Nursing is no longer federally classified as a professional degree. When news broke in November, the American Nurses Association condemned the action, arguing the move drains funding for pre-service nurses, “undermining efforts to grow and sustain the nursing workforce.” In response, The Department of Education argued that this is “not a value judgment” but, rather, “distinguish[es] among programs that qualify for higher loan limits.” Still, the declassification itself seems to reflect a valuation and, in turn, risks social devaluation of nursing and similar professions.

This demotion comes alongside an overwhelming underwhelm of support for other social services, including budget slashes for public schooling and behavioral healthcare. The laborers behind these so-called “helping,” “care,” or “service” professions fill interpersonal roles in direct aid to others’ well-being. The category includes nurses and emergency responders, school counselors and teachers, and psychologists and social workers.

In addition to their licensure requirements, care professions are also characterized, in the United States, by a low amount of support. This creates a disillusioning disparity: high standards for hire with low standards for working conditions. What might this gap — and its persistence — say about our perceptions of the helping professions?

First, let’s consider the prerequisites for working as a service professional.

Social workers, for instance, require a master’s and, just like registered nurses, must pass a licensure exam after completing supervised clinical experience. Similarly, the road initial teaching licensure requires a bachelor’s in the teacher’s content area and an educator prep program (EPP): a yearlong apprenticeship, a teaching performance assessment (edTPA), and subject exams. New York teachers must earn a master’s degree within their first five years.

In other words, you can’t just walk into a school or hospital and be eligible for hire.

At least, that’s in most cases. One exception is found in Florida’s response to its teacher shortage: a United States veteran with four years of military service may obtain a teaching certificate without a bachelor’s degree or EPP. This specialization deviation has been met with alarm, implying an intuition that teachers should engage in specialized training. Granted, a degree isn’t the only opportunity for learning, but removing its requirement speaks, at least generally, to lowered standards for content expertise. At the end of the day, you probably can’t teach AP Statistics effectively without understanding statistics yourself.

The necessity of training is further evidenced by the challenges baked into helping professionals’ jobs.

For instance, nurses facilitate care for patients and their loved ones. First responders, by definition, arrive at emergencies before anyone else. This means horrific, perhaps end-of-life, encounters are a possibility for any given shift. 1 in 3 first responders develop PTSD (compared to the general public’s 1 in 5 chance). Teachers, counselors, and social workers accommodate individual student learning needs while delivering developmentally appropriate curriculum. They are often the only non-parent adults with daily eyes on a child, emphasizing the gravity of their duties as mandated reporters of abuse and neglect.

But we’ve heard about these challenges. They’re expected, inherent in the jobs themselves.

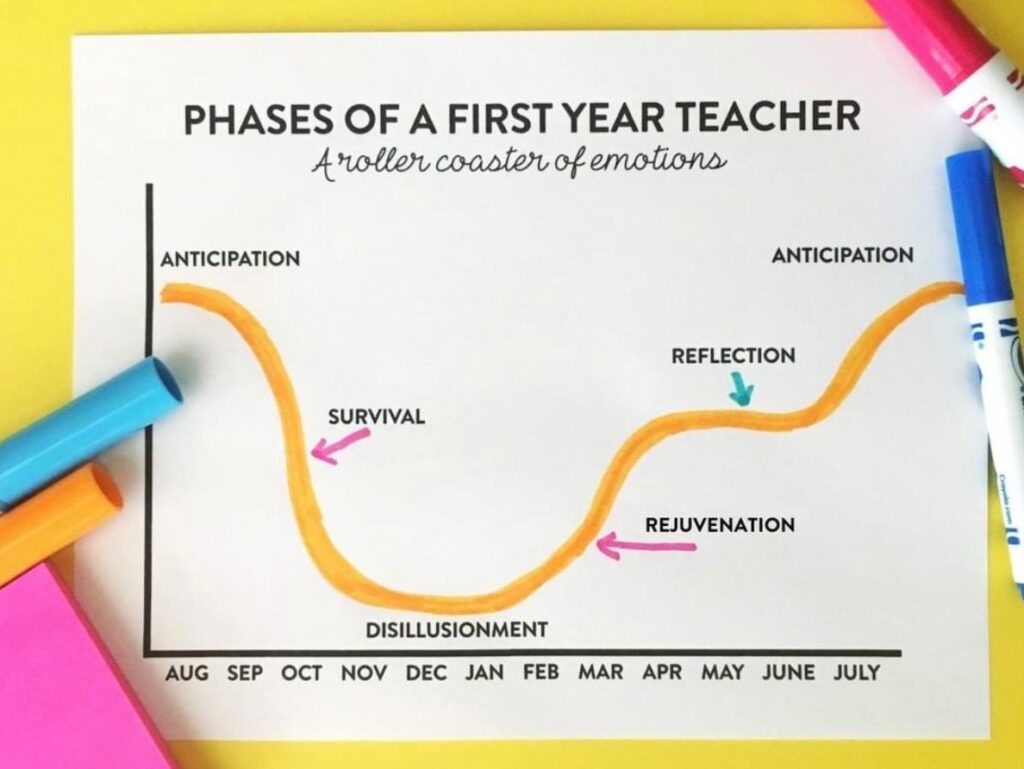

Instead, what deserves more airtime is the extent to which helping professionals are trained to expect structural failure: challenges emerging from inadequate support in, or as a result of, the professional environment. Unlike the challenges of caring for sick patients or teaching chattery kids, structural workplace obstacles could, theoretically, be eliminated. Consider, for instance, The First-Year Teaching Rollercoaster, a graph popularly shown to pre-service educators:

There’s something bizarre about telling someone to anticipate seasonal disillusionment. It’s off-putting to be able to do so with patterned years of data — and weirder if the listener is a professional-in-training in your field. In effect, this expectation-setting not only numbs newbies to workplace malfunction but also legitimizes routine floundering within it.

