Editor’s note: This article contains use of a vulgarity.

This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

At around this time last year a Google spreadsheet titled “Shitty Media Men” began being shared by a group of women who worked in various positions involving the media. The document was intended to be a place where women could anonymously make reports about inappropriate conduct of men who they worked with, ranging from unsolicited advances or generally creepy behavior, all the way to accusations of sexual assault and rape. Moira Donegan, the creator of the list, explained her intention at The Cut as “an attempt at solving what has seemed like an intractable problem: how women can protect ourselves from sexual harassment and assault.” As Donegan goes on to note, “informal alliances that pass on open secrets and warn women” called “whisper networks” have been common for a long time. In creating a more widely accessible document, however, Donegan wanted to provide access to this information to a much wider audience, allowing those who might not have been part of a whisper network to gain information and share their experiences.

Once the existence of the list became public knowledge, however, it started to receive backlash. Some worried about the claims on the list being unsubstantiated, and that the men accused on the list were unable to respond to the accusations made therein. And there were repercussions for being named on the list, with some men having investigations performed by their employers into their conduct, and others being fired. The prominent worry, then, was that the accusations made on the list could be false, and the consequence of a false accusation is the punishment of an innocent man.

Recently, one man named on the list, Stephen Elliott, filed lawsuit against Donegan for damages, to the tune of $1.5 million. On the “Shitty Media Men” list Elliott was accused of sexual harassment and rape, amongst other things. In an extensive reply, Elliott has denied all accusations, and claims that as a result of being accused he has suffered in the form of reduced book sales, being cut off from professional contacts, and suffering psychologically.

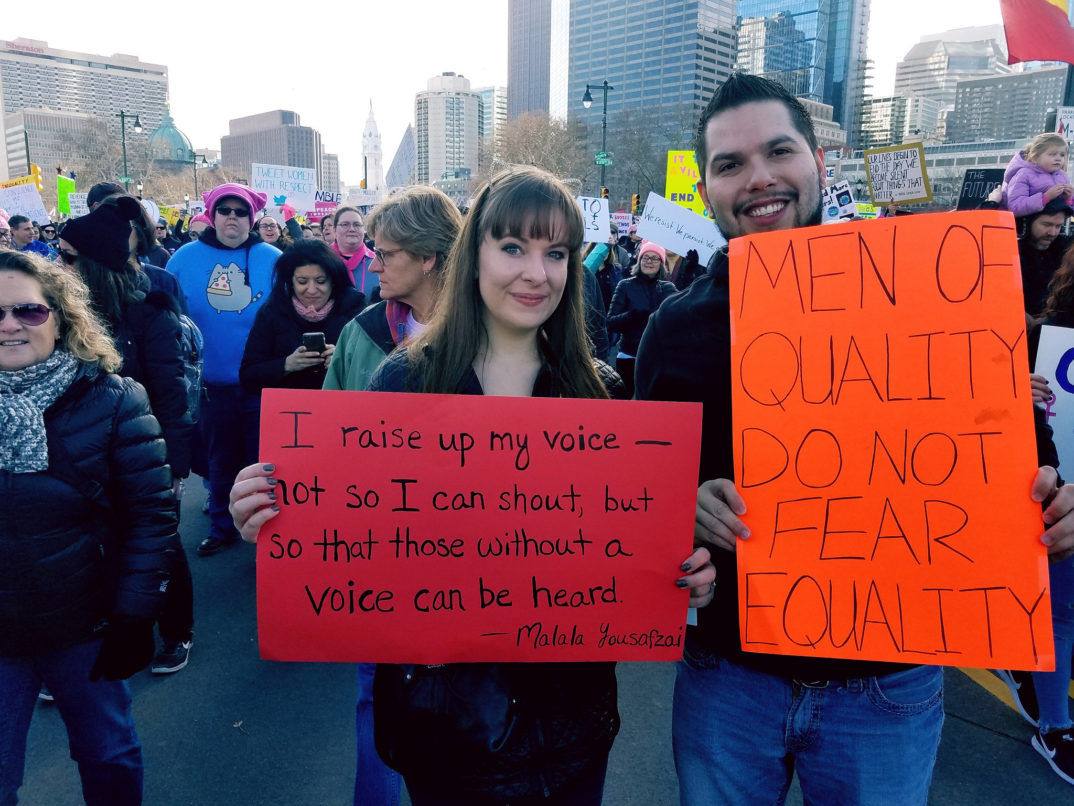

The fear that innocent men will suffer from being falsely accused is becoming increasingly common in the wake of the #metoo movement, as well as with what appears to be a very gradual shift towards taking women’s accusations of sexual assault seriously. For instance, the response to the recent swearing in of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court has been divided between those who believed that the testimony of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford ought to have been given much more consideration, and those who believed that to take the testimony of Dr. Ford seriously would be to risk derailing a man’s career on the basis of accusations that they thought did not meet the proper standards of proof. Recently, Donald Trump expressed that it was “a scary time” for men, even going so far as to act out a one-man show in which a falsely accused son explained melodramatically to his tearful mother why he had lost his job.

The ethical worry surrounding things like the “Shitty Media Men” list, then, is that it potentially puts innocent men at risk: merely being named on the list has potential consequences, and since anyone can make accusations anonymously, the worry is that not only will such false accusations be possible, but prevalent. Of course, the existence of such lists also have the potential to bring about a lot of benefits. As Donegan explains, it is often the case that “for someone looking to report an incident or to make habitual behavior stop, all the available options are bad ones”; notably, that “police are notoriously inept at handing sexual-assault cases” and that within a corporate environment, “human-resource departments…are tasked not with protecting employees but with shielding the company from liability.” The benefits of such lists, then, are that women can help other women avoid potential harm, and that women can have an alternative option to make a report. While those like Elliott claim psychological harms from being named on the list, the existence of such a list could also prevent a significant amount of psychological harm suffered by women whose reports are not taken seriously, or who feel that they really have no other way to name their accusers.

One way that we can evaluate whether it’s a good or bad thing to have a “Shitty Media Men” list is by weighing the potential goods versus the potential harms that could come about as a result of its existence. As many commentators have noted, the fear of men being falsely accused tends to be exaggerated: although it is difficult to get an exact idea of how common false accusations are, various sources have put the rate at around 5%, although that number might be as low as 2% or as high as 10%, at least in America. At the same time, while it is again very difficult to get a sense of the numbers, there is good reason to think that sexual assault is generally underreported. It seems likely that providing additional avenues for reporting would then help with the problem of underreporting, which would be a significant benefit to many women. If these lists result in significantly more potential benefits than potential harms, then, there is reason to think their existence really is a good thing.

Calculating costs and benefits in this way, however, may not seem to be very satisfying. Indeed, we might think it would be better if the existing options that women had to report assault weren’t so bad, perhaps if police, human resource departments, and political leaders were better trained. And it may seem callous to suggest that men who are falsely accused are an unfortunate but necessary collateral damage. That being said, given the obstacles that women continue to face in having their reports taken seriously, the continued existence of such lists seems inevitable. In considering whether this is a good or bad thing, we need to keep in mind both the relative paucity of false accusations, and the benefits that the existence of the “Shitty Media Men” list could bring.