This is the second in a series on American History and the Ethics of Memory. This post originally appeared on September 15, 2015.

Warner Madison doesn’t trust the police. He thinks they view all black people with suspicion, harass them on the streets, and arrest them without cause. When police accost his children on their way to school, he can barely contain his anger. He fires off a letter protesting what he calls “one of the most obnoxious and foul and mean” things he has ever witnessed. But he possesses little hope that police treatment of African Americans in his city will change.

What does Warner Madison think of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, Samuel DuBose? There’s no telling. He’s been dead for probably more than a century. Warner Madison’s outrage about race and policing came to a head just after the Civil War, in 1865, when he was a 31-year-old barber living in Memphis, Tennessee.

Memphis isn’t among recent flashpoints—Ferguson, North Charleston, Baltimore—nor does it crop up among placenames associated with racial violence of decades past—South Central, Crown Heights, Watts. In collective memory of American history, Memphis figures as the scene of a lot of great music and the assassination of Martin Luther King. Yet the Memphis of Warner Madison’s time is an essential, though largely forgotten, part of understanding race and policing in America.

A recent New York Times article suggests Americans are living through “a purge moment” in their relationship to history. Especially since the June shooting at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, icons of slavery and the Confederate States of America have been challenged and, in many cases, removed: the Confederate battle flag from the South Carolina statehouse grounds and, most recently, a statue of Jefferson Davis from the University of Texas at Austin’s Main Mall. At Yale University, students are now debating whether to rename Calhoun College, which honors a Yale alumnus who is best known as the antebellum South’s most ardent defender of slavery.

Skeptics are concerned about “whitewashing” the past or hiding important if controversial aspects of our history in “a moral skeleton closet.” (At the extreme end, one can find online commenters likening such reconsiderations to ISIS’s destruction of pre-Islamic antiquities in Syria.) But there’s little harm and often much good in collective soul-searching, as among the students at Yale, about how best to remember a community’s past and express its shared values—whatever decision that community may finally come to about its memorials. And, as I argued here previously, memory is a scarce resource. Figures like Jefferson Davis and John C. Calhoun shouldn’t be forgotten, but their public memorialization, in statues, street names, and the like, keeps them before our eyes to the exclusion of things we could be remembering instead—things we might find more useful for understanding the world around us.

Take Memphis in the 1860s. A southern city that fell to Union forces only about a year into the Civil War, in June 1862, it became a testing ground for the new order that would follow the destruction of slavery. As word spread across the countryside that the reputed forces of freedom had taken Memphis, African Americans flocked to the city. By the end of the war, Memphis’s black population had grown from 3,000 to 20,000, and surrounding plantations were proportionately emptied—to the dismay of cotton planters who needed laborers in their fields.

White authorities forcibly moved former slaves back onto the plantations. How? Using newly invented laws against “vagrancy.” Memphis blacks who could not prove gainful employment in the city were deemed vagrants, and vagrants were subject to arrest and impressment into the agricultural labor force.

Vagrancy had existed as a word and a phenomenon for centuries. In the post-Civil War South, it became a crime. Vagrancy laws were mainstays of southern states’ “black codes” during the late nineteenth century, because they helped white supremacists restore a social order that resembled slavery. Black men without jobs were guilty of the crime of vagrancy simply by going outside and walking down the street. Once arrested and imprisoned, they could be put on chain gangs—and white southerners could once again exploit their unpaid labor.

It’s not surprising that former Confederates were responsible for criminalizing black unemployment. But so was the Freedmen’s Bureau—the federal agency expressly charged by Congress and Abraham Lincoln with assisting former slaves in their transition to freedom. The bureau’s Memphis superintendent wrote in 1865 that the city had a “surplus population of at least six thousand colored persons [who] are lazy, worthless vagrants” and authorized patrols that were arresting black Memphians indiscriminately.

When some of the leading black citizens of Memphis had seen enough of this—men taken away to plantations at the points of bayonets, children stopped on their way to school and challenged to prove they weren’t “vagrants”—they called on the most literate people among them, including Warner Madison, to compose petitions to high-ranking federal officials. Paramount among their grievances was the harassment of “Children going to School With there arms full of Book[s].” To the African American community, freedom meant access to education. But to whites—even the very officials responsible for protecting black rights—freedom meant that African Americans needed to get to work or be policed.

