Last month the United Nations Security Council voted on a resolution to reaffirm the commitment of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty to ban the use or deployment of nuclear weapons in outer space. The resolution failed after a Russian veto, prompting Western countries to accuse Russia of hiding something. In fact, U.S. intelligence has confirmed that Russia is developing nuclear anti-satellite capabilities capable of creating a massive energy wave that can take out constellations of small satellites. These new discoveries coupled with the use of services like Starlink in the war in Ukraine as well as the growing rivalries over space mining force us to confront the future militarized space. Is there a way to prevent this outcome? What’s the best way forward when it comes to space weapons?

For many, keeping outer space from becoming weaponized remains the moral ideal. The development of intercontinental ballistic missiles in the 1950s and the risks of keeping nuclear weapons in space led to the development of the Outer Space Treaty. Weapons of mass destruction were prohibited, and it was declared that space exploration would be done for the benefit of all countries as outer space is “the province of all mankind.” But while we’ve proclaimed that the Moon and celestial bodies shall only be used for peaceful purposes, we have not banned all weapons in space.

There are obvious reasons to promote a ban on the use of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction in outer space, and these reasons have not changed significantly from what they were in the 1950s. Besides the desire to avoid nuclear devastation and destruction to the environment, having weapons of mass destruction in space could undermine international stability and lead to an arms race. There are, however, even more specific reasons to be concerned about the use of any kind of weapon in space today. The first reason concerns the value of satellites for military and economic purposes. The Global Positioning System operates over 30 satellites, with the GPS Block III satellites being the latest deployed. A study by RTI International estimates that a loss of GPS alone would cost the U.S. economy 1 billion dollars per day.

