“Hear me clearly: America is not a racist nation.” So declared Senator Tim Scott in his address last month. Refusing to acknowledge a messy explanation of how institutional racism contributes to significant racial disparities in criminal justice, healthcare, education, and economic outcomes, Scott chose the tidier, more familiar framing of racism as an all-or-nothing character trait. As though racism must always take the form of a conscious and deliberate act. As though offenders must have violence on their mind and evil in their hearts. As though longstanding inequities could be the simple work of a few bad apples.

But Scott’s pronouncement wasn’t designed for nuance, it was meant to serve a particular political function: contesting the need for race-based education in our schools.

“A hundred years ago, kids in classrooms were taught the color of their skin was their most important characteristic. And if they looked a certain way, they were inferior. Today, kids again are being taught that the color of their skin defines them, and if they look a certain way, they’re an oppressor.”

Race-based education, Scott claims, is infected with the very same racial essentialism it seeks to expunge. Whatever their intentions, these educational programs are thought to be reductive — they reduce individuality and personal responsibility to a matter of skin color and treat race as though it were the only relevant characteristic defining one’s social identity. But, as Scott argued, “It’s backwards to fight discrimination with different types of discrimination.” As such, race-based education stands accused of being divisive. By focusing exclusively on our differences, it pits us against each other rather than bringing us together. Perhaps most damning of all, race-based education challenges an article of faith: that the social, political, and economic rewards reaped in this life are proportional to the sweat of one’s brow.

These charges, however, misunderstand (and sometimes willfully misconstrue) the purpose and aims of race-based education. Critical race theory, the unnamed villain in Scott’s address, is designed to question the ways we perceive our society and the ways we are perceived. These reflections provide us the opportunity to develop and strengthen our racial and social literacy. At its very core, critical race theory challenges each of us to appreciate our situatedness (or perhaps “thrownness”). There is no view from nowhere; we all speak from a specific perspective informed by a unique lived experience, and we each possess a particular point of view. If we are to truly come together and bridge that gap, then we must learn to recognize these differences and begin to develop a shared language with which to communicate — identifying the barriers to the inclusive and just society we wish to share, as well as articulating the work needed to dismantle them.

Critics often assert that critical race theory is not a proper pedagogical model because it focuses on what to learn rather than how to learn. In truth, however, it offers us an alternative lens by which to gain perspective on our social situation and consider the ways things could be otherwise. In this way, critical race theory delivers real educational goods: the civilizing of students, the enlargement of imagination and empathy, the cultivation of rich and meaningful autonomy, and the development of independent judgment by challenging dogmatic ways of thinking and perceiving.

The political war being waged on race-based education is not new. Senator Scott’s statements echo Trump’s proclamations that critical race theory represents “radical indoctrination,” and Scott’s words speak in support of Trump’s (since rescinded) ban on the “un-American propaganda” in diversity and inclusion initiatives. Critical race theory is smeared as left-wing proselytizing, the toxic by-product of the Great Awokening spilling out of the ivory tower and threatening education reform from grade school on up. To escape being swallowed up by PC culture and white guilt, there is but one recourse: Resist. And many conservative state legislatures are responding by outlawing any and all attempts to broach the subject of slavery and segregation in American history in the classroom.

