This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

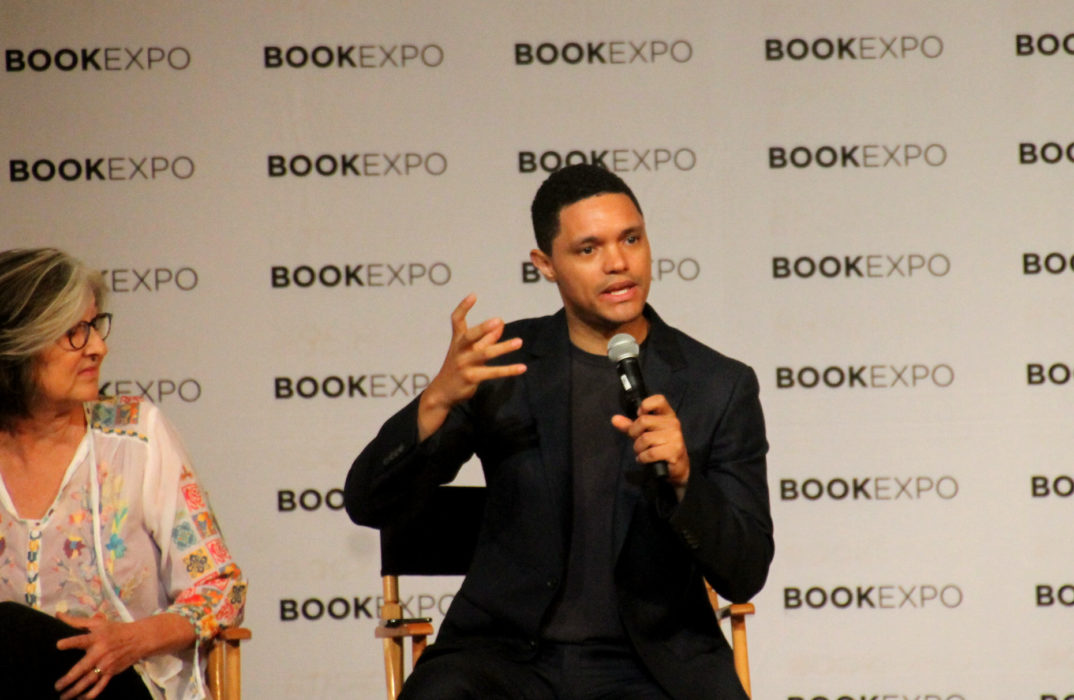

In celebration of France’s World Cup win, Trevor Noah congratulated Africa and the Africans on their victory. This was a commentary on the majority of France’s players having African heritage, but was quickly met with a response from the French ambassador.

The question of French identity has often been controversial, and in a letter to Noah, the French ambassador points out that when xenophobic neo-Nazis spread their hateful messages, they use rhetoric similar to Noah’s – emphasizing the “Africanness” of some citizens of France, which for the neo-Nazis speaks against their French identities.

The French Ambassador to the United States, Gerard Araud, was speaking for the “colorblindness” ethos that is alive and well in France today, largely a response to its troubles with rampant xenophobia. France recently removed “race” from its constitution in a move to further the value of viewing the world through a “colorblind”, or race-free, lens and instead see the human race, and especially the French people, as unified.

Noah pushed back against the idea that someone’s origins did not matter. In his original segment, he joked, “You don’t get that tan in the south of France”, and in his response to the ambassador’s letter, he alluded to the colonial history that underpins the immigration story for so many of France’s African heritage citizens. These presses fit with the Comedy Central host’s overall call for more nuance and context, both in discourse and dialectic (when he uses his culture’s slang it means something different than when a hateful white person does) and in our understanding of identities (having one heritage does not necessarily make you have less of another – being African should not preclude Frenchness).

In drawing attention to this latter point, Noah noted in particular the passage where Araud claimed, “Unlike in the United States of America, France does not refer to its citizens based on their race, religion or origin. To us there is no hyphenated identity. By calling them African, it seems you are denying their Frenchness.” In avoiding emphasizing hyphenated identity, France attempts to emphasize a national unity and undermine the divisive xenophobic influences. After all, in 1998 when a diverse French team won the World Cup, a political leader condemned the team’s ability to represent France on the basis of their heritage, claiming they were unworthy and didn’t know the words to the national anthem.

However, in battling the ambassador’s supposed message of unity, Noah paints the US’s hyphenated identity as a positive alternative, as though France’s criticisms were wholly unfounded. There are worries with the “colorblind”, race-denying, and ahistorical approach to governing and understanding a nation such as France is attempting, perhaps, but in a call for more nuance and context, Noah celebrated the United States’s inclusion of hyphenated identities as though it has been a road towards inclusion and celebration of heritage here historically.

In his remarks about the issues with France’s value of colorblindness, Noah points out that in practice it often amounts to a selective colorblindness, where someone’s non-French origins are noted when their non-desirability is at stake. When someone wins the World Cup, they’re French, but when you’d rather not identify them as a part of your nation, they’re “from elsewhere”. This is typically how hyphenated identities work in general, including in the US.

In her recent comedy special Nanette, Hannah Gadsby discusses identity at length. She addresses straight white men in their current time of discomfort in a telling way: this is the first time their identity gets a name. Previously they’ve been “human neutral”. Typically, you get a hyphen for being different, marginalized, some identity that gets dealt with. This point is consistent with Noah’s point about how the French identity is granted as an honorific often in discourse. And with a hyphenated identity comes a label to celebrate and feel pride, overcoming marginalization in community and strength; as Noah notes, there are parades for some, like Saint Patrick’s Day.

It is important that one identity isn’t denied by noting another. One person can be a member of multiple communities. However, having a country of hyphenated identities does not solve the problems of racism and bigotry any more than taking race out of a constitution and aiming for “colorblindness.” It’s more nuanced than that.