Recently, I discussed the potential consequentialist justifications for Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s new bill reintroducing the death penalty for those who commit sexual battery on a child under the age of 12. I argued that, for the most part, these justifications seemed lacking. It’s important to note, however, that there are a number of other ways in which we might justify punishment. In this article, I want to consider an alternative approach: namely that of retributivism.

While consequentialism looks forwards to the potential goods that can be achieved by punishment, retributivism instead looks backwards for its justification. According to the retributivist, the necessary harm of punishment is justified purely on the basis that the offender committed a crime – regardless of what future goods may (or may not) be achieved by this punishment.

There are many cases in which consequentialism and retributivism will disagree on whether punishment is justified. Imagine a case where a community passes a new law forbidding skateboarding in its downtown pedestrian mall. While this law is welcomed by the community at large, it is met with vehement opposition by a small minority. One of this group decides to openly break the law, skateboarding through the mall in protest. This hooligan is apprehended, and the judge must now decide whether or not to punish him. Suppose, however, that punishing this particular hooligan will serve only to foment further dissent and encourage even more cases of skateboarding protests.

The consequentialist justifies punishment on the basis of its deterrent effect – that is, its ability to deter future instances of crime (committed by both the offender and the wider community). In this case, then, the consequentialist will seemingly be forced to concede that punishing the hooligan is not justified. The retributivist, on the other hand, will disagree. Since retributivism is backwards-looking – paying no mind to the consequences of the punishment, and instead focusing solely on the fact that the offender committed a crime – it will still hold that punishment of the hooligan is justified.

It’s worth considering, however, precisely what it is about committing a crime that makes it justifiable to punish an offender. One common way of doing this is to claim that by committing a crime, an offender forfeits certain rights. Why? Well, we might argue that my possession of a right necessarily entails a duty to respect that right in others. Thus, when I violate the right/s of another, I forfeit my own corresponding right/s. We can call this Forfeiture-Based Retributivism.

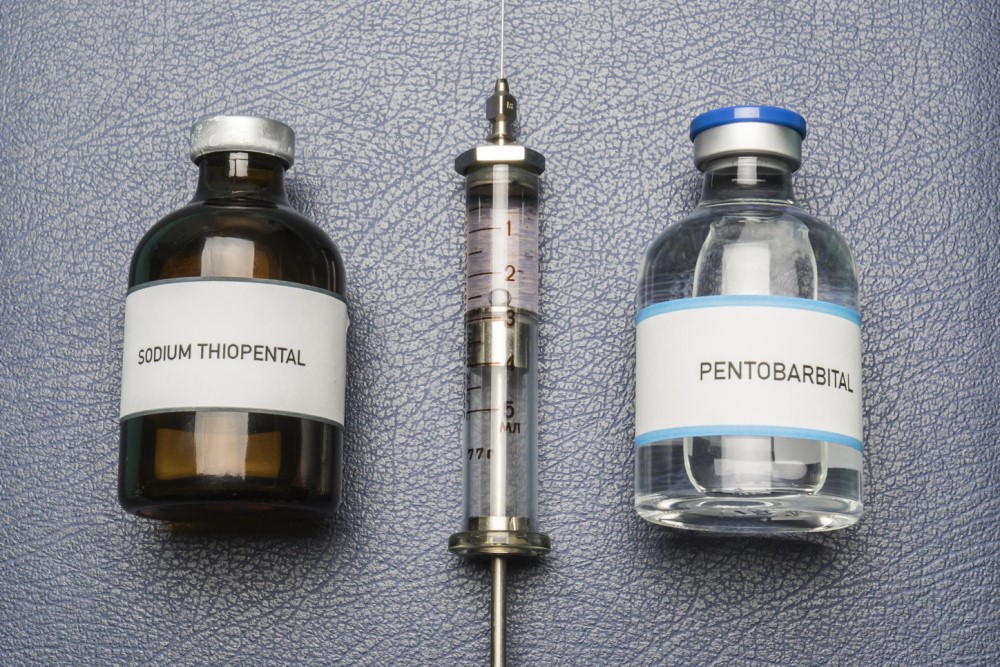

There are many cases where Forfeiture-Based Retributivism provides a straightforward justification for a case of punishment. Consider, for example, the death penalty as a punishment for murder: My possession of the right to life entails a corresponding duty to respect your right to life. Thus, when I violate this right (i.e., by committing a murder) I simultaneously forfeit my own right to life, and in doing so empower the state to intervene and execute me for this crime.

