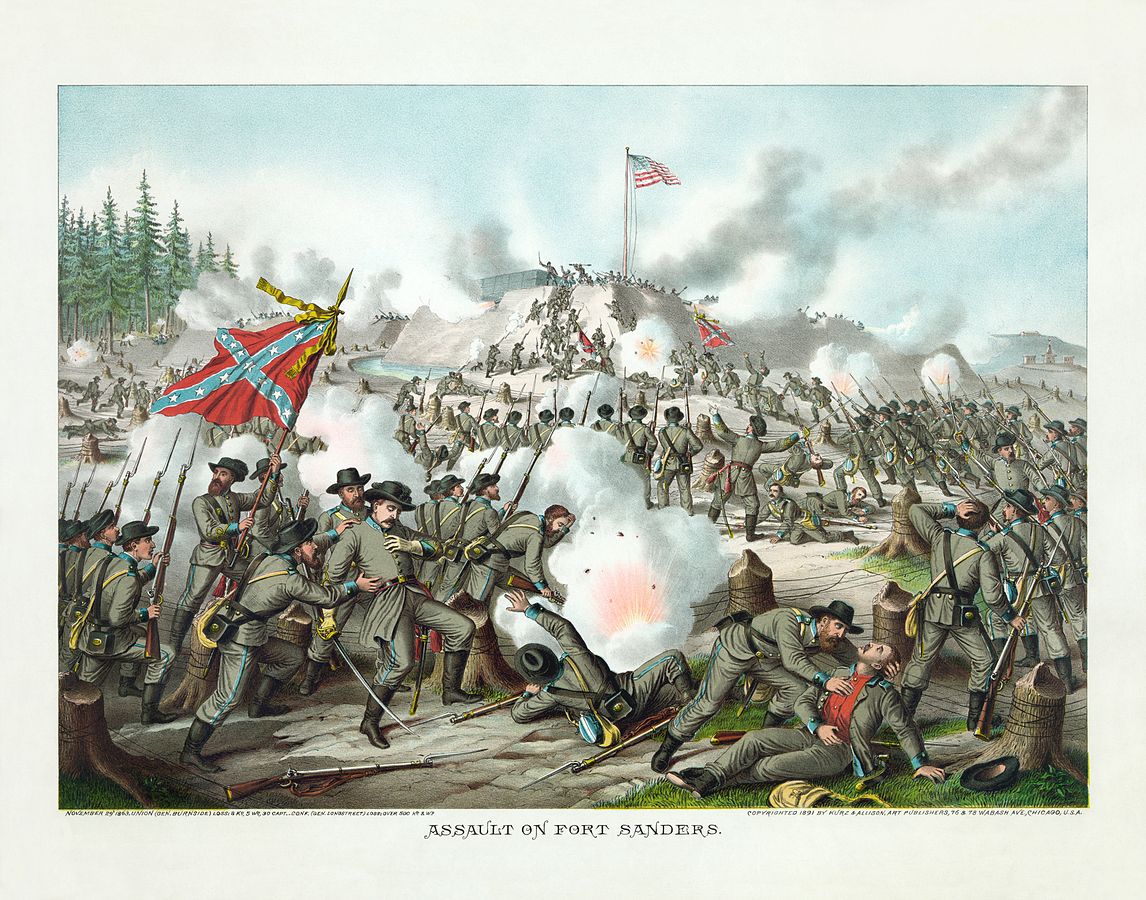

Unlike common belief, during the Civil War the Confederate battle flag did not explicitly symbolize racism nor slavery. Among the southern white population, less than 5% were slave owners, and thus, the majority of the Confederate soldiers did not own slave property. Racism prevailed both in the Union and the Confederacy as both parties did not give African Americans the right to vote and fundamental human rights. In fact, historian James McPherson argues that the main Confederate “cause” of the Civil War was to preserve their country and the legacy of the Founding Fathers, which derived from southern nationalism. As Lincoln recalled in his Second Inaugural Address in 1865, that slavery was “somehow the cause of the war,” the modern debate arguing that the Civil War about slavery, and therefore, the battle flag represents slavery is a mere simplification of history. The war was centralized on the issue on slavery, but one cannot naively generalize that all Confederate soldiers were committed to slavery and supported going to war for that cause.

The history of the flag does not end with the Civil War, but expands after World War II with the rise of the Civil Rights Movement. To many people’s surprise, the proliferation of the Confederate battle flag happened after 1954, when the U.S. Supreme Court declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional via the Brown v. Board of Education case. Although segregation was illegal, many southern states were reluctant to integrate schools. To show their resistance against integration, the Confederate battle flag came back in the public sphere.

The following year of the Brown case, George Wallace, governor of Alabama, raised the flag as part of his “Segregation Forever” campaign and endorsed it as a symbol of resistance. Not only political figures, but also segregationists brandished the flag to contest integration. It was at this time when the flag entered American popular culture as a symbol of opposition to integration, as Jonathan Daniels, editor of Raleigh News & Observer, lamented in 1965 that the flag had become “just confetti in careless hands.”