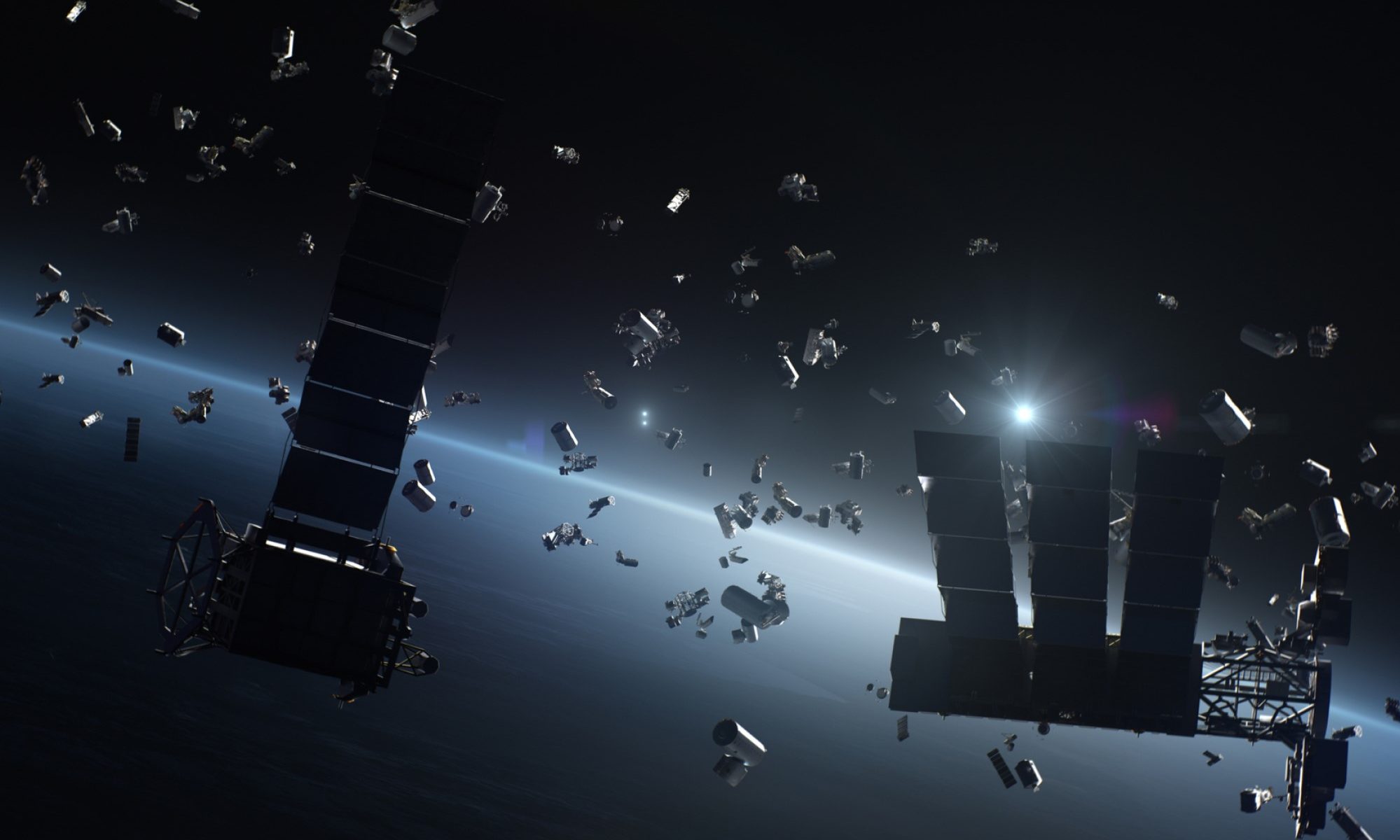

The major ethical risk involved with the use of such weapons, besides the economic and social harms that would follow from the denial of space services, would be that kinetic weapons used in space to destroy satellites would create a “devastating” debris field that “could linger for generations in this unique region of space and interfere with safe operation of satellites.” Once space debris is created, it is almost impossible to control, meaning that other satellites and space stations will be at risk. The debris can continue to move at great velocity through space, posing great danger to other satellites as well as space stations. This can contribute to the possibility of the “Kessler syndrome” whereby debris collisions cascade and lead to more collisions. The use of weapons threatens to exacerbate a problem that already exists and render low-Earth orbit unusable for generations. This can act as a disincentive to use weapons in space because of the risk of mutually assured destruction of the orbital environment around Earth.

To many, the risk of mutually assured destruction may be reason enough to avoid the use of ASATs. However, given the risks involved, not only to both sides of a dispute in space but to all other humans that depend on the space services, this is a problematic ethical response. Despite the risks, it is still quite possible that a country will be tempted to use weapons in space that could soon escalate into full-scale attacks.

But this point may be moot; the weaponization of space may be inevitable. Currently, the United States, Russia, China, and India have demonstrated anti-satellite capabilities. In 2023 Israel intercepted a ballistic missile in space, making it the first example of combat in outer space. The use of missiles to deliver a kinetic payload and destroy a satellite is one possibility, however cyberwarfare, jamming, the use of lasers and other directed-energy weapons to disable a satellite are other possible weapons. For example, a laser-based weapon deployed on Earth could be used to damage the solar arrays of a satellite and deprive it of power, or cyber attacks could allow a satellite to be commandeered. Recently, alarm has been raised by the Chinese Shijian satellite which contains a grappler arm which could be used as a weapon against other satellites.

A second significant reason why nations may be incentivized to use weapons in space would be to protect mining equipment or space stations. Given the plans of the Artemis mission and longer-term plans for mining, a new space race for resources is set to begin. Without a clear framework to recognize ownership (the Outer Space Treaty prohibits any nation from claiming sovereignty over space or a celestial body) there may quickly be competing claims about who is entitled to mine what where. It’s far from obvious how we will settle disagreements about what should be extracted and what should be preserved. Mining operations will not take place without significant investment, and there will be a desire to protect those investments should another state choose to interfere.

If the weaponization of space is indeed inevitable, then perhaps the most prudent step is to attempt to prevent what has already transpired by eliminating all weapons in space as was proposed in 2014. But banning all weapons in space will be problematic if a ban is instituted but bad-faith actors choose to ignore such bans. It may be that the strongest incentive to get such actors to avoid using weapons in space is to offer a deterrence in the form of the destruction of their satellites. Mutually assured destruction could still be useful, if the destruction can be confined to combatants without space debris ruining the orbital environment for the rest of humanity.

Or perhaps we should attempt to regulate the specific kinds of weapons permitted in space. Non-kinetic weapons that do not deliver a payload to eliminate a target such as cyber-warfare, the use of focused-energy weapons, or even potentially grappler arms, could allow nations to respond to perceived satellite threats without being forced to outright destroy a satellite and send its debris across Earth’s orbit. If such weapons are cheaper, easier to use, and more precise than banned weapon such as ballistic missiles or nuclear weapons, this may act as a stronger deterrent in the long run to use such weapons that can affect humanity beyond the combatants involved. This could preserve low-Earth orbit if a conflict does break out.

Given that it is still relatively early days as far as space exploration is concerned, the kinds of conflicting tendencies that might incentivize war may be relatively unknown. Some precautionary principle might help us anticipate and prevent fallout. However, regulation might also be a move that only serves to make space exploration more fraught as nations seek to militarize in secret.