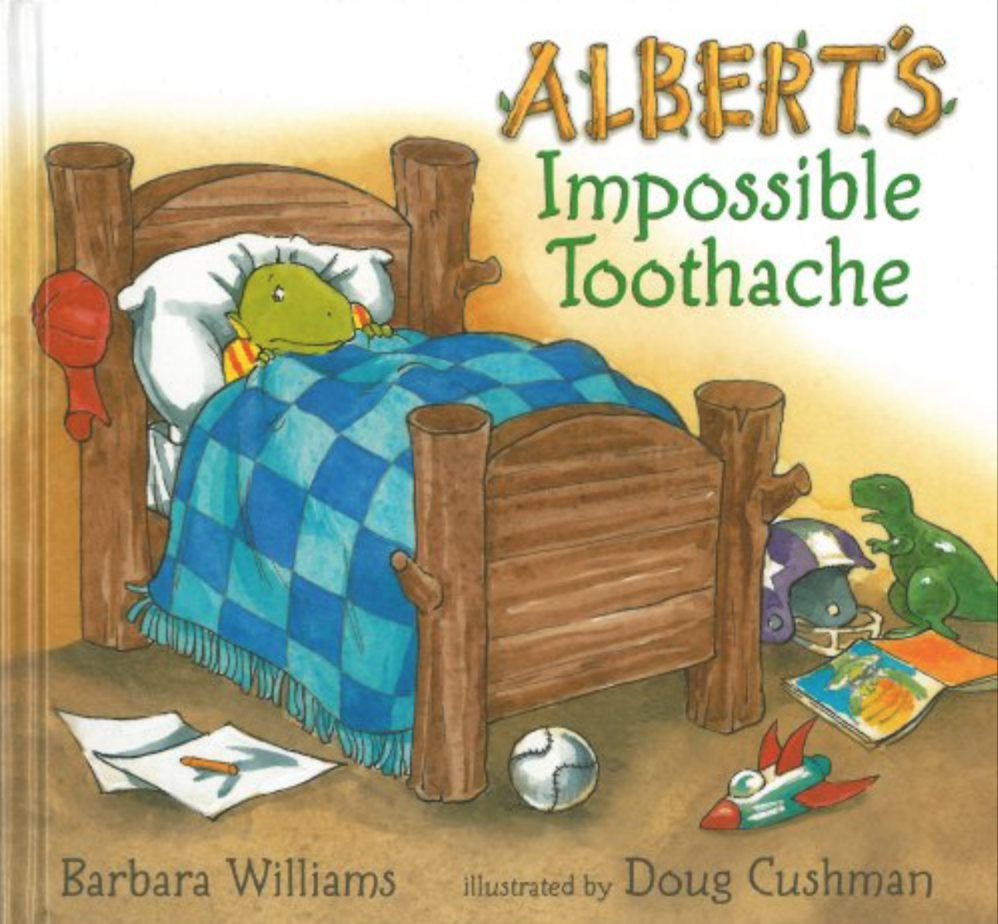

Albert’s Impossible Toothache

Book Module Navigation

Summary

How can you have a toothache without a tooth? How do we prove whether the impossible exists?

Little Albert Turtle’s parents are worried about him. He won’t get out of bed because he claims he suffers from a toothache, in spite of the fact that turtles don’t have teeth. Does Albert really have a toothache? If he does, will anyone ever believe him?

Read aloud video by Ms. CeCe (no ads)

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

Albert’s Impossible Toothache raises a cluster of issues relating to metaphysics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. Albert the turtle tells his father that he has a toothache. But his father doesn’t believe him. Albert’s father thinks that because no one in the family has ever had a toothache before, it is impossible that Albert should have one.

But Albert’s father seems mistaken. Just because no turtle in the family has had a toothache before doesn’t mean that it’s impossible. There have been events in history and even in our own lives where we have experienced completely new things, things that have never happened before. In light of Albert’s father’s apparent mistake, we might recognize a philosophical distinction here. On the one hand, things can either be possible or impossible.

