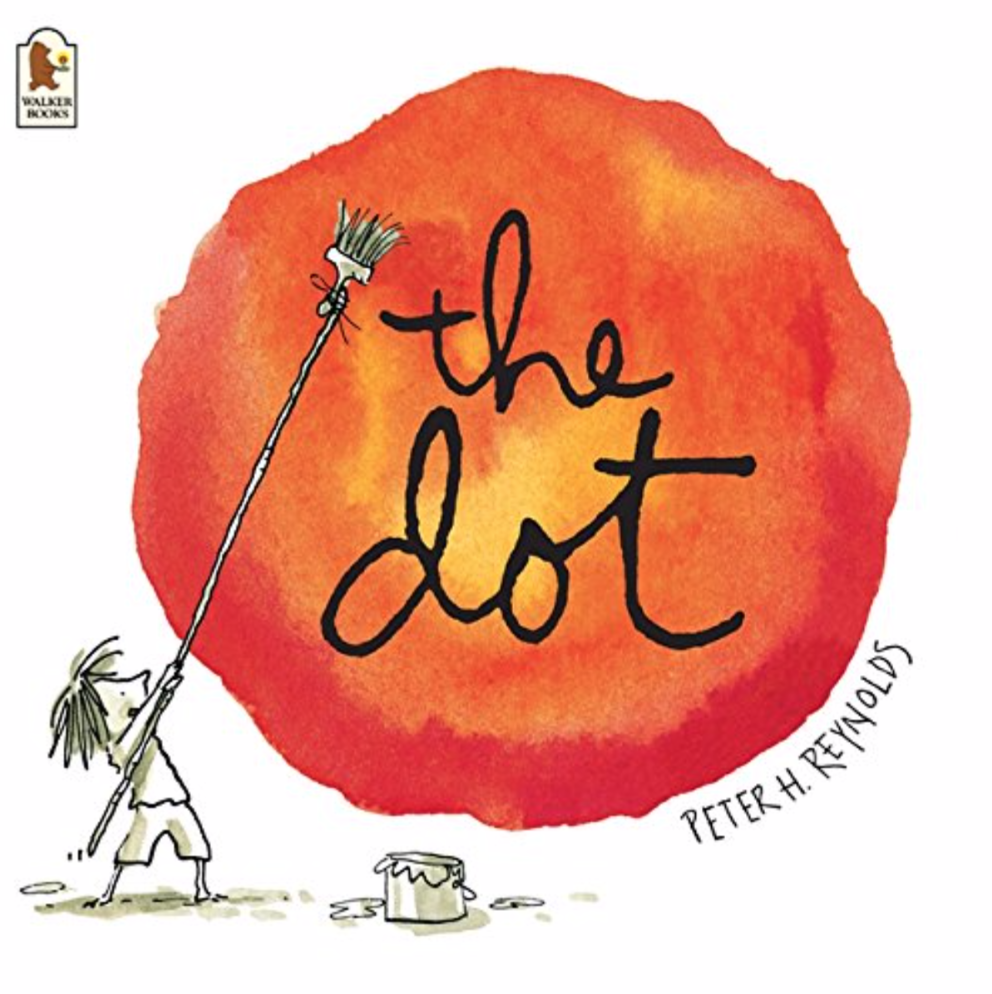

The Dot

Book Module Navigation

Summary

The Dot is about aesthetics and asks two central questions: “What is art?” and “What makes art good?”

In art class, Vashti convinces herself that she can’t draw. Her teacher encourages her to “make a mark and see where it takes you.” Vashti makes a frustrated mark on the page, and her teacher asks her to sign it and displays it for everyone to see. Realizing she can draw a better dot, Vashti begins creating many more dots. Vashti meets a little boy in awe of her work. The boy is convinced that he can’t draw. Vashti encourages the boy to “make a mark and see where it takes you,” which sets in motion a whole new story.

Read aloud video by Peter Reynolds

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

The Dot raises philosophical questions about the definition and evaluation of art. The questions can be accompanied by the following activity.

One way to begin the lesson is with a hands-on activity before reading. For this activity, each student has a blank piece of paper and a marker in front of them. Each student is asked to make a single mark on their paper. The activity is a fun way to engage and learn kinesthetically, and is also a good jumping off point for later discussion. Once the children have completed the activity, have them put their papers aside to listen to the story. While you will refer back to this activity in this module, it isn’t needed to have a philosophical discussion.

Vashti simply marks her paper with a dot. She doesn’t think of this ‘painting’ as art until her teacher asks her to sign it, and then proceeds to hang it up. The question arises: Is Vashti’s dot painting art? Discussion can begin with this question. If children say “yes”, you can ask: What about the dot makes it art? If children say “no”, you can ask: Why not? If a child offers a definition of art, ask the other children if they can think of a counterexample. If they cannot, bring one up yourself, and ask if they think it’s art. For example, if a child thinks the dot is not art because it is not representative of anything, give an example of an abstract work of art.

One option at this point in the conversation is to bring in different candidate pieces of art which kids might disagree about. For example, you could show abstract art, sculptures, or photographs. For each candidate piece of art, ask the kids whether they think it is art or not, and why they think so.

One definition of art that some philosophers have suggested is an institutional definition of art. The basic idea is this: Something is art (a) if it is meant to be a contribution to the art institution, or (b) if the art institution has deemed it art. For example, the fact that some artifact is in an art museum could be the reason why it is art. Alternatively, an artist might want something to be considered art by art-appreciators and other artists, so since it was created with this intent, it is automatically art. Something like this is going on in The Dot. Did the dot painting become art once it was framed and hung up on the wall (i.e. put into an institutional context)? Or did the dot painting become art when Vashti signed it (i.e. submitted it to others as something that is art)? Attention can be brought back to the dots that the children drew. Ask: Are the marks that you made art? Would they be art if you hung them around the room or put them in a museum? What if they signed them?

The Dot also raises question about the evaluation of art. Maybe Vashti’s dots are art, but are they good art? You can start this discussion by asking the kids: What’s your favorite type of art? Follow this with: Why do you like it? Use their descriptor words to ask a generalizing question about all art. For example, if a child describes their favorite piece of art as beautiful, ask the other children if they think all good pieces of art need to be beautiful. This may also lead to a conversation about immoral art. If someone depicts something unpleasant, such as a cat on fire, is it a bad piece of art?

When giving these examples, ask children whether they like or dislike a couple of the pieces. If there is a disagreement, this gives the opportunity to ask the question: If someone likes a piece of art, and you don’t like the same piece of art, how do we know if it is good art or not? Does one of us have to be right and the other wrong?

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

What is Art

- Is Vashti’s first picture art? Why or why not? What makes it art?

- Did signing it make it art? If so, what if she never signed it?

- Does hanging it up make it art? What about in a museum? If so, what if she never hung up the dot; would it no longer be art?

- Would it have been art if she signed the blank paper (without a dot)?

- Does someone have to decide that something is art for it to be art? If so, who decides whether something is or is not art?

- Does all art have something in common? If so, what might this be?

- Does art have to represent something?

- Does art have to express something?

- Does art have to be human-made?

- If I think something is art and you think it isn’t art, is one of us right and one of us wrong?

Evaluating Art

- What makes something good art?

- Does art need to be hard to draw or make?

- Does art need to be creative or unique?

- Does art need to be beautiful? What makes art beautiful?

- Does art need to make you feel a certain way when you look at it?

- Can art be wrong or immoral? What if someone draws a picture of a cat that’s on fire–is there something bad about that?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Sarah Magid and Daniel Gorter. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.