Paying significantly more money for a product based almost exclusively upon its pink color seems ridiculous. However, many women are unaware that they are doing exactly that on their weekly trips to the grocery store. In fact, the physical separation of men’s and women’s products in many stores often prevents both sexes from ever noticing the price difference between products. Awareness of the “pink tax” and the ethical debate associated with gender-based pricing has risen significantly in recent years. In fact, both New York and California have made gender-based pricing against the law and many consumers are calling for more states to do the same.

In order to grasp just how widespread and significant this issue is becoming a study was published in New York City called “From Cradle to Crane: The cost of being a female consumer”, which was research conducted to encourage government action. The study, as referenced on an NPR broadcast, illustrated that on average women are paying 7-8 percent more than what men were paying for comparable products in departments such as clothing. However, personal care products are the items most notorious for blatant price discrepancies, being on average 13 percent more expensive for women across a variety of products including deodorant, shampoo, shaving cream, and particularly razors.

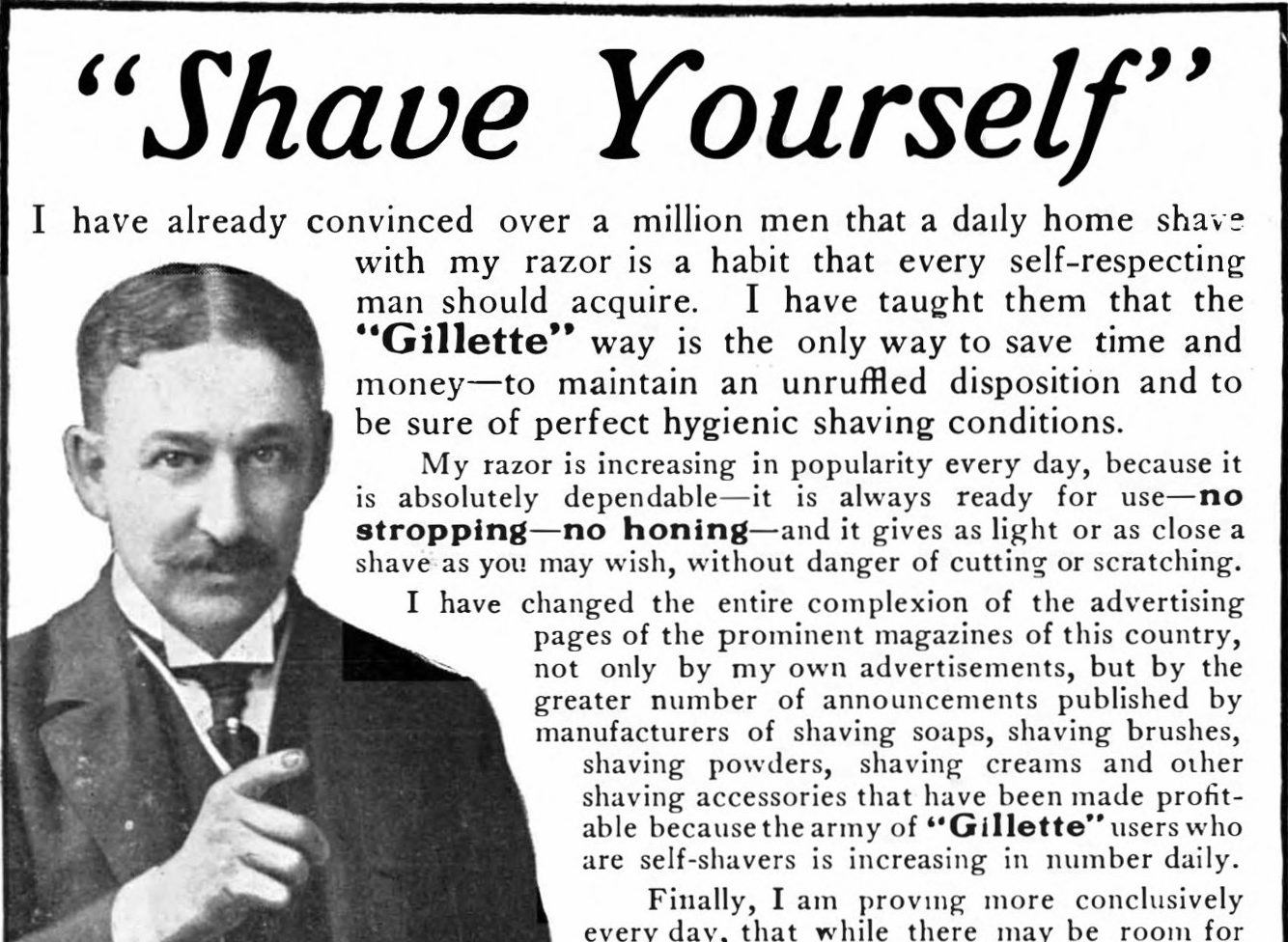

In fact, many news outlets including NPR, NBC, and CNN have investigated these price differences at drugstores and grocery stores across the country to understand how this discrimination plays into female consumers’ everyday lives. Karen Duffin from NPR went to a Walgreens in Times Square and found one packet of the same basic razors from the women’s section and the other from the men’s. The brand and quantity for both packets remained the same, however, the men’s razors were priced at 59.9 cents per razor, whereas the same razors for women were doubled at $1.25 per razor. Also, price differences are not exclusive to retailers. Investigative reporting on The Today Show actually depicted gender-based pricing in services such as dry cleaning as well. A male and female reporter both bought the same white button-down shirt from the same department store in men’s and women’s aisles and took them to a dry cleaning store. The male reporter’s total bill totaled only $2.50 while the female reporter’s bill totaled $5.00. When asked about the price difference, the manager explained that the machines used to press the shirts were only made in sizes suitable for men’s clothing, women’s smaller shirts are unable to fit in these machines and thus must be hand-pressed. This difference in pricing between genders introduces the ethical issue of why services such as dry cleaning are designed for male consumers while not acknowledging the needs of female consumers. In other words, why can we not begin to standardize these sorts of businesses so that one sex is not charged more for the same service than the other.

