In late July, the Florida Department of Education announced that it would issue five-year vouchers to veterans which would allow them to work as teachers in K-12 schools without the requirements of a degree, a teaching certificate, or any experience teaching. The policy was adopted in response to two crises: a significant shortage of teachers with the beginning of the school year rapidly approaching, and a long-standing problem of failing to secure employment for veterans after they have finished their service.

The United States has an abysmal record when it comes to making sure that veterans are well cared for when they finish serving; the homelessness rate among veterans has historically been quite high. Florida has enacted initiatives to combat veteran unemployment and homelessness which have had some significant success.

The question, then, is not whether Florida should do everything they can to employ veterans and their families, but whether employing them as K-12 teachers is something that Florida can defensibly do.

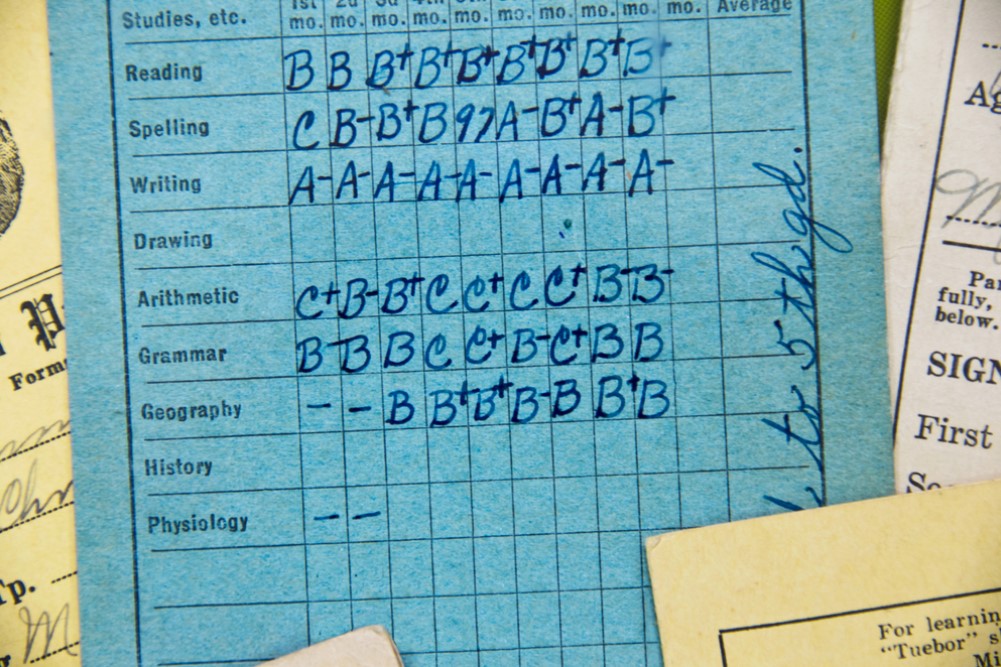

The most significant concern about this policy is that it lowers the bar for what counts as quality education in the state of Florida. The role of an educator is an academic position, and it requires specialized knowledge. Not only does it require knowledge in the specific field in which the educator will teach, it also requires training in effective pedagogy. People who are trained in education are trained in methods that are the most effective in helping students to learn. They also receive training on important elements of the job such as grading, learning management systems, and responding to special challenges that students might face. The education of our young people is a significant moral responsibility; their futures are, in many ways, largely determined by the educational opportunities to which they have access early in their development. What’s more, the success of our democratic institutions relies on well-educated citizens who are strong critical thinkers and can reason well about how society should be structured.

Given the gravity of the responsibility, it is important that we put these tasks in the hands of people with the proper training. To do otherwise is to discount the value of education and to continue a nationwide trend of anti-intellectualism and de-valuing education.

One reason for the existing teacher shortage may be the way they treat their teachers; Florida ranks 49th in the nation when it comes to teacher salaries. In the 2019-2020 school year, the average teacher salary was $49,102. DeSantis recently approved $800 million to raise teacher salaries, but this will not be a significant increase per teacher. These low salaries are compensation for a job that requires substantial amounts of work off the clock; teachers spend much of their time at home grading assignments and preparing lessons.

This is taking place in a state that hasn’t exactly earned a reputation for supporting teachers. When school went virtual during the pandemic, teachers were often blamed for what some parents deemed to be the lower quality or engagement level of online education. When education moved back to the classroom (which it did very early on in Florida), teachers were accused of stunting their students’ social development by enforcing mask mandates and social distancing requirements. At the height of the pandemic, teachers were vilified while being offered very little in the way of health protections.

