Few slogans are as rhetorically powerful as “my body, my choice.” It captures a fundamental intuition: that individuals should have control over what happens to their own bodies. People rightly recoil at the idea of being forcibly subjected to another’s will, and the phrase is often invoked to argue for bodily autonomy in areas like abortion and end-of-life decisions. The assumption is that, as long as an individual’s actions do not harm others, they should be free to do as they please with their own bodies.

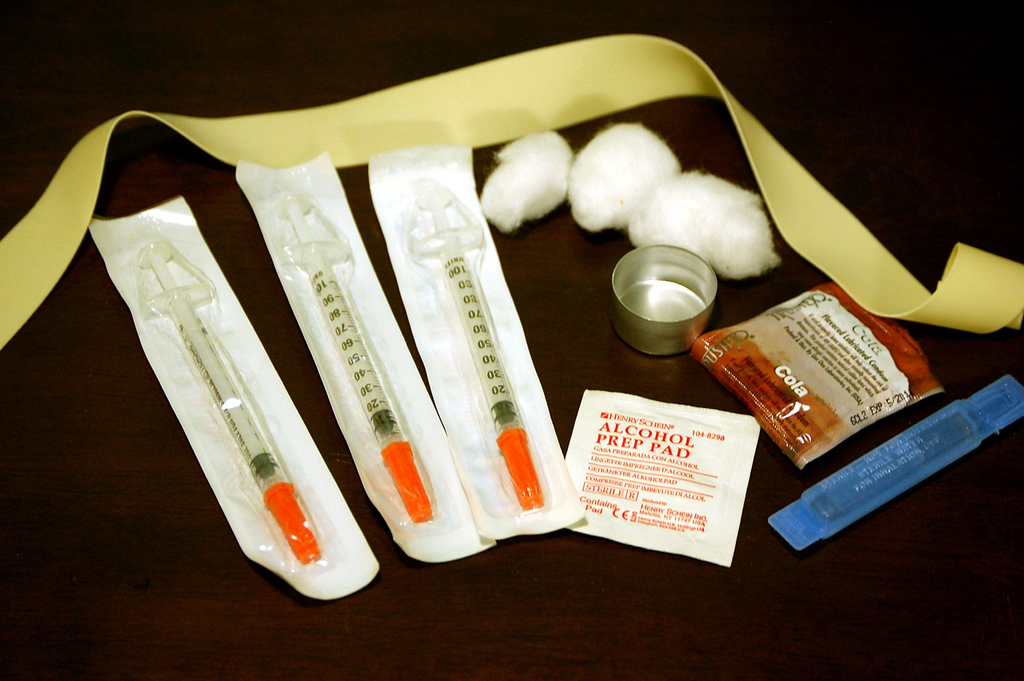

Given this, some argue that drug legalization naturally follows from the “my body, my choice” principle. If a person wants to engage in the recreational use of drugs, the reasoning goes, that is his decision alone. As long as he does not harm anyone else, the state has no business interfering. The case seems simple enough — until we examine it more carefully.

The problem is that freedom is not just about making choices; it is about making choices rationally. True autonomy is not simply the absence of external interference but the ability to govern oneself through reason. A person who deliberately impairs his rational faculties through recreational drug use is not exercising freedom. He is attacking it.

To be clear, I am not making the case for any particular drug policy. My point is simply that we need to be honest about what drugs do and not dress up something destructive to freedom in the language of liberty, even if restrictive drug laws are ultimately unjustified.

Freedom Requires Rational Self-Governance

The conceptual justification behind the “my body, my choice” argument assumes that individuals possess and retain rational self-control over their decisions. However, the problem with recreational drug use is that it directly undermines this ability.

Mind-altering substances do not just create pleasurable experiences, they chemically alter the brain in ways that impair self-governance. Recreational drug use can distort judgment, suppress self-restraint, and, in many cases, create dependency that weakens one’s ability to make future choices freely. A person under the influence of drugs is not acting as a fully rational self-governing agent but as someone whose thoughts and actions are being heavily influenced by an external chemical influence.

This is true whether the drug in question is alcohol, marijuana, psychedelics, or harder narcotics. Even substances that supposedly “enhance” mental function (such as certain stimulants) often do so at the cost of rational self-regulation, increasing impulsivity and distorting judgment. When we speak of drugs altering rational agency, we are not only referring to substances that depress cognitive function but also to those that overstimulate it. Proper cognitive function depends on homeostasis, a balanced and well-ordered state that allows the mind to perceive reality clearly and process information accurately. The purpose of our rational and cognitive faculties is to enable us to (1) perceive reality accurately so that we can (2) deliberate soundly so as to (3) act in accordance with the truth. All of these functions are distorted by recreational drug use.

If freedom is about self-rule, then a person who deliberately places himself in a state where his ability to rule himself is severely diminished is not exercising freedom. Invoking drug use as an exercise of freedom makes as much sense as touting the benefits of drinking seawater as a remedy for thirst.

