Recently China has taken steps towards preserving exotic wildlife that have become endangered species. In 2017, China closed its market of ivory to protect African elephants and stop the illegal wildlife trade. This step commenced “China’s reputation as a leader of conservation” according to a Tiger Campaign Leader at the Environmental Investigation Agency. However, as of October 29, 2018, the state Council, under Premier Li Kequiang, made a public decision to permit the controlled sale of rhino horns and tiger bones for research or traditional medicine. In doing so, they ended the 25-year-old ban of these products. The announcement discloses that “Rhino horns and tiger bones used in medical research or in healing can only be obtained from farmed rhinos and tigers,” restricting the open trade to only legal farms and not risking the remaining wild endangered populations. Conservationists, such as the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF), consider this a major hindrance for the exotic animal populations.

Conservationists argue that this new law could lead to a surge of illegal wildlife hunting and trading which would further threaten the already vulnerable animal population. This legal market gives the illegal transactions a place to hide. “The resumption of a legal market for these products is an enormous setback to efforts to protect tigers and rhinos in the wild,” says Margaret Kinnaird, of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Selling legal rhino horns and tiger bones signals that it is ethically okay to buy the products. The price of a rhino horn has peaked at $65,000 per kg, which is already more valuable than gold and elephant ivory. Today, at least three rhinos die per day because of hunting for their horns. It is expected that as the demand rises for this trade, the threatened population will continue to decline. Speaking on behalf of WWF, Leigh Henry, Director of Wildlife Policy, “urgently calls on China to maintain the ban on tiger bone and rhino horn trade which has been so critical in conserving these iconic species. This should be expanded to cover trade in all tiger parts and products.” Conservationists clearly argue the value of protecting the wildlife, such as tigers and rhinos.

An important aspect of the new law is that the rhino horns and tiger bones can only come from farms. This approach has also been promoted by South Africa and other African governments that have been encouraging private farming of exotic animals. The World Wildlife Fund says there are fewer than 4,000 tigers living in the wild, but there are some 6,000 captive tigers, farmed in about 200 government-sanctioned locations across China. Farms that house these wild populations could be protecting them from extinction. To support this, Lu Kang, the foreign ministry spokesman, said that China’s 1993 ban on the products did not take into account the “reasonable needs of reality,” adding that China has improved its “law enforcement mechanism.”

To enforce this new law, it has been found that rhino horns are relatively easy to microchip and can have samples taken for DNA analysis. It is this kind of DNA analysis that conservationists argue would be necessary to regulate the illegal trade from the legal farms. Although it’s possible that the horn can be traced back to an individual animal, it is not clear yet how to verify a powdered rhino horn, a product that would be used for medicinal purposes, which may come from more than one animal. After all, the purpose of the law was to preserve the culture of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), which requires the usage of tiger and rhino products.

Recently, World Health Organization (WHO) took a stance to support TCM along with other traditional medicine practices as a step towards long term universal health care. Traditional treatments are less costly and more accessible than Western medicine for some countries. This would extend the scope of medicinal practices to include a larger amount of people. According to the director-general of WHO, there is a cost advantage of supporting TCM because treatments are more pioneered towards lifestyle changes, herbal remedies, and reducing stress levels. However, Western scientists are concerned that TCM practices are not supported by clinical trials and therefore could be dangerous. TCM treatments are based on Theories of Qi, which means vital energy to help the body maintain health. Common treatments include acupuncture or herbal remedies. The rhino and tiger are both animals that have connections to virility and strength, providing help to patients with back pain, arthritis, and even hangovers.

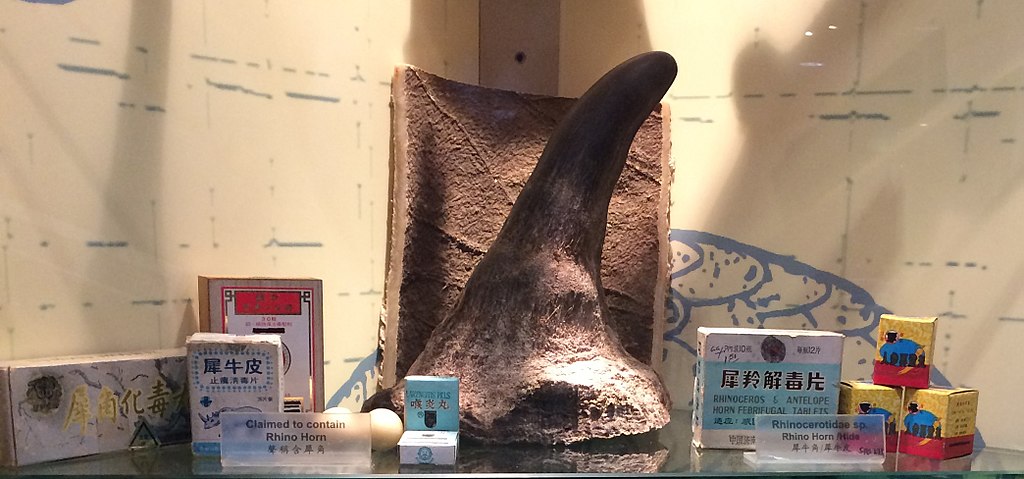

Part of the new law states that the purpose behind it was to allow research or usage for traditional medicine. Rhino horns are made from the protein keratin, which is advertised to help treat everything from cancer to gout. However, there is a lack of Western medicinal evidence that proves this. A rare study from 1990 found that rhino horns can lower fevers in rodents, very similar to aspirin or acetaminophen. Tiger bones in medicinal use are crushed and made into a paste that can treat rheumatism and back pain. Yet again, there is a lack of scientific Western studies that support this claim.

Western scientists have spent millions of dollars on trials of TCM with little success. Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine surveyed 70 systematic reviews measuring the effectiveness of traditional medicine practices, like acupuncture. The studies couldn’t reach a solid conclusion that supported positive effectiveness. Going along with Western medicine viewpoints, one would argue that the intention behind China’s new policy is not supported with evidence that the rhino horns and tiger bones are an effective form of medicine. Overall, there are ethical ramifications of this issue that lie beyond the scope of preserving wildlife. The ethical arguments extend to differences between western and traditional medicinal practices and the means to be able to practice both.