All of this is also taking place in an area of the country that has made national headlines for what many view to be its authoritarian nationalistic measures when it comes to controlling curriculum. As the Black Lives Matter movement motivated many educators to think about the ways in which they discuss race in the classroom, in 2021, Florida became one of the first states to ban teaching critical race theory in K-12 classrooms. Critical Race Theory is a legal theory made popular in law schools in the 1970s that examines the ways in which racism has impacted law in the United States and beyond. Needless to say, Critical Race Theory was never being taught in K-12 schools, it is advanced material.

To the extent that there is content to object to, it seems that the objection is really to education that portrays racism as a substantial, even defining aspect of the American narrative, central to our history and enduring today in a systemic form.

Politicians and pundits have stirred up considerable fear that students who are exposed to such course material will develop into self-loathing people who resent their country and are no longer patriots. Those who favor anti-critical race theory legislation argue that history lessons should portray the founders of this country as brilliant rebels who fought for and won our freedom against British rule. Dissenting voices point out that many of them were also slave owners who perpetrated a genocide against Native Americans and that we continue policies of marginalization and oppression toward these populations to this day. These are facts about our history that are far too seldom acknowledged in the K-12 classroom. Educators who feel that justice requires more in-depth discussion of our history when it comes to race feel targeted and threatened by recent legislation and political maneuvering.

In addition to legislation pertaining to race, Florida has also recently passed legislation that is referred to throughout the country as the “Don’t Say Gay Bill,” an aggressive piece of legislation with many components that impact LGBTQ children and their parents. First, the law prohibits instruction on the topic of sexual orientation or gender identity in grades K-3. More generally, it prohibits discussion of topics that are not “age or developmentally appropriate.” The vagueness in this language is viewed by many teachers as a threat to their job security. LGBTQ people exist and questions about them come up regularly in conversation, especially with young, curious people. Some teachers are members of the LGBTQ community, many of whom feel that they can’t answer basic questions about themselves because doing so might put their livelihood at risk. It is reasonable to view policies like these as an affront to their basic dignity and as a relic of an earlier time when LGBTQ people in professions were viewed as dangerous threats.

The legislation also requires transgender students to fill out a “Gender Support Plan” should they express a desire to be referred to by a preferred pronoun. This plan cannot be completed without the consent and involvement from the student’s parents. Similarly, the law requires students seeking mental health services at the school to do so only with the consent of their parents unless the school has reason to believe that notifying the parents will “subject the student to abuse, abandonment or neglect.”

The legislation in its entirety makes it fairly clear that the state of Florida does not consider lack of support for a student’s sexual orientation or gender identity to be abuse, even though such treatment increases rates of depression, anxiety, homelessness, and suicide.

Sadly, sometimes it is parental treatment which creates a need for counseling and support services. Teachers care deeply about their students, and many want to help their LGBTQ students access the services they need in order to protect their mental health and physical well-being. This law creates a chilling effect on the support teachers feel safe offering their at-risk students.

Populating classrooms with veterans compounds these issues. Veterans often exhibit high levels of patriotism and nationalism. It is common for people who do not have degrees beyond high school to be unfamiliar with sociological information about and history of groups to which they do not belong. This is not innate knowledge, after all. The United States has a fraught history when it comes to LGBTQ issues and the military, where gay soldiers were not able to openly serve until 2011 and Transgender individuals were banned from enlisting by the Trump administration (that ban was reversed by the Biden administration). Placing people who were once in the armed forces with no training in education into teaching roles seems to many as doubling down on discriminatory educational policies by placing people who may not be sympathetic to racial challenges or LGBTQ issues into the classroom. Of course, not all veterans have the same political affiliation, but hiring from this pool makes similar ideological commitments more likely.

All of this makes the classroom a very unstable environment for qualified teachers in Florida. There is little wonder that the state is not currently attracting lots of people with the proper credentials to fill the gaps. What’s more, to many, all of these moves seem politically calculated — poorly educated voters are easier to manipulate and creating “us” and “them” classes, otherizing, and fear mongering are classic tools in the playbook of demagogues. These people are quick to point out that Florida Governor Ron DeSantis is viewed as virtually certain to run for President in 2024 with the hopes of appealing to the same demographic that supported former President Trump.