What is at stake in this generation’s Supreme Court? In light of the wave of impactful conservative decisions this year and a Congress embattled over the future of the Court’s composition and political leanings, the highest judicial body of the country has moved to the center of a broader political crisis and partisan divisiveness. Echoing Hamlet, something is “out of joint” in the structure of American politics. But to what extent has the Supreme Court been a sufficient and reliable joint of our democracy? Appreciating the situation of the Court requires considering both its origin as an institution and the partisan context in which it has, contrary to the vision of its architects, become entangled and politicized.

The question of the political nature of the Court has intensified of late partly due to a series of recent judicial decisions that divide along party lines: upholding executive bans on racially profiled immigration, (provisionally) vindicating the right of commercial groups to discriminatorily select their customer base, and declaring that public sector workers cannot be required to pay for collective bargaining with government employers. Social-liberalism must certainly reckon with these decisions from below, both legally and culturally, on behalf of the rights and liberties guaranteed by the Constitution and our obligations to international human rights statutes. There is a broader way of summarizing our situation via the Court and as a society: are we most protected by a court whose majorities adjudicate on principle or one that bases decisions according to political agendas? If the former, we should reflect on the principles by which the Court does or should judge. If the latter, we should rethink the role, existence, and coming-to-be of a Court whose origin James Madison once hailed as a “important and novel experiment in politics” and whose function Alexander Hamilton praised as “the citadel of the public justice and the public security.”

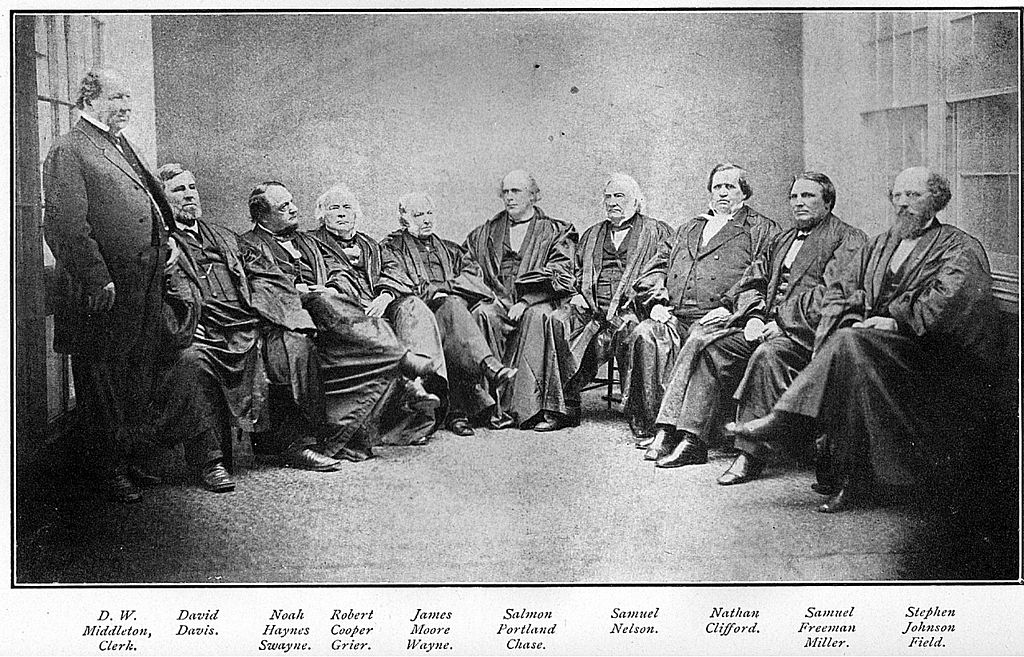

Debates and concerns surrounding the Supreme Court of the United States are neither new nor inconsequential. The Constitution itself outlines few and relatively open strictures to guide the make-up and operation of its highest federal court. Its current state (the number of justices, the scope of its judgment) has thus varied and been determined by legislative decisions, debates, and legal precedents throughout history. Given its evolution, the judicial body has had significant say in landmark decisions, hailed diversely as advancing progress and justifying the country’s worst moral atrocities. The same institution (albeit in different Courts) overturned its previous vindication of racial segregation (Brown v. Board of Education 1954) less than a century after ruling that African-American slaves were property and not citizens (Dred Scott v. Sandford 1857). The recent Trump v. Hawaii decision upheld the right of the President to deny specific ethnic groups entry on security grounds while also overruling the Courts’ past decision to intern Japanese citizens on the same justification (Korematsu v. United States 1944). History changes, and with it the appointed interpreters of its legal and social fabric who are themselves human products of their time and place. But to what extent is partisanship an essential and unavoidable feature of a court system that was originally intended to be a neutral, apolitical “bulwark” against the interests and fluctuations of political ideologies?

