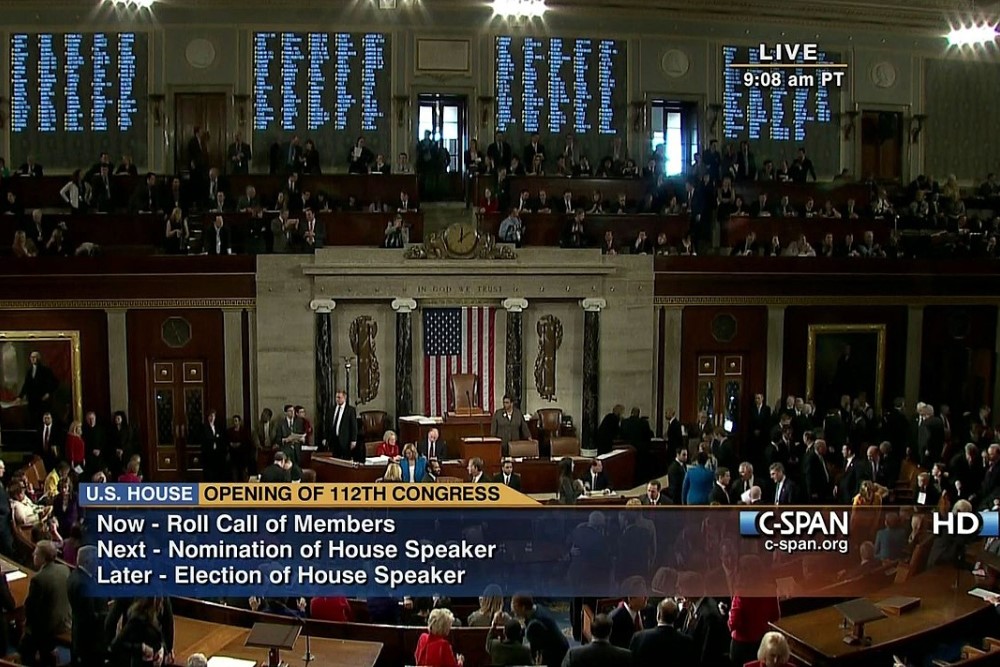

During both of the most recent impeachments, an old argument resurfaced. Afraid of retribution, many spoke out to advocate a way Republican members of Congress could get rid of Trump and keep their own seats. They suggested that the impeachment vote in the House and the Senate should be done in secret. Republican voters would know some Republicans voted to convict, but the blame would be diluted, spread across all 50 or so Republican senators. And so each Republican senator would individually be unlikely to lose his or her seat.

But this raises a question: if it would be good to convict Trump secretly, why not make the votes on all sorts of controversial issues secret? The people would know what laws were passed of course, but no one would be allowed to see committee meetings. No congressional sessions or votes would be broadcast on TV. You would vote in your representatives and then for two, four, or six years, you would simply trust that they voted in the way that was best. Members of Congress could pass legislation that might be unpopular to their constituency, but important for the nation at large. And neither ordinary citizens nor lobbyists could influence the legislative process after election day.

Many, however, are horrified by this idea. Making acts of Congress secret would be akin to government by aristocracy, rule by the elites, not democracy. Transparency is vital because it allows citizens to accurately judge whether their elected representatives are actually representing them instead of simply voting their own interests.

Let’s consider the arguments on both sides here and see if we can develop a better understanding of the issue. What are the benefits of congressional secrecy? And, are the costs to democracy too severe?

The first reason why one might think congressional votes should be secret is because this secrecy would allow Congress to stop acting only along party lines. Congress is extremely partisan nowadays and this hasn’t always been the case. Furthermore, this unwillingness to cross the aisle leads to difficulties in Congress achieving popular political ends. For example, nearly 60 percent of Americans supported Trump being convicted and removed from office after the second impeachment trial. Even more Americans, including 64 percent of Republicans, support stimulus checks. But, no Republican members of Congress voted for Biden’s stimulus check, despite voting for Trump’s. And finally, a majority of Republicans support increasing the minimum wage, but Republican members of Congress vote against it when the issue is raised by Democrats. Voting against political opponents seems to be more important to members of Congress than passing popular legislation.

The fact of the matter is that Congress isn’t beholden to your average voter. Nor even the average voter from their party. Members of Congress are beholden to the partisans of their party because of the primary system. According to a study from the Social Science Research Council, primary voters tend to prefer politically extreme candidates. And if candidates can’t make it past the primaries, it doesn’t matter how popular they would be in the general election. (Some have suggested primaries are responsible for Trump’s nomination.) In any case, if Congressional votes were more often secret, congresspeople could give lip service to extremism in the primaries while looking to what’s best for the country when they actually vote. Those extreme partisans wouldn’t know who betrayed them. Thus, legislation that is broadly popular, but not popular among extreme partisans, could be passed and perhaps we’d be better off.

