It’s nearing the end of the semester, and many students will be waiting on the edge of their seats to receive their final grades. For those who seek higher education, their GPA will matter for their applications to med school, law school, and other graduate schools. This numerical representation of a student’s academic achievement allows institutions, like universities and medical schools, to have some objective measure by which to discriminate between applicants. And perceptive students can figure out ways to maximize their GPA.

A numerical representation of academic performance is a good thing, right? It is both legible and achievable. However, if we look at contemporary philosopher C. Thi Nguyen’s work on value capture, the answer might not be so clear. According to Nguyen, “value capture occurs when: 1. Our values are, at first, rich and subtle. 2. We encounter simplified (often quantified) versions of those values. 3. Those simplified versions take the place of our richer values in our reasoning and motivation. 4. Our lives get worse.”

To see how this process works, take Nguyen’s example of the Fitbit. Say that I’m trying to start off the year healthier and increase my exercise. My thoughtful mother buys me a Fitbit so that I can track my steps and try to meet a goal of 10,000 steps a day. After a while, I find myself motivated to get 10,000 steps in a day, but that motivation has now replaced my earlier motivation to be healthier and get more exercise. I may be walking more, but I might be neglecting other forms of movement and a more holistic practice of promoting health to meet the clear and concrete goal of meeting my step count. Depending on how obsessed I am with the 10,000 steps number, my life has probably gotten worse. This is the process of value capture.

Are grades subject to value capture? Let’s start with the first step. What are the prior values we are trying to measure with grades? At the broadest level, it seems that grades are meant to capture how well a student is performing given the standards of the class, which are subsequently determined by the standards of the discipline. Given the complexity of any given subject and the many ways that subject could be broken down into a class, it’s very difficult to give a clear and easy explanation of what any given grade is trying to capture. And the same grade could mean different things — two students could be performing equally well in a class but each have different strengths. The values that grading tries to capture are evidently rich and subtle values. Step 1 is complete.

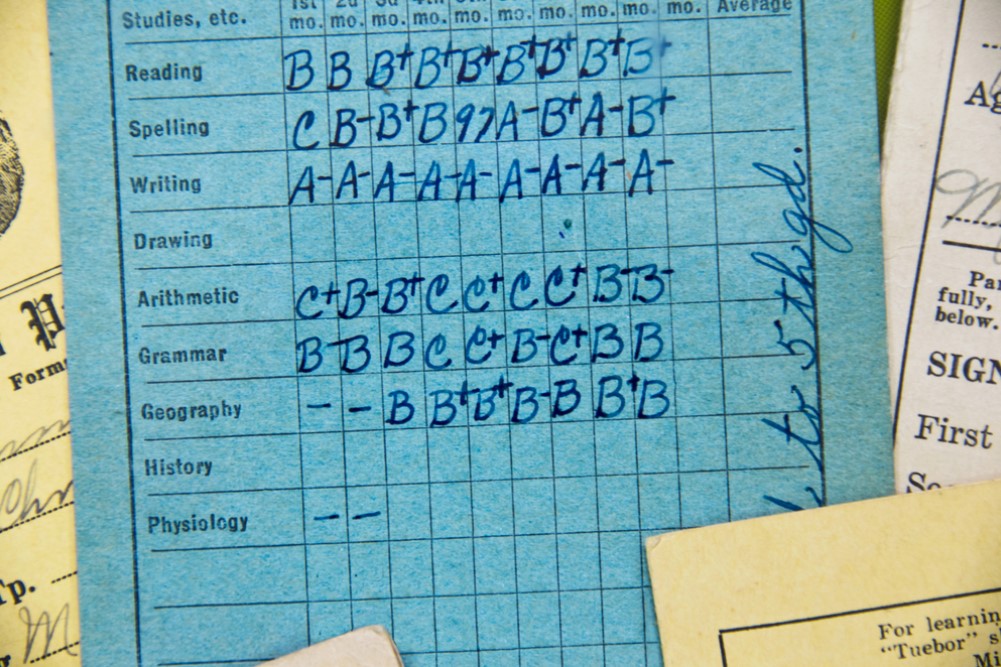

Do grades represent simpler (and sometimes quantified) versions of these rich values? Yes. Grades capture student performance into a number that can be bureaucratically sorted through at an institutional level. This has certain benefits — a law school can quickly do an initial sift through applicants to ensure that they have a sufficiently high GPA and LSAT score. But it also has its drawbacks. It doesn’t capture, for instance, that a slightly lower grade in a very hard class represents better student performance than a higher grade in an easier class. Given the standardized format of grades, a student’s scores may also do a poor job at representing personal growth and achievement that may vary based on the social and educational starting points of different students. Steps 1 and 2 are complete.

What about step 3? Do grades take the place of our richer values in our reasoning and motivation? It seems that often they do. This is in part because of external motivations, such as the importance of grades for employment or getting into a certain program. But it is also in part because of the ways in which we tend to start valuing the grade for its own sake. Think about, for instance, the parent who wants their child to succeed. Instead of focusing on the actual progress their child is making given the challenges their classes present, that parent can easily be seduced by the clarity and seeming objectivity of their child’s grades. The goalposts can quickly shift from “being a good student” to “making good grades.”

This shift can happen for students as well. Grades are often the most tangible feedback they get from their instructors, even though they may sometimes receive qualitative assessments. Grades may feel like a more real and concrete measure of academic performance, especially because they are the record that remains after the course. Students who start off valuing education may easily get sucked into primarily working to maximize their grades rather than to maximize their learning. It is worth noting that Nguyen himself thinks that this motivational shift happens with grades, noting that “students go to school for the sake of gaining knowledge, and come out focused on maximizing their GPA.” Steps 1, 2, and 3 are all complete.

What about step 4? Do grades make our lives worse? This is a hard question to answer, as it’s an empirical question that depends on a myriad of different personal experiences. In my own experience, focusing on getting a higher grade has often interfered with my ability to learn in a course. Instead of diving into the material itself, I often got stuck at the level of trying to figure out how to make sure that I got that A. In harder courses, this would make me very stressed as I worked exceptionally hard to meet the requirements. In easier courses, this would mean that I often slacked off and did not perform as well as I could have, since it was an easy A. And, as much as I tried to shake the motivational pull of grades, it was always there. Grades made my educational experience worse.

What should we do with this problem? Given the potential for value capture, grades are a powerful tool, and teachers should be careful to create an assessment structure that more closely incentivizes an engagement with the rich, pluralistic values that students should come to appreciate. This is a difficult task, as often those values cannot be easily translated into a grading system that is legible to the institution (and to other people across institutions). Because grades provide an easy way to communicate information, it’s unlikely that getting rid of them would make things better, at least in the short-term.

One solution might be to retain the current numerical/letter grade assignments but to add on a short paragraph qualitatively assessing the student’s performance throughout the course. This could be fraught for a number of reasons (including implicit bias, the bureaucratic logistics of tracking of such information, and the additional work for teachers), but that extra information would help to contextualize the numbers on the page and provide a richer understanding of a student’s performance, both for that student and for those assessing the student as an applicant. This solution is far from perfect, but it might provide one step towards recapturing our motivation to track the rich values we started with.