Although a few dollars here and there may not seem like a significant issue for female consumers, these slight differences in pricing for comparable products result in women paying an annual “gender tax” of approximately $1,351 extra annually compared to men, according to the Study of Gender Pricing in NYC. The difficulty in addressing this issue, however, is because it is difficult to determine exactly where in the supply chain the price hikes are added to feminized products, as trade lawyer Michael Cone explains to CNN Money. Cone is convinced that price gouging is occurring on women’s products. The study elaborates on the example of women’s shirts:

“[S]hirts with buttons on the right side (for men)…were taxed a couple percentage points less than shirts with buttons on the left side (for women). He brought both examples to the federal court claiming that US import tariffs discriminate based on gender, however both of his claims were dismissed.” (Sebastian, 2016)

Higher taxes on women’s products, (for example, shoes: the tax on men’s shoes is set at 8.5 percent whereas women shoes are taxed 10 percent) have been under research for over 15 years. The United States is also not the only country becoming increasingly aware of the implications associated with gender-based pricing. In Britain, the issue has been brought to Parliament as women “could be paying up to twice as much as men for what appeared to be identical products” (Sebastian, 2016).

Another important ethical question is if perhaps these price differences are not discrimination at all, and are simply due to legitimate contrast in the ingredients and formulas between men’s and women’s products. However, the New York City study brings up a counterargument that these higher prices are difficult for women to avoid and that “individual consumers do not have control over the textiles or ingredients used in the products marketed towards them, and must make purchasing choices based only upon what is available in the marketplace.” As a result the choices made by marketers and manufacturers place a substantially higher financial burden upon female consumers in comparison to males.

This discrimination deserves more media attention, which is why many of these studies are becoming a call to action for women to become aware of price discrimination in products they buy. This awareness also has the potential to encourage women to compare products marketed to either men or women in a variety of categories, and base their product choices upon unit price instead of merely packaging. Eventually, if women begin utilizing this knowledge to put pressure on companies, more state governments would be willing to introduce a ban on gender-based pricing. In the meantime, it may be worth walking a few aisles further and picking up that blue razor.