But, partisans and primaries aren’t the only reason Congress doesn’t pass popular legislation. Another problem congressional secrecy, especially in committee meetings, could solve is the influence of lobbyists and donors. As I have written elsewhere, money in politics is a seriously corrupting influence. Lobbyists and donors frequently control the legislative agenda. But, again, this hasn’t always been the case. The number of lobbyists skyrocketed in the 1970s with the passage of so-called “Sunshine Laws” meant to improve government transparency. Some of these are good: Freedom of Information Act requests allow the people to have access to a great deal of information about the operation of government that would be otherwise hidden from them. But, they also allowed lobbyists to flow in from the lobby through the previously closed doors of committee meetings. As is argued by the Congressional Research Institute (a think tank, not part of Congress), these laws “enormously enhanced the ability of ‘outside’ lobbyists and powerful entities to influence the legislative process,” and so they claim “all legislative transparency overwhelmingly benefits special interests and the powerful.”

Think of it this way: before, lobbyists and donors could monitor how congressional votes shook out. If particular members of Congress voted how the donors wanted, they would get more campaign donations, and if not, they wouldn’t. This influence has always been around. But since the passage of the Sunshine Laws, lobbyists can monitor the entire legislative process: they can write the legislation, follow along with congressional committee meetings to make sure no revisions are made they don’t like, and display their approval or disapproval to members of Congress throughout the process. Of course, ordinary citizens can do this too, but they tend not to have the resources to lobby as powerfully as massive corporations or billionaires. If the relevant “Sunshine Laws” were reversed, many of these problems would go away, and if congressional votes were made secret too, lobbying would become a very bad investment. Donors could spend money on lobbying and campaign donations and hope that the legislator feels pressured by it, but they would never be sure if it worked. Thus, the influence of money in politics would be diminished.

However, there remains an enormous counter-argument to making the acts of Congress secret. I have been making a very utilitarian case for secrecy. It would achieve better results for the American people. But that may not be the only thing that matters. One might argue that the ends aren’t the only things that matter; the means do too. Making the acts of Congress secret would allow lawmakers to ignore the interests of the people in favor of their own opinions and values. It would allow members of Congress to lie to the people about how they voted with little to no consequence. Perhaps transparency should be considered a virtue such that if maintaining transparency means lobbyists and donors get their way, so be it.

One might say getting something they consider important, like removing Trump from office, or getting stimulus to the people, or raising the minimum wage, isn’t worth the cost of allowing Congress to be unbeholden to voters. Is a democracy led by representatives who can ignore the voters really a democracy at all? Many political philosophers, like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, have argued that government derives its power from the consent of the governed. One might hold that doing what the people want, even if it’s wrong, is more important than doing right, if it means ignoring the will of the people. A government that doesn’t act for the people may not be much of a government at all. And why should we think representatives know better than the population at large? They are only human. And more than that they are an unrepresentative sample of the country, being more white, more male, older, and wealthier than the American population.Thus, on this view, making the acts of Congress secret is untenable: it is valid only according to a consequentialist framework and anyone who disagrees with such a framework will abhor the fact that legislators will be incentivized toward dishonesty and away from democratic principles. As Aristotle wrote in the Nicomachean Ethics, to act “at the right times, with reference to the right objects, towards the right people, with the right motive, and in the right way, is what is both intermediate and best, and this is characteristic of virtue,” nothing more, nothing less. This is a far higher standard than simply weighing the consequences and one we should strive for.

Making the acts of Congress secret would be an enormous change and not one to be taken lightly. As I have shown, your thoughts on this issue can vary significantly based on which moral framework you follow. The case, at least in the short term, is clear for the consequentialist. But for the virtue ethicist or deontologist, things are far murkier. Answering this question, as with many moral questions requires us to consider which of our values cannot be crossed? Which do you value more, if one has to be sacrificed: transparency and democracy, or the people’s welfare? In any case, something needs to be changed so that the problems of political partisanship and the influence of money in politics are resolved. Making the acts of Congress may be one solution but there are surely others. Perhaps we should reform the primary system. Perhaps we should overturn Citizens United to diminish the power of donors and lobbyists. The number of ethical solutions is only limited by our creativity, something which must be trained by continual practice and reflection.