This is not abstract philosophical theorizing. The law already recognizes that a person who is mentally incapacitated cannot validly consent to certain decisions. Contracts signed under severe intoxication can be voided. A person high on drugs cannot give legally binding consent to medical procedures. The state intervenes when individuals threaten suicide by placing them in involuntary psychiatric holds. Why? Because we recognize that rational self-governance is a necessary precondition for meaningful autonomy.

How Drug Use Turns You Into a Slave

The defining feature of slavery is the absence of self-governance. A slave does not act according to his own rational will but is controlled by an external force that dictates his actions. The master determines what he does, where he goes, and how he lives. That is precisely what happens when someone consumes a substance that then overrides their rational faculties. While physical slavery is imposed by another person, chemical slavery is self-imposed. For both, the end result is the same: a loss of autonomy.

A person under the influence of drugs is no longer fully acting according to rational self-direction. His will is hijacked by a foreign chemical influence that suppresses judgment, distorts perception, and overrides impulse control. At that moment, he is not truly free. His actions are dictated by the effects of the substance rather than by reasoned deliberation.

This is not a metaphor. A person in the grip of a mind-altering substance literally loses self-mastery, even if it is just temporarily. The person who becomes addicted to drugs does not simply choose to continue using; his ability to choose is progressively eroded as the drug rewires his brain and makes rational self-control more difficult. At that point, he is no longer the master of his actions — the drug is his master.

John Stuart Mill, who first articulated the “harm principle,” recognized the problem posed by enslaving oneself. In On Liberty, Mill wrote that “The principle of freedom cannot require that [one] should be free not to be free.” In other words, freedom does not include the right to permanently destroy one’s own ability to be free. A person who permanently sells himself into slavery is not exercising freedom but abolishing it. The same logic applies to someone who places himself under the control of a substance that strips away his ability for self-rule. A person who willingly puts himself under the influence of something that systematically erodes rational control is doing the opposite of exercising freedom. Although Mill was talking about political slavery, his points apply just as equally to chemical slavery.

The Paradox of “My Body, My Choice”

The deeper irony of the “my body, my choice” argument is that the more a person engages in self-destructive drug use, the less able he is to make meaningful choices at all. A person addicted to meth, heroin, or even high-potency marijuana is not exercising greater autonomy; he is increasingly at the mercy of chemical dependency, impaired judgment, and distorted perception. His decisions are no longer fully his own. Instead, they are shaped and dictated by the drug.

If we reject political slavery because it violates autonomy, then we should likewise reject chemical slavery, because it produces the very same result: a person who is ruled by something other than his own rational will. A society that tolerates and normalizes widespread chemical enslavement is not a society that is maximizing freedom.

What About Alcohol?

Even alcohol is not immune from this critique. Alcohol, like any substance that affects the mind, can be used in ways that compromise rational self-governance. A person who drinks to the point of intoxication is, in that moment, undermining his own ability to think clearly and act rationally. A blackout drunk, a reckless binge drinker, or a person who routinely drinks to escape reality is no different, in principle, from the drug user who deliberately seeks intoxication. The problem arises when consumption crosses the line from responsible use to rational impairment.

However, the key difference between alcohol and hard drugs is that alcohol can be used in moderation without necessarily leading to impairment. A person can have a glass of wine with dinner, a beer at a social gathering, or a whiskey while unwinding after a long day without losing rational control. Unlike recreational drugs, which are taken precisely for their intoxicating effects, alcohol is unique in that it allows for consumption without cognitive dysfunction.

This is why alcohol is tolerated in a way that drugs like cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, or hallucinogens are not. There is no responsible way to use these substances recreationally — their entire purpose in being used is to override rational agency. Unlike alcohol, which can be incorporated into normal life without necessitating impairment, the defining feature of recreational drug use is that impairment is the goal.

That said, alcohol abuse is clearly subject to the same concerns as other forms of intoxication. Alcohol, like any substance that affects the mind, can become a means of self-imposed enslavement when it is used to evade reason rather than complement normal, responsible living.

So while moderate alcohol consumption does not necessarily violate the principles of rational self-governance, its misuse certainly can. The fact that alcohol allows for some responsible use does not mean it is exempt from the general principle that true freedom requires rational control.

Freedom Requires More Than Just Choice

Recreational drug use is incompatible with freedom. The more a society tolerates and encourages such behavior, the less free that society becomes, not because the government is restricting choice, but because its citizens are actively degrading the very faculties necessary for responsible self-rule.

So does “my body, my choice” work as a defense of recreational drug use? No. It is logically incoherent and self-defeating. If we care about autonomy, we should reject the idea that freedom includes the right to systematically destroy the very conditions that make freedom possible.

Whatever we think about drug legalization, we should at least be honest about what drugs do. Freedom is not a magic word that turns self-destruction into autonomy.