It’s an intuitive approach – and one that underpins many discussions of how we treat offenders. It is, however, deeply problematic. If the right we violate dictates the right we forfeit, then this will lead to all sorts of strange conclusions regarding the punishments that the state is justified in administering. Consider the skateboarding example above. The hooligan has clearly violated their duty to not skateboard in a pedestrian area. According to the Forfeiture-Based Retributivist, this would entail the hooligan losing their corresponding right. But it’s unclear precisely what that right would be. A right to not have others skateboard in their area?

In other cases, the punishments endorsed by Forfeiture-Based Retributivism move from the absurd to the unacceptable. Consider the crime here under discussion: sexual battery on a child. In committing this crime, an offender violates their victim’s right to bodily autonomy in the most reprehensible way imaginable. According to Forfeiture-Based Retributivism, this offender would subsequently forfeit their own right to not have their bodily autonomy violated in this very same way. Put simply: Forfeiture-Based Retributivism seems to suggest that the perpetrator of sexual assault should be punished by also being sexually assaulted.

Some might find this an acceptable outcome. But most will not. While we might wish to see such offenders punished severely, we will most likely stop short of endorsing that rapists ought to be raped in retribution. This, however, seems to be precisely what Forfeiture-Based Retributivism entails.

An alternative way of providing a retributivist justification might be to simply claim that an offender simply deserves to be punished. We can call this Desert-Based Retributivism. The notion of desert should be a familiar concept for most. Basically, it boils down to the idea that good actions should receive good consequences, while bad actions should receive bad consequences. Suppose that one of my students writes an exceptional essay, while another plagiarizes an incredibly poor essay. The former, it seems deserves a good grade, while the latter deserves a bad grade. Why? This is harder to explain, but it seems to be rooted in the fact that the state of affairs in which the good student receives a good grade is better than the state of affairs in which they don’t. Likewise, the state of affairs in which the bad student receives a bad grade is better than the state of affairs in which they don’t.

Can Desert-Based Retributivism provide a justification for sentencing child sex offenders to death? Possibly. But while it might be clear that the abhorrent actions of these offenders deserve bad consequences, Desert-Based Retributivism fails to provide a specific answer to just how bad those consequences should be. Are they deserving of the most serious punishment at our disposal? This remains unclear. But there’s also a deeper problem with Desert-Based Retributivism: namely, that it justifies punishing the innocent. There are many people who deserve bad consequences despite having broken no law. Consider the vile racist, or the unrepentant philanderer. Racism and infidelity are not crimes, but these individuals clearly seem to deserve punishment for their actions. Should the state, then, punish these individuals, despite the fact that they are (legally) innocent? If we think not, then it seems we might have to look elsewhere for a potential justification for punishment.

While punishment is something we often accept without question, its justification requires careful consideration. This is particularly true where the punishment involves ending a human life. While few would argue that those who commit sexual battery on a child should receive punishment, a reasoned justification for the severity of this punishment is much more difficult to provide. Perhaps we think that child sex abusers should receive our most severe penalty for reasons of deterrence – but this approach is fraught with complications. We might, on the other hand, think that these offenders have forfeited certain rights, or simply deserve to be punished as severely as possible – but problems arise here too. Ultimately, this means that our discussion of the severity of punishment appropriate for child sex abusers needs to be carefully carried out on the basis of reason, not emotion. It’s unclear that the legislative procedure behind Florida’s new law followed any such process.