So, how should governments, corporations and individual citizens cope with a cultural icon that ignites intense debates? One must acknowledge the difference between public and private display of this flag. Public display of the flag (e.g. on the South Carolina state grounds) should be prohibited with the understanding that this flag symbolizes racism for a wide majority of the public. A governmental institution should not naively display a symbol of racism and show innocence in front of people who are offended by it. One must ask: “what would it be like for a Black citizen living in a state where a symbol of racism waves on the state ground?” Confederate flag images can harass or intimidate citizens and the government must not endorse such figure on its public ground. Moreover, the presence of the flag on the state ground excludes and ignores the population who do not honor it.

On the other hand, it is essential to distinguish between the flag as a memorial and the flag as a symbol of exclusion. The Civil War is undeniably a fundamental part of American history and culture, whose events still fascinate many Americans today. The history of the Confederacy is as valuable as the history of the Union, and no one can erase the four years that the two parties had fought. It is necessary to acknowledge that for many southerners, the Confederacy is part of their family history and the flag is a tool to honor their ancestors. Confederate heritage organizations have the right to privately use this symbol with the understanding that explicit use of the Confederate battle flag may offend others who are uncomfortable with it.

We live in a country where people come from different cultures, nationalities, and family backgrounds, and therefore, it is natural that there is a variety of perspectives on how one considers the Confederate battle flag. Many Confederate descendants look at the flag as a symbol of heritage, but this does not make the flag an honorable icon for everyone. A large number of people view the flag as a symbol of racism, but no one can assume that everyone who raises the flag is a racist. However, a governmental institution must consider the negative implications that this icon gives to the public. Even in private settings, no one can naively use this powerful symbol without considering the message that this flag might give to a wide public. In sum, seeking to understand the diverse meanings of the flag and engaging in honest dialogues would lead us to a better understanding of the proper place of the Confederate battle flag in modern day society.

References

Edward Pessen, “How Different from Each Other Were the Antebellum North and South?” American Historical Review 85 (1980): 1119-49.

James M. McPherson, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

John M. Coski, The Confederate Battle Flag: America’s Most Embattled Emblem (Cambridge, MA : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005).

From Outrage to Integration

This post originally appeared on July 20, 2015.

On my way to lunch the other day, about a week after the horrific shootings in Charleston, I found a noose suspended over an otherwise sunny sidewalk. I took it down and threw it away.

I spent the rest of the day distracted. I live outside of Austin, Texas—a liberal enclave if ever there were one. If I’d heard that this had happened elsewhere, I’d have been discouraged, though not surprised. But on one of the main streets in my town? A block from campus? On a breezy, beautiful summer afternoon?

Who would do such a thing?

I don’t know, of course. But if I had to guess, I’d say that it was someone who did it on a dare. Or someone who wanted to be shocking for being shocking’s sake. Or someone trying to get upvotes in some dark corner of reddit. Whoever it was, though, I doubt that I would be pleased to find out. It probably wasn’t the Platonic form of American racism: the Angry Southerner, complete with cut-off t-shirt and muddy boots. Given the demographics here, it was probably someone much like me: white, male, from a middle-class background, raised in a fairly segregated environment, and perfectly polite and pleasant—even to people of color—in various professional circumstances.

And yet this person hung a length of rope from a tree, in a town where you can still visit the slave’s section of the cemetery. How should we—how should I—respond to this act?

I’d like outrage to be sufficient. I’d like it to be enough that I denounce the perpetrator, that I share my anger with my friends, that we complain together about those people.

But it’s not enough. Outrage pushes racism underground; it doesn’t end it. More importantly, outrage doesn’t counteract the effects of racism. When, in the future, my sons encounter reminders that lynchings still happen, they won’t worry about their safety. They’ll never be concerned that someone is angry about their presence in a particular place, or that someone is so upset about “how things are changing” that he wants to place a symbol of death near city center. My sons will—I hope—mourn that this is how things are. Still, they won’t be mourning that this is how things are for them. If that isn’t an advantage, I don’t know what is.

In The Imperative of Integration, Elizabeth Anderson argues that racial segregation leads to three forms of racial injustice: it limits economic opportunity (good jobs tend to be in “white” areas), it enables racial stigmatization (it’s easy to form negative stereotypes about people of color when you rarely encounter them), and it undermines democracy (insofar as lawmakers can ignore the interests of a segment of society). Accordingly, she argues that integration must occur: first, formal integration, which involves repealing laws that lead to inequality; second, spatial integration, ending the de facto segregation of playgrounds and post offices; finally, social integration, where the institutions in which we learn and work are reconfigured to better serve the needs of a diverse populace.

We won’t hear many objections to formal integration. Spatial and social integration, on the other hand, can feel like radical proposals. But if justice is the first virtue of social institutions, then radical solutions are sometimes required. What should we do in a society where some children are—and others aren’t—disadvantaged by accidents of birth? We should actively support policies—at all levels—that reorganize society to counteract the effects of racism, whether that racism is explicit or implicit, conscious or structural, blatant or barely visible.

Frankly, the thought is overwhelming. It’s to our shame, however, that black children enter a world where nooses still hang from branches. It’s time to give direction to our outrage.