In analogy, suppose you are told your room will soon overheat. Given the warning, you are unsurprised to find moisture beading in your hairline or humidity fogging your view. But this warning, no matter how emphatically shared, will never cool the space or dry your sweat. All it does mean is that you’re likely to feel less justified in questioning the temperature.

But COVID-19 cracked these steaming fissures open. Structural failures — like increased workload, staff shortages, and elevated stress — and the subsequent burnout became unignorable.

Both before and eighteen months after the pandemic, The University of Pennsylvania collected well-being data on 70,000 licensed registered nurses in New York and Illinois. Results reveal that “64.9% of medical-surgical nurses reported insufficient staffing,” a number spiking to 75% mid-pandemic. Lack of confidence in hospital management moved from 69% to 78%. Most jarringly, higher patient-to-nurse ratios were found correlated with increases in likelihood of death.

These structural inadequacies promote further frustration by dominoing into devaluing workers’ professional specializations. For instance, in 2020, 39% of school counselors considered “being assigned inappropriate duties” a day-to-day challenge, as reported by The American School Counselors Association. Monitoring students in the morning and afternoon bus lines, as well as during class change and lunch duty, are essential tasks for a functioning school. However, these assignments total hours per week, all of which require emotional labor, none of which are expended on meeting students’ counseling needs.

This is not merely distracting or demoralizing. It is exploitative.

Trying to stretch a counselor, teacher, or a nurse thin wears down the very essence of the job itself. Conducting science class in a lab packed with nearly forty twelve-year-olds (a reality down the hallway from my classroom) is not the same as doing so in one half or third of its size. These conditions promote depersonalization, even if only by degrees. To be in a helping profession is, necessarily, to narrow one’s scope, to be interpersonal and slow and methodical and observant. You cannot mass-produce relationship.

This is why teachers, nurses, and first responders protest, quit, and eventually strike. They’re not enacting defiance merely in hopes of personal improvements. Rather, they’re speaking up because they can’t do their jobs.

It’s true strikes are disruptive. Those intended to be aided by these jobs are left underserved, leading some to suggest walkouts are unprofessional, selfish, or unethical.

However, it seems unlikely that a veteran paramedic who works twelve- or twenty-four-hour-long shifts and, literally, saves strangers’ lives merely “didn’t feel like working” after the pandemic. Perhaps, instead, a deep belief in the profession was her only tether to it until, eventually, the environment became inhospitable. When people who define themselves by the intrinsic value of their work threaten to walk away, there’s good reason to believe them to be canaries in a coal mine, sounding the alarm for help.

In October, over 31,000 Kaiser Permanente nurses, pharmacists, midwives, and rehab therapists went on five-day strike to protest insufficient staffing and salary’s lack of pace with inflation. In the same month, Cape Cod hospice nurses enacted a three-day strike in response to stalemated contract negotiations over “uncompetitive wages, recruitment challenges, and chronic turnover.” Disruption often becomes the only way to create change. In 1978, firefighters in Normal, Illinois walked off the job for fifty-six days in the longest firefighting strike in American history. One participant argues it set a new standard: “If we had not done that, and if we hadn’t been successful, there is no one in Normal that would have the benefits they have, the salary they have, the working conditions they have.”

Calling out a lack of support, in many cases, might enable these professions, and those who work in them, to persist in the long run.

However, collective bargaining is impermissible, at least nominally, for many helping professionals, who tend to be public employees and essential workers. Totaling roughly 730,000 in the recent government shutdown, these “excepted” federal workers must work regardless of appropriated funds and hope for back pay. Essential workers’ efforts are judged too integral to halt, which leaves them little ability to protest without objection or prompting substantial disorder.

For example, teacher strikes are unlawful in 37 states, by 2023 estimates. Nonetheless, Arizona, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and West Virginia all saw illegal walkouts in the heat of the 2018 Red for Ed wave. This series of strikes called out insufficient wages, benefits, and respect, emerging victorious in several dimensions. Though many of these efforts reaped victories, an estimated 1 in 8 teaching positions are unfilled or filled by inadequately certified teachers.

It’s hard to see what bars these systems from crumbling. Heart, maybe? Burnt-out nurses who celebrate patients’ birthdays while working, understaffed, on their own? A kindergarten teacher who, unpaid, unlocks his classrooms on a Saturday to fill empty shelves with books he bought?

When people take a job on the professed basis of duty, a decreased quality of its other attributes — salary, environment, autonomy — might be more willingly bared. There are nurses who “wanted to follow [their] mother’s steps and contribute, in some way, to improving people’s health and lives,” and there are educators who say,“Teaching students is wonderful. It is all the OTHER that is exhausting.” Until structural reinforcements come along, the helping systems will continue to rely on those in it nearly entirely out of love for who they serve.

Patterned lack of support for service professionals communicates, in many ways, that they are less deserving of quality working conditions because they chose their careers out of goodwill.

But is a person less deserving of respect merely because they are willing to persist without it?