Clinton Fisk, a Union general during the war, now oversaw Freedmen’s Bureau operations in all of Tennessee and Kentucky. He replied politely to the letters he received, but he never credited or even mentioned the reports of abuse Warner Madison and his compatriots provided. He asked his subordinate in Memphis to investigate, and the unbothered report came back: “I can find no evidence whatever that School children, with Books in their hands have been arrested, except in two or three cases.” Even Clinton Fisk—an abolitionist who so strongly advocated African American education that Fisk University bears his name—failed to affirm that having a book kept a person from being vagrant.

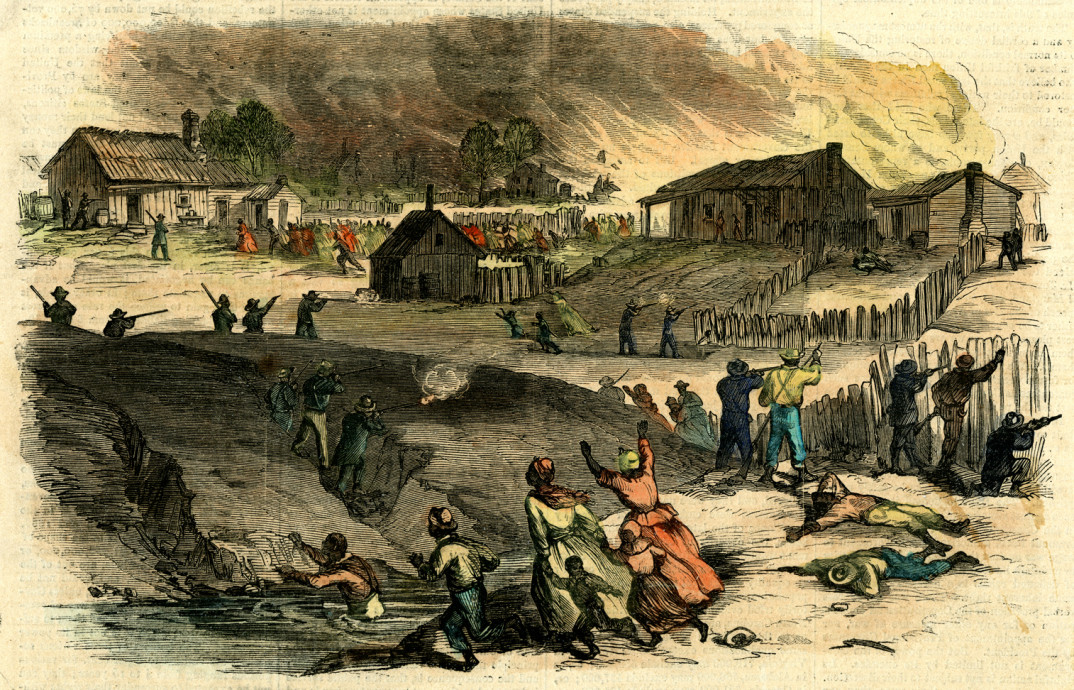

This period of conflict culminated in the Memphis riots of 1866—an episode that ought to be infamous (and is the subject of a few good books) but is generally absent from public consciousness. White Memphians initially assumed the “riots” were a black protest that turned violent, but what actually occurred in Memphis on the first days of May in 1866 was a massacre of black men, women, and children by white mobs, among whom were many police officers.

In failing to remember 1860s Memphis—failing even to know the name of someone like Warner Madison, after whom no highways or elementary schools are named—we fail to remember that the federal government once made it the special province of law enforcement agents to accost African Americans in public places. Without remembering that, we cannot apprehend the complexity and durability of the problems underlying current events.

What we now call “racial profiling,” and even the appallingly frequent uses of lethal force against black citizens, may result less from the implicit bias of police officers than from a historical legacy. Abiding modes of law enforcement and criminal justice, brought to us by nineteenth-century white Americans’ anxieties about the abolition of slavery, were designed to treat black people walking freely on city streets—unless they were being economically productive in ways white people approved—as social threats.

Racism may be only a partial explanation. Some of the people who were arresting “vagrants” in Memphis were African American—they were soldiers in the U.S. Army acting under Freedmen’s Bureau orders—and so are three of the six Baltimore police officers charged with the death of Freddie Gray. Blame may rest, too, with habits of mind upon which few people even frown—like taking gainful employment as a measure of human worth (a pernicious corollary of the belief that markets possess wisdom), or presuming that someone must be up to no good if he has (in Chuck Berry’s words) no particular place to go.