For many, the idea of paying great sums of money to travel to Africa and go on a safari promising the opportunity to shoot exotic wild game like giraffes, lions, or elephants is ethically unacceptable. The killing of Cecil the lion, for example, caused outrage around the world. For some, what is objectionable is the idea of slaughtering any animal at all for any purpose. For others, it might be the exploitative nature of Westerners spending large sums of cash to shoot African animals, or the fact that the black market trade of goods like elephant tusks is made worse by the practice of safari hunting. Addressing these issues can be tricky: Germany has recently threatened to place greater limits of trophy hunting due to poaching concerns; Botswana, meanwhile, has threatened to send 20,000 elephants to Germany due to overpopulation of the species. Stories like this remind us how complex the ethical issues involved in animal tourism can be.

Tanzania comes in at 165th place in terms of nominal GDP per capita and Botswana comes in at 86th. These are developing nations where the average person makes relatively little money compared to the rest of the world. Despite this, the very rich can book photo or hunting safaris at five-star hotels like the Four Seasons Serengeti Safari Lodge for thousands of dollars a night. If one wishes to hunt wild game, they can select from an established menu where the price of hunting each animal is clearly listed. Hunting a baboon might cost $100 while hunting a leopard will cost $4500. An African elephant with at least one tusk over 30kg will cost $20,000 to kill.

It’s not surprising why a system like this would strike one as unethical. For starters, there is the basic act of hunting animals for sport, which many consider to be inherently wrong. Since reasonable alternatives to hunting exist, inflicting unnecessary harm and suffering on animals who are living their natural lives is morally wrong. But the consequences are even bigger than this. Trophy hunting not only wrongs the individual organism, but it can affect entire communities of animals if they work on packs or groups. The practice can also destabilize migration and hibernation practices, upsetting the balance of various ecosystems.

In addition to ethical views such as utilitarianism or the capabilities approach which might stress the ethical importance of minimizing harm or having a meaningful relationship with the animal world, there is also the additional concern that certain animals like elephants seem to have a heightened level of consciousness, including the ability to recognize themselves. This suggests that hunting certain kinds of animals may constitute an additional form of wrongdoing.

There is also the fact that these safaris feel like just another case of Western exploitation of African economies. Having outsiders spend small fortunes to hunt (or even photograph) the local fauna while residents survive on a fraction of what is spent each day. If this is one of the few ways to bring investment into the local economy, it would appear African countries don’t have much of a choice about tolerating the practice.

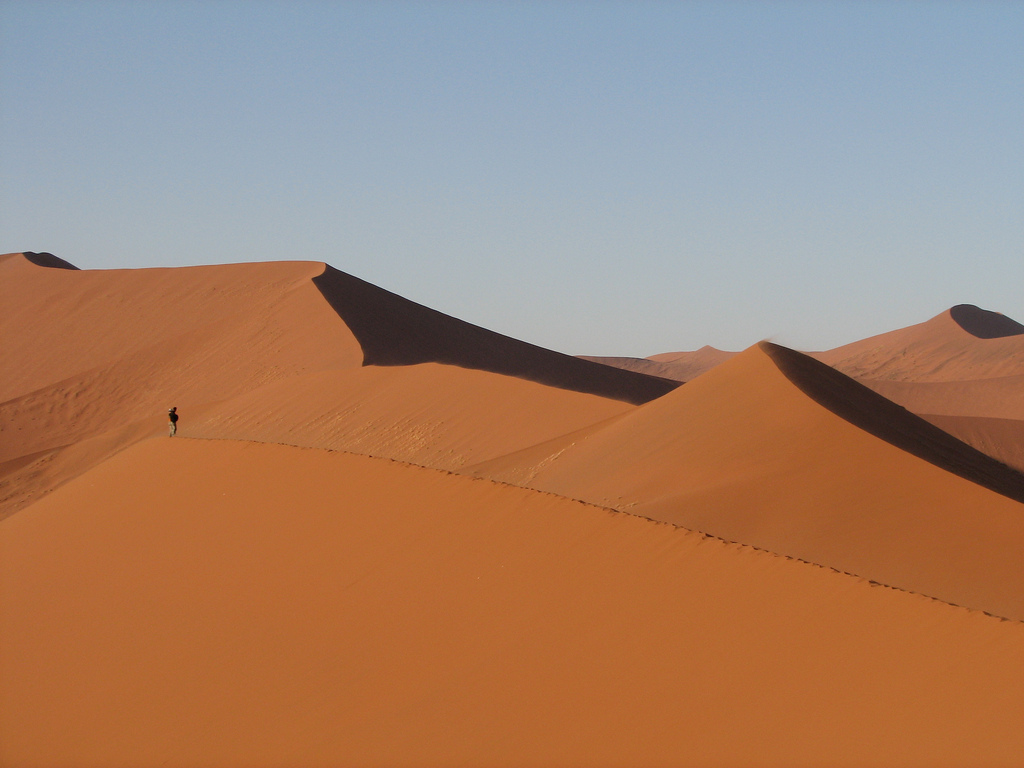

On the other hand, defenders of hunting and photo safaris will argue that conservation of the African savanna requires great sums of money. The national parks and hunting reserves that have been saved from agricultural development creates an opportunity cost for local development that must be offset. If these animals are left alone, they may be more inclined to wander into local villages and cause damage. This possibility makes it difficult for locals to want to support conservation.

Additionally, the high value of black market goods such as ivory presents a significant incentive to engage in poaching. Failing to regulate this practice threatens grave consequences. Given the incentives, we should anticipate a tragedy of the commons scenario where poachers and developers acting only in their self-interest will ruin the local habitats and endanger more animal species.

To prevent outcomes like this, African governments allow trophy hunting and photo safaris because the revenue from these businesses can be used to pay for conservation efforts. According to one study published in the journal Global Ecology and Conservation, trophy hunting contributes more than $341 million to the South African economy and supports more than 17,000 jobs. Safari operations help support anti-poaching patrols, provide employment for locals, and build infrastructure for rural economies.

But defenders of game hunting argue that “African wildlife conservation can only be justified if that ground generates enough revenue to support local communities whilst maintaining a healthy ecosystem.” Hunting and photo safaris then must accomplish a great many tasks. Ultimately, the hope is that we might incentivize active conservation by giving these animals a very different kind value. Killing some animals thus becomes a means to save many more.

Still, many consider the defense of safari hunting on the grounds that it provides the resources required for conservation to be questionable. A separate study conducted for Humane Society International has found that the economic benefits of trophy hunting are sometimes overstated. They found, for example, that trophy hunting only contributes closer to $132 million per year. There are also concerns that studies do not properly consider the difference in the economic benefits of not engaging in trophy hunting and engaging in it when it comes to comparing tourism projections.

Even if we consider only photo safaris, there are risks that creating a market to support conservation has led to a perverse incentive. The money to be made from tourism often proves too enticing, leading to greater development of infrastructure to support more and more tourists instead of greater conservation efforts. Further, There are concerns that tourists coming to Africa to see pristine wilderness are destroying it by their very actions. Even without hunting, wildebeests are declining and migration patterns and behavior of wild animals are changing as they become more and more accustomed to photo tourists.

Easy answers to these growing problems are nowhere in sight. While we may have moral objections to these safaris, banning the practice could very well lead to worse outcomes for the local animal populations. It’s far from clear what course of action will produce the greatest benefits over the long term.