On the other hand, things can either exist or be make-believe. Some of the things we imagine are things that do not exist but are still possible. For example, I can imagine that I had painted my bedroom a different color. Other things we believe could never happen. Some philosophers think, for instance, that we can imagine there to be beings physically just like us, but without any sort of mind whatsoever, but no such beings could ever exist.

Returning to Albert’s toothache, it seems what his father meant to say is that Albert’s toothache is imaginary, that Albert does not really have a toothache. The reason is the simple fact that turtles do not have teeth. After all, you need a tooth to have a toothache. So maybe Albert is imagining his pain. Sometimes we imagine things so realistically that our creations can seem real to us. But can we really imagine ourselves into pain? Many philosophers have held that if one thinks she is in pain, then she is, that the feeling of pain is sufficient to demonstrate reality.

Another possibility is that Albert is not imagining his pain, but is mistaken about what kind of pain it is. Perhaps Albert has pain, even though he has no tooth. After all, Albert desperately tries to get his father to believe him by pointing to his mouth to show his father where the toothache is. To be sure, in order to point to a toothache, one must be pointing at a tooth. Thus, yet another interesting philosophical idea that emerges in the story relates to whether pointing at things to refer to them is the same as calling them by name. It seems that we can quickly identify things by pointing at them, but what about when the thing you are pointing to doesn’t exist, like Albert’s toothache?

Another issue has to do with the meaning of the term “toothache.” Maybe that’s why at one point in the story Albert says that a gopher bit him. Perhaps the pain of the gopher bite is what Albert is attempting to refer to. In this case, there are interesting philosophical questions relating to how we attempt to use words and gestures to talk about the world, and to what happens when our interlocutors miss our references. This kind of consideration leaves one wondering whether Albert is actually not making things up but rather failing to identify them correctly, or in a way that makes sense to others.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

The nature of reality

Albert Turtle says he has a toothache. Albert’s father says it is impossible and points to his own toothless mouth.

- Do you need to have a tooth to have a toothache?

- Just because something doesn’t exist, does that mean that it is impossible?

Albert still insists he has a toothache. His father says that Albert’s brother has never had a toothache, that Albert’s sister has never had a toothache, and that Albert’s mother has never had one. “It’s impossible,” Albert’s father says, for anyone in this family to have a toothache.

- If something has never happened before, does that mean it is impossible that it will ever happen?

- Can you think of something that has never happened in the past, but might happen in the future? What?

- Has anything ever happened to you that has never happened to anyone else? What?

- How do you know it has never happened before?

- Can something impossible ever happen?

Possibility and the Imagination

Turtles don’t have teeth, but Albert says he has a toothache.

- Can you imagine something that is “impossible”? What?

- How do you know it is impossible?

- Turtles don’t have teeth, but Albert says he has a toothache. Is Albert just imagining that he has a toothache?

- Is there such a thing as an imaginary ache?

- Do imaginary aches hurt less than “real” ones? Is it possible for imaginary aches to hurt as much as real ones?

The nature of demonstrative action

Albert “points” to his toothache and his father points his own lack of teeth.

- Can you point to something that isn’t there, like no teeth?

- Suppose you ask your friend for a cookie, and she points to the cookie jar. You reach in and are disappointed to find that the jar is empty. Is your friend pointing to something that isn’t there?

- Is pointing to something the same as calling it by its name?

- Are there times when you don’t understand what someone is pointing to? When?

- Are there times when you point to something, and people don’t know what you mean? When?

- Find something in the room and point to it. Now, without moving your finger, try to think of three different things someone might think you are pointing to. What are they?

Albert says the Gopher bit him. Maybe by “toothache,” he meant the Gopher’s teeth and his ache.

- Is it possible that Albert is pointing at a real ache, but not a toothache?

- Can we point to things and talk about them, even if we don’t know what to call them?

- How will we know we are talking about the same thing?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Gareth B. Matthews. Edited May 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.