The arguments of Federalist Papers No. 78 are clear on the two-fold purpose of the Supreme Court: providing a final “interpretative” appraisal of the legality of all legislative acts according to the Constitution, and a stability in the conditional, lifelong tenure of the judges against the swaying political prerogatives of governing institutions. In short, for Hamilton, the Court should be an antidote to the partisanship of Congress. Its judgment should function as a check on the “force and will” of changing legislative bodies, and thus a source of principled decision against the caprices of the public and the partisan usurpation of public interest. Since the Constitution represents the inviolable rights of the “people,” the Court serves as the “intermediary” between the people and those who claim to govern them. It is a legal body, not a political one. It judges and interprets, and it neither rules nor should be ruled.

The language of disease evoked by Hamilton is neither arbitrary nor simply rhetorical, since the founders understood their novel project to be a complex and vital organism that would not function perfectly and which needed internal therapeutics. “This independence of the judges,” Hamilton argued, is necessary to “guard the Constitution and the rights of individuals from the effects of those ills humors [that] sometimes disseminate among the people themselves, and which … have a tendency … to occasion dangerous innovations in the government, and serious oppression of the minor party in the community.” For Hamilton, there will inevitably be times when elected representatives, an ideologically feverish electorate, or the sway of private interest groups produce oppressive, damaging, or unconstitutional laws. The advantage of a Supreme Court is thus the protection of both minoritarian and majoritarian rights under the Constitution. Without judicial independence, the best feature of democratic worlds becomes the death of democracy itself: “liberty can have nothing to fear from the judicatory alone, but would have everything to fear from its union with either of the other departments.” Fearing the reprisal from partisan constituencies, current members of both parties in the Senate now weigh whether to vote in line with President Trump’s nominee. This fear of the partisan merger of the three branches is our current reality.

In 2017, with the support of a united Republican Congress, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell spearheaded a successful effort to indefinitely postpone a Senate vote on then sitting President Barack Obama’s constitutional right to nominate a Supreme Court Justice. Through changes to Senate rules, this effort countered decades of relatively fair bi-partisan consideration of nominees in favor of a partisan obstruction of any oppositional nomination. In lieu of an upcoming election year, the Senators’ argument was that the voters should ultimately decide on who should appoint such a prominent and lengthy position. Critics will note the equivalence here in Justice Kennedy’s retirement three months before midterm elections which may turn control over the Senate. But for many, these exceptional situations only highlight the intense politicization of the Court’s appointment process. During McConnell’s effort, a Quinnipiac poll found that 68% of people polled thought that “the process of confirming Supreme Court justices has become too partisan,” while only 22% regarded it as “not partisan enough” or the “right amount.”

This is not a new concern. In 1881, Senator John T. Morgan, himself concerned with the disadvantage of Southern States in federal representation following the Civil War, noted that since the Courts’ birth “rival political parties … began to claim it as a right, and to urge it as a party duty, to put judges on the bench who were decided, able, and zealous in their support of party measures and party declarations of political principles. It would be very difficult, in recent times, to a cite a single exception to this rule.” Morgan continues: “To place the federal judiciary entirely under the control of one political party is an almost irrevocable step in the direction of absolute government.” Perhaps now we can say that to leave the Court in the hands of the party system would be to acquiesce to an oligarchic system of power that has long governed us.

Critics will argue that the political appointment of justices, whose tenures span over different legislative regimes, does not entail that they will necessarily vote along party lines or with political motives. Furthermore, focusing on partisan voting in the Court ignores the fact that the majority of its decisions are not split along these lines (though it has increasingly done so). These considerations, however, are dampened by the fact that the nomination process has now become an explicit political weapon in an open partisan war. Ethically, our situation is one of envisioning measures that, as the founders of the Constitution themselves intended, could mitigate the encroachment of the legislature on the judiciary. These range from the extremes of abolishing the Court itself to amending the power of appointment in favor or either “assisted appointments” or the direct democratic elections of Justices.

There are practical challenges to all these measures, but perhaps their arguments hinge on whether the American people want a say in the people and principles that judge them. If they do, then it is important to remember that the Constitution is changeable by design. Thomas Jefferson once criticized the idea of a Constitution that would be “too sacred to be touched” and a mentality of his generation that only the founders would have the right to, as Thomas Paine eloquently described their power, “begin the world over again.” The history of Amendments are one instance of an augmented political system, and the spirit of the Supreme Court itself another. As Hannah Arendt notes in On Revolution, the special authority of the Court’s interpretative power is “exerted in a kind of continuous constitution-making” (Penguin, 2006, 192). Crises and prolonged stalemates are, if anything, opportunities to return to the drawing board.

The American political system is a holistic structure, and the problems of the Court are not isolated. When treating a disease, practitioners know that addressing the symptom is inadequate. If the disease of partisanship has spread to those organs with the power to regulate it, then looking to the source of the party-system might be medically advisable for the sake of the health of the body politic.