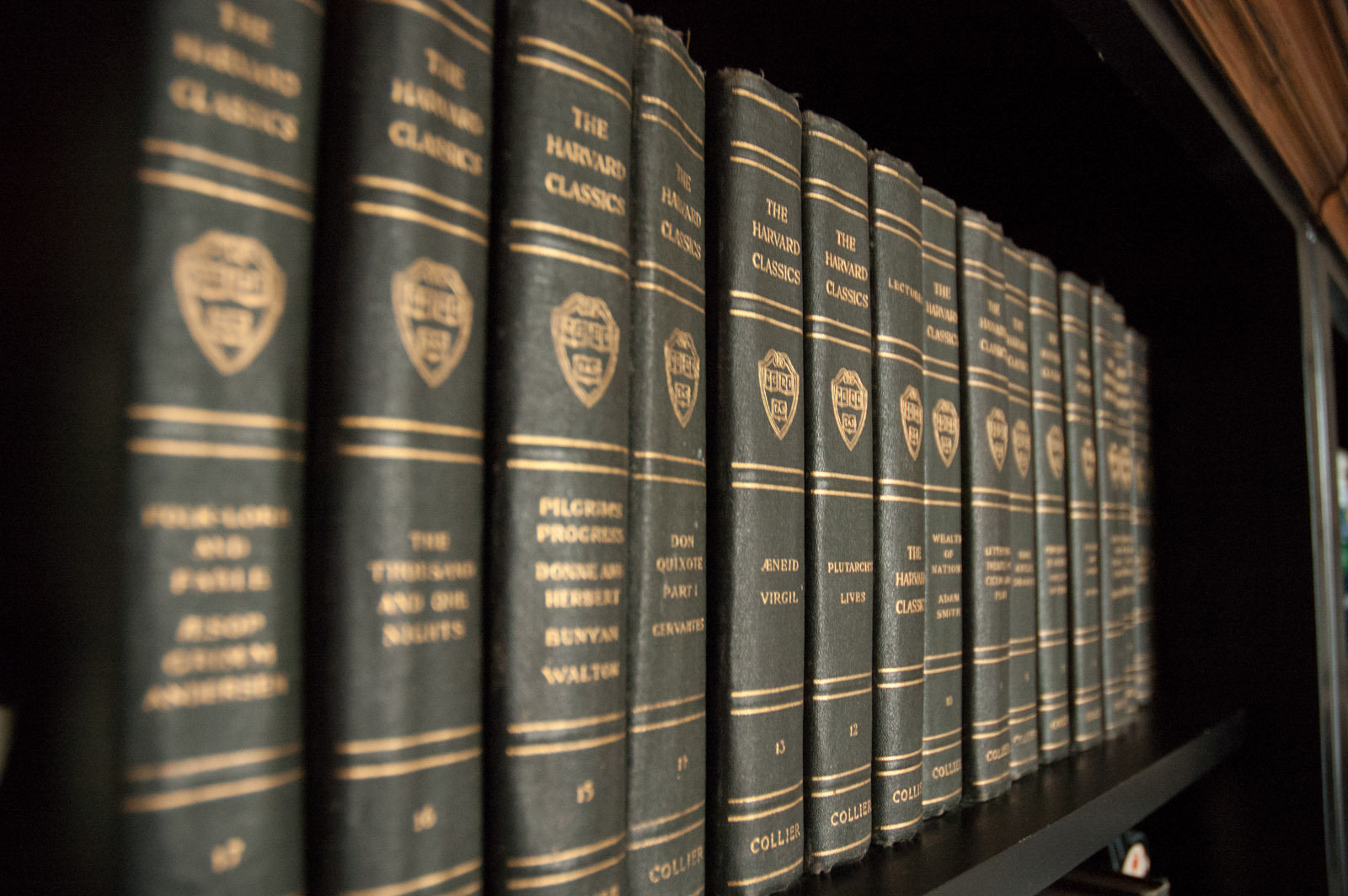

In the wake of recent events, many schools have been prompted to reconsider their traditional course offerings. Unfortunately, proposed changes to the education curriculum are continually cast as a struggle over the soul of the nation. Just last month, Cornel West and Jeremy Tate referred to Howard University’s dissolving of its classics department as a “spiritual catastrophe,” signaling the “spiritual decay, moral decline and a deep intellectual narrowness run amok in American culture.” Contrary to faculty’s explanation, they depict Howard’s decision as a loss of faith. Lacking the strength of conviction to defend the sacred texts, Howard succumbed to pressure from the woke mob. The barbarians are at the gates.

In defending the discipline from would-be reformers, West and Tate emphasize the formative power the study has for its disciples. “Engaging with the classics and with our civilizational heritage” they argue, “is the means to finding our true voice. It is how we become our full selves, spiritually free and morally great.” But the idea that one must assimilate oneself into Western culture in order to find one’s true identity and have anything meaningful to say is precisely the problem. It may very well be true that only through understanding our place in history can we ever hope to know ourselves, but the question that remains is: whose history?

This question is especially pressing for a discipline like classics. Even scholars within the field are beginning to question the ways in which the study lends itself to supporting white supremacy narratives, promotes Eurocentrism, and is instrumental to the construction of whiteness. As classics professor Dan-el Padilla Peralta has argued, “the production of whiteness turns on closer examination to reside in the very marrows of classics.” So how might we separate the meat from the bone and dismantle the power structures that seem inextricably fused to the life-blood of the discipline?

This discussion regarding what should be excised and what can be rescued within the classics curriculum reflects the substantial difficulty facing us in the larger societal conversation. Unfortunately, these questions are often explored in terms of who is cancelling whom — is the left out to expel all conservatives from the academy, or is the right suppressing academic freedom by claiming that all education is merely liberal ideology? But this way of assessing the debate only encourages us to retreat to our separate political corners. Commentary devolves into scorekeeping: whose tribe is winning? At present, public debate is paralyzed, consumed in accusing the other side of one of two untenable extremes: continuing to actively ignore an oppressive status quo, or burning everything to the ground.