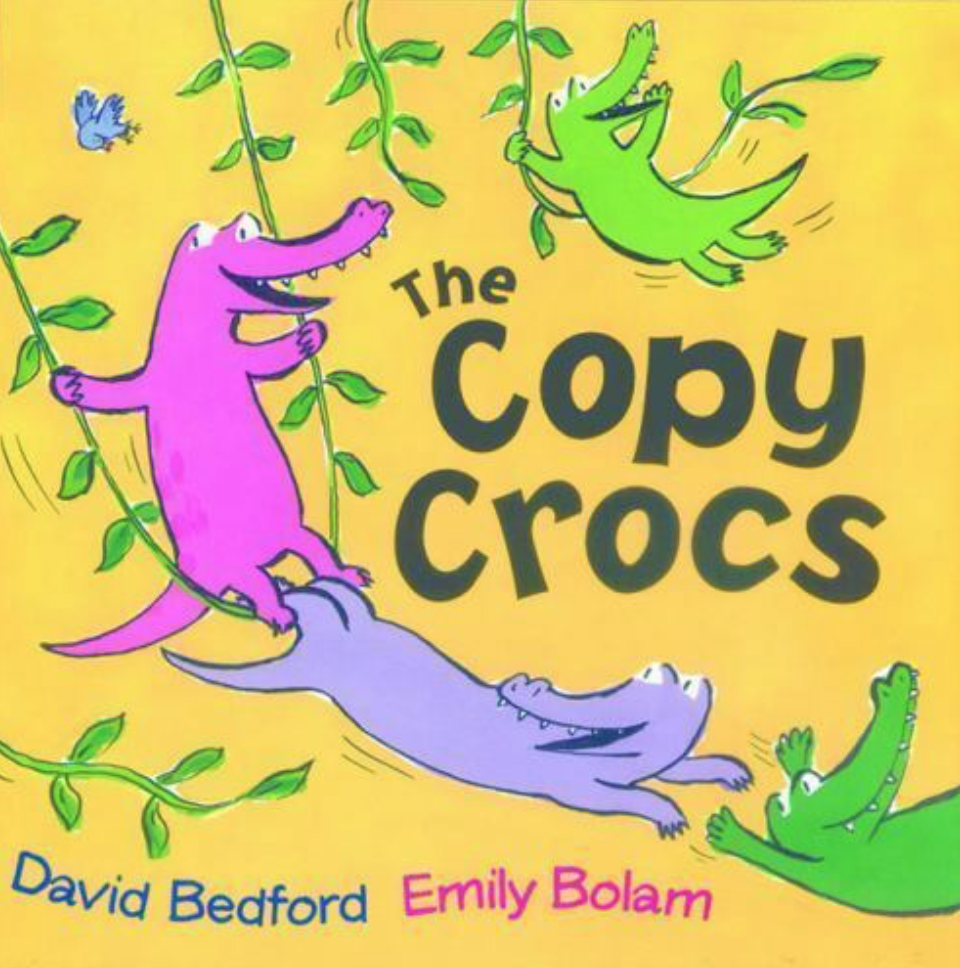

The Copy Crocs

Book Module Navigation

Summary

The Copy Crocs considers questions about the ethics of “copying,” the nature of property, and what makes a good life.

When Crocodile gets tired of sharing a crowded pool with all the other crocs, he ventures out to discover new places to hang out. Each time he finds a place that he enjoys, the other crocs — the “copy crocs” — quickly join him in his new stomping ground, much to Crocodile’s chagrin. Will Crocodile ever learn to share?

Read aloud video by CWA School. The read aloud ends at 4:18 and the video ends with an art lesson based on the book .

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

We’ve all heard the old platitude, “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.” However, when we take a closer look at copying behavior, we discover that there are a number of philosophical questions underlying every “copycat” incident. For instance, most of us would not condemn me for copying a friend’s outfit, hairstyle, or hangout spot. But when imitation took the form of copying a friend’s academic work, why would it be inappropriate, even morally reprehensible? In either case, I would be taking my friend’s idea, or what may more formally be considered my friend’s intellectual property. In the academic realm, utilizing another’s intellectual property is acceptable, so long as we give the source adequate credit. Is this also true in copy crocs’ case? That is, is copying someone else’s behavior without acknowledging that it is theirs in some way as blameworthy as using someone else’s academic writing without a proper citation?

One might respond by appealing to a difference in consequences. In terms of consequences, it’s just not that big of a deal to copy someone’s clothes or where they like to hang out. It just makes that style or place more popular, and maybe the person who found it slightly annoyed. This is unlike the case of academic work. With academic work, careers and diplomas are at stake. In taking this intuitively appealing approach, we are using a particular philosophical framework for making normative judgments: consequentialism. Loosely, a consequentialist posits that whether an act is morally right or wrong should be determined by the consequences of that act.

The other crocs in this story inspire us to think not only about intellectual property but also about property more generally. They matter-of-factly tell Crocodile that the pool is not his pool and that the mountain is not his mountain. What does make something yours? What makes something your private property? We often think that if something is your private property, you have special, if not exclusive, access to it. How do we justify these special rights? Many philosophers have tackled this question. John Locke posited that you make previously unclaimed land and natural resources yours, your private property, when you “mix” your labor with it. So, if you pick an orange, that orange is yours because you made an effort to pick it; you mixed your labor with it. This view, though intuitively appealing, certainly has puzzling elements. How exactly do we define the outcome of mixing your labor with something ? When you picked the orange, did that particular orange become your property, or did the whole tree become your property? This is not to mention that Locke’s theory does not clearly apply to cases where the entity in question is already privately owned.

Throughout the story, Crocodile also realizes that he likes exploring on his own as well as spending time with the other crocs. He comes to the conclusion that the good life for him is balanced. Aristotle thought that reaching eudaimonia, loosely translated as “happiness,” is the ultimate end for a human being. In order to reach eudaimonia, one must become a person of practical wisdom. The behavior of a person of practical wisdom always consists as a mean between two extremes, and this mean is fitting to his circumstances. In a dangerous situation, a man of practical wisdom would determine how to take action in a way that fits between the extremes of being cowardly and being reckless—he would be courageous. In this story, Crocodile finds the proper mean between being entirely solitary and overly social.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Imitation

Crocodile shouts at the other crocs, “Stop copying me!”

- Have you ever copied someone else? Why did you copy them?

- Has anyone ever copied you? What did they copy? Did that annoy you? Why or why not?

- Do you think that copying Crocodile’s hangout places (e.g., the muddy pool, the river, the mountain) is different from copying Crocodile’s spelling test? What makes them similar or different?

- Is copying someone’s idea the same thing as stealing someone’s idea? What makes them similar? What makes them different?

- Do the other crocs give Crocodile any credit for finding the new places to hang out? What if they said that they had found the cool places to hang out? Would that be wrong or unfair? Why or why not?

Consequentialism

Crocodile asks, “Why do you keep copying me?” The other crocs respond, “Because you’re always doing new, fun things.”

- Why do the other crocs copy Crocodile?

- Are the other crocs doing something wrong when they copy Crocodile? Why or why not?

- Does anything bad happen to Crocodile when the other crocs copy him?

- What if the other crocs copied Crocodile’s spelling test? Would anything bad happen to Crocodile then?

- Is what happens to Crocodile when the other crocs copy his hangout place worse than what would happen to Crocodile if the other crocs copied his spelling test? Why or why not?

- Which is worse, copying someone’s hangout place or copying someone’s spelling test? Why?

Property

The other crocs tell Crocodile, “We can sit here if we want. It’s not YOUR mountain.”

- Do you think the mountain is Crocodile’s mountain? Do you think it belongs only to Crocodile? Why or why not?

- Do you have anything that belongs only to you and not to anyone else?

- Why does it belong only to you and not anyone else?

- Do you like having things that belong only to you? Why or why not?

- If something belongs only to you, should other people be allowed to use it? Why or why not?

- If something belongs only to you, should you have to share it? Why or why not?

- What if something used to belong to your friend, and then your friend gave it to you? Can it still belong only to you?

- Can something belong to a lot of people all at the same time? Or does it have to belong only to one person?

Relativism

Crocodile “never knew his pool was so big” until he was the only one in it, until it was empty. Also, Crocodile thought there was only room for one at the top of the mountain, but he finds out later that all of the crocs fit on the mountain.

- Are you big? Why do you think you are or aren’t?

- Can you just say that you are big or small? Or do you have to say that you are bigger or smaller than something else?

- Crocodile “never knew that his pool was so big” until it was empty. Was the pool always big, or is it only big because Crocodile is alone in the pool?

- Can something be big, but you don’t realize that it is big?

- Can we just say that something is good or bad? Or do we have to say it is better or worse than something else?

The Good Life

When the other crocs surprised him, “Crocodile felt wonderful.”

- Do you like to spend time by yourself?

- Do you like to spend time with other people?

- Which do you like better, spending time by yourself or spending time with other people?

- Are there certain times when you would rather be by yourself? Are there certain times when you would rather be with other people?

- Is it a good thing to be by yourself all the time? Why or why not?

- Is it a good thing to be with other people all the time? Why or why not?

- Do you like doing new things, things that you’ve never done before?

- What is something that you have done a lot of times?

- Which is better, doing new things, or doing things that you have a lot of times? Why?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